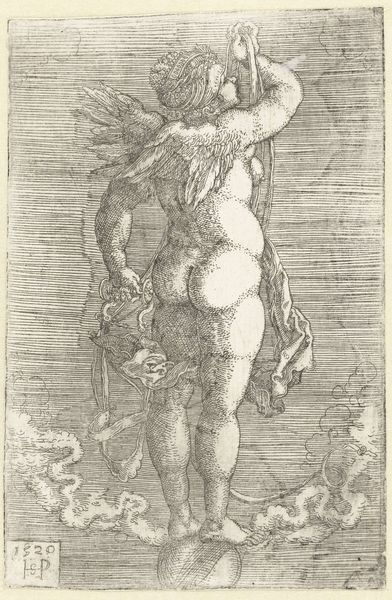

engraving

#

allegory

#

mannerism

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 50 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This engraving, “Venus als Lust,” made around 1600 by Wierix and currently housed in the Rijksmuseum, has a remarkable textural quality despite being an engraving. What’s interesting is seeing not just Venus herself, but this whole bustling landscape of laborers surrounding her. How does the work's material form and process of creation intersect with its subject matter? Curator: Exactly! Forget about the classical mythology for a moment. Look at the lines etched into the copper plate; each one is a physical act, a mark of labor. Wierix was a master engraver, part of a thriving printmaking industry in Antwerp. This wasn’t about individual artistic genius, but skilled craftsmanship reproduced for a market. Consider the societal conditions; the work was made as commodity to meet demands. The figures in the background, blacksmiths, anglers, builders...they're all engaged in productive activities. Does the image create any direct relationship between their labor and Venus’s allure? Editor: I see what you mean. It’s like Wierix is connecting Venus – traditionally a symbol of leisure and beauty – with the world of work, suggesting her desirability fuels industriousness. It’s printed with lines, and we see lines in every task in the background! But doesn’t that almost *elevate* those labors? Is that the artist's intent? Curator: Perhaps not "elevate" in a moral sense, but certainly acknowledge. This era of art and production shows these as interrelated elements, rather than opposing forces. This work is more interesting as artifact of that cultural exchange than as any idealized version of history and mythology, Editor: I never considered how the economic conditions of art creation can inform our understanding of the images depicted! It really changes my perspective. Curator: Absolutely. Examining the materials and the labor involved opens up the layers and implications, helping to re-evaluate the visual culture and industry in 17th-century Antwerp.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.