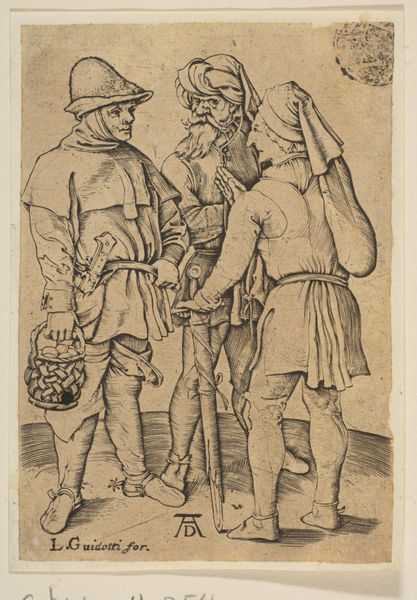

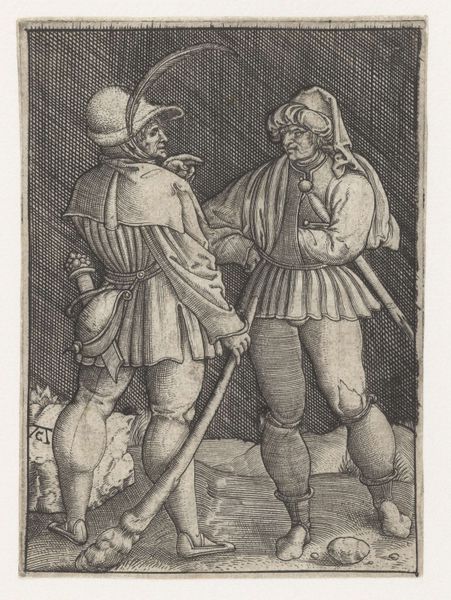

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

Curator: Here we have Albrecht Durer’s engraving, "Three Peasants In Conversation", completed around 1497. The figures dominate the space, don't they? What strikes you immediately about this work? Editor: It's stark. The lines are so precise and unforgiving. It feels heavy, almost claustrophobic despite being three figures on a relatively bare background. Curator: Well, Durer was deeply interested in the everyday lives of people, reflecting in a time of dramatic social upheaval across Europe. He used his art to address questions of value and cultural norms—questions still vital today. These peasants are not romanticized but shown as individuals. How might their depiction play into broader narratives of social class and labor at the time? Editor: The material reality of their lives is laid bare, isn't it? Look at the textures of their clothing. The rough, heavy fabric contrasts starkly with their lean bodies. It reminds you how their labor shaped not only the materials they handled but also their own physicality. Engraving was physically demanding; one can imagine Durer's calloused hands producing this piece reflecting the working class depicted in it. Curator: Absolutely. There's a certain stoicism there, wouldn’t you say? Considering the Northern Renaissance preoccupation with representing humankind and spirituality in ordinary lives, I find it striking how their body language seems weighted with a burden. How can we connect the engraving as an object, in itself industrially-produced, with the reality of the people depicted and the socioeconomic structures Durer wanted to point out? Editor: It makes me think about consumption as well. Engravings like these circulated widely, bringing images of the working class into wealthier homes, becoming almost objects of voyeurism. Think about it: the very act of producing and consuming this kind of image reinforced existing social hierarchies, even if it seemed to offer a realistic and honest view of labor. Curator: That’s a great insight; it truly is a visual commodity within a market reflecting larger questions about power, labor and who gets to tell whose stories. By showing such careful realism of those usually ignored, Durer’s art seems a subversive, politically charged act. What are your final thoughts? Editor: My take is this piece compels us to consider art's uncomfortable position—how artistic endeavors both reflect and construct social divides. And how that dynamic can be deeply rooted in materiality. Curator: And on my end, that by paying close attention to social history and lived experience, an old piece might offer relevant perspectives on how modern identity is constructed. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.