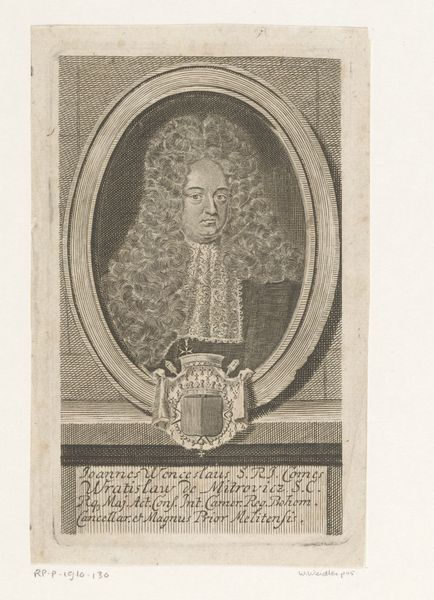

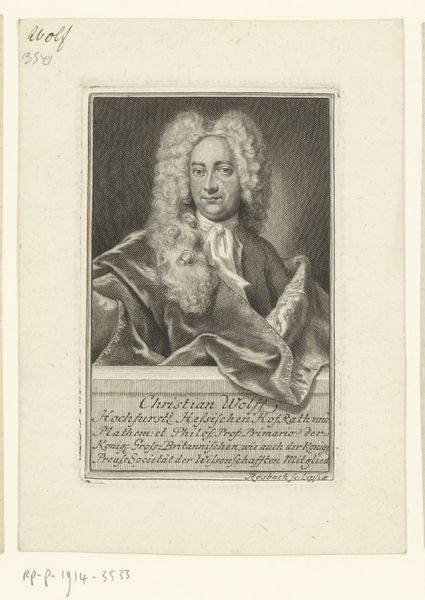

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 152 mm, width 93 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: We’re looking at a baroque portrait from 1729 entitled *Portret van Johann Anton, Graf von Schaffgotsch*. The artist who rendered it is Martin Bernigeroth. It's an engraving, so printed, allowing wider distribution of the Count's likeness. Editor: My first impression is… theatrical. The wig practically *erupts* around his face. It seems like an exercise in excess, an almost comical display of status through hair and attire. Curator: It certainly captures the Count’s importance, but the wig, beyond being a marker of status, I read as symbolic, too. Hair has long represented vitality, virility, power. Here, it's amplified to an almost mythic scale, projecting the image of a powerful man. Editor: Right, but I think the print medium speaks volumes here. Bernigeroth, through meticulous labor and repetitive actions with engraving tools, transforms base metal into matrices of an image: in other words, he renders a high official as reproducible product, blurring the line between individual and image, original and commodity. How would this piece been sold, who worked in his shop? Curator: Interesting to think about Bernigeroth as entrepreneur with an audience. We see this iconography—the oval portrait, the imposing figure presented on a pedestal like ancient orators or heroes—as ways to signal prestige in that period. Note the Latin inscription—a declaration of the Count's titles and governance. It reinforces a carefully constructed persona. Editor: Absolutely. It's image-crafting on a grand scale. A material, etched expression of the man, as a marker for wealth and social position, made from readily reproducible material. You can mass-produce a Count through the printing press. I'm drawn to how that changes the way power works; instead of blood, he's paying to build an icon! Curator: That tension between unique individual and reproducible image adds layers to the print and reflects tensions of Baroque power structures. What might feel theatrical to the modern eye was integral to crafting and broadcasting a noble identity. Editor: Exactly, by recontextualizing and reappraising the materials in question—copper and paper here—I feel we unearth ways this artwork complicates our understandings of individual artistry in Baroque Era, exposing power in novel, reproducible formats.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.