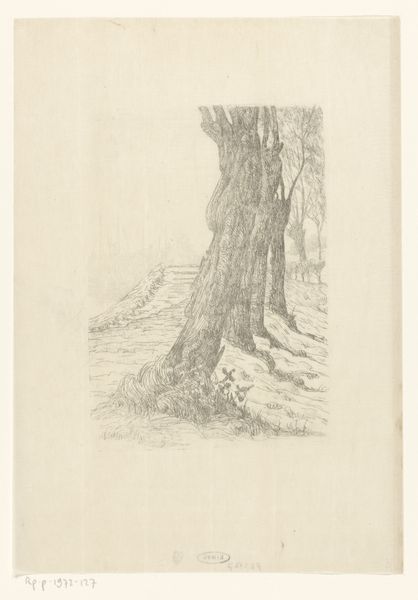

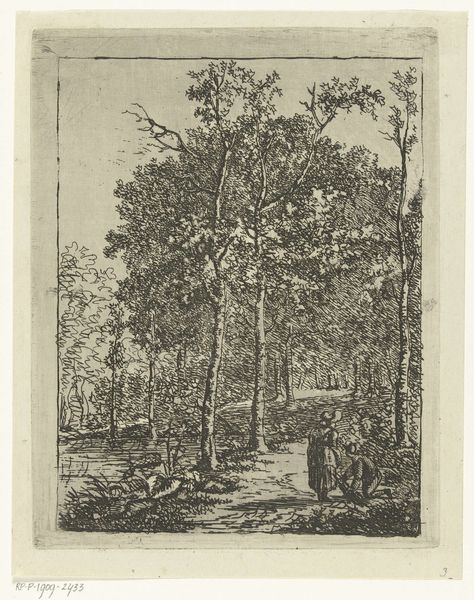

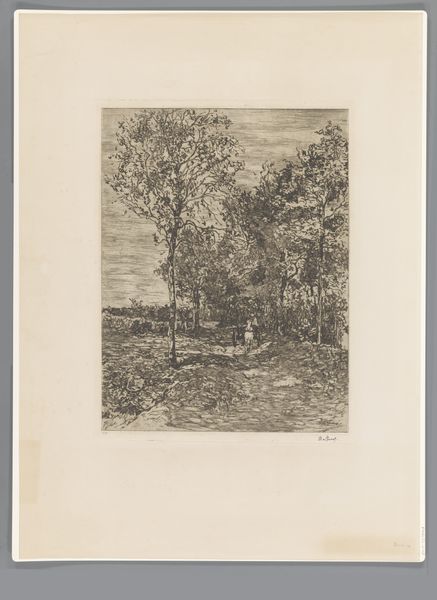

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

realism

#

monochrome

Dimensions: height 490 mm, width 342 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

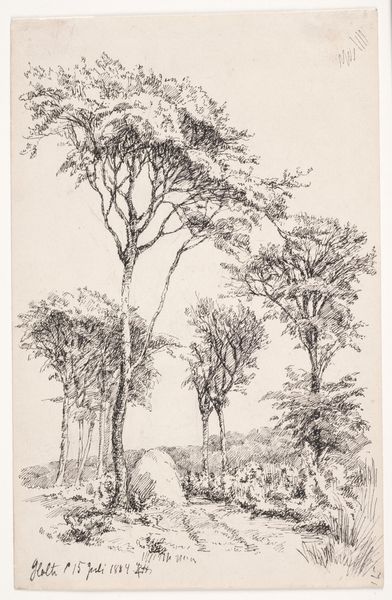

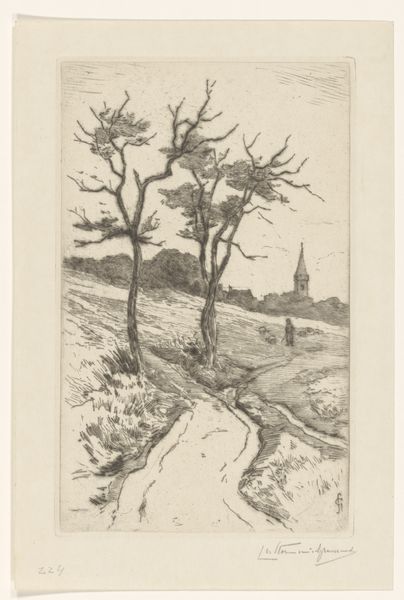

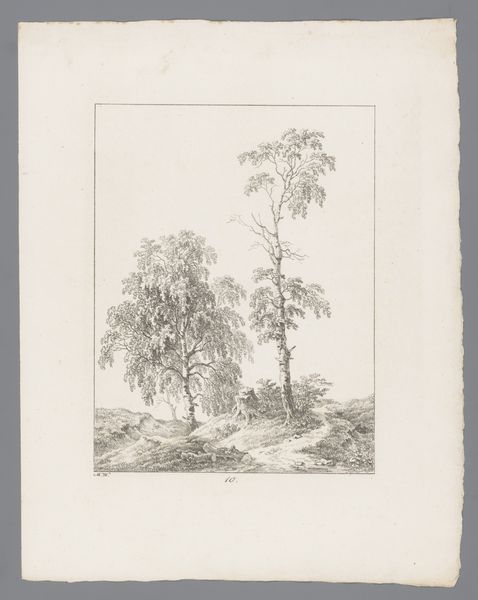

Curator: So evocative...it feels like looking into a memory. Almost a little haunted, perhaps. Editor: We’re looking at "Berken op heuvel", or "Birches on a Hill," an etching by Simon Moulijn, created around 1930, and now residing here at the Rijksmuseum. You know, etching's a printmaking technique using acid to corrode a design into a metal plate. I'm curious about that haunting quality you mention. What brings that out for you? Curator: Well, the monochrome palette lends a starkness, of course. But it's also how the artist renders the background. The other trees are almost like ghosts...or a hazy, retreating crowd, a receding history. And the texture of that lone tree on the hill... it feels like it's aging right before your eyes. Do you feel that, that sense of ephemerality? Editor: Absolutely. The ghostly trees and that wizened birch centralize nature's cycle, reminding me of ecocritical theory’s deconstruction of the nature/culture binary. Simon Moulijn draws birches and the natural environment to symbolize the very real connection between exploitation, nature, and cultural landscapes that is inherently social. He really captures the life of nature here, its rise, its height, its fade, and the material impact it has on all those living with it. Curator: You're right, it isn't just melancholy. It has teeth. Do you think that that idea about how exploitation impacts life in cultural landscapes applies more to landscapes with direct colonialistic ties? The cultural landscape here feels very native. Editor: It's always present, even if veiled. Consider how the aesthetics of landscape art have historically served nationalistic agendas, and how certain landscapes have been prioritized or idealized over others, often to justify territorial claims or erase indigenous presence. But looking specifically at Moulijn here, his intimate focus contrasts sharply with grandiose landscapes often found within nationalistic artworks, challenging ideas about dominant power and control. He sees himself as a steward. It gives him purpose to appreciate this one tree. Curator: Absolutely, it seems like he's encouraging us to consider the local rather than the imperial...to slow down. It all goes back to memory... personal history rather than historical narrative. It is beautiful work, made ever more vital with our perspective. Editor: Precisely! Hopefully our listeners will see more in this than they thought when they happened upon it, seeing this commentary as yet another dimension of this quietly defiant drawing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.