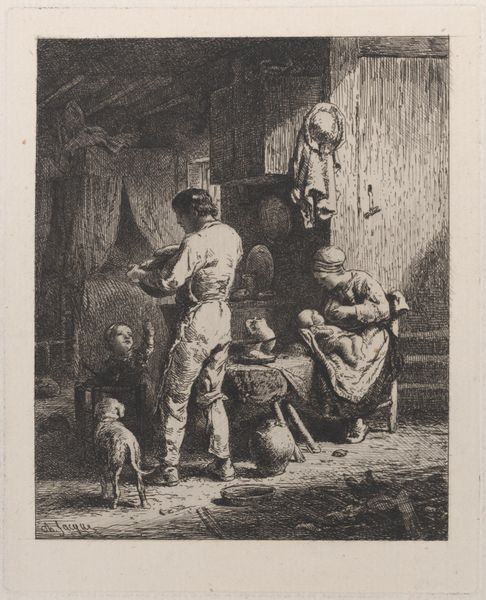

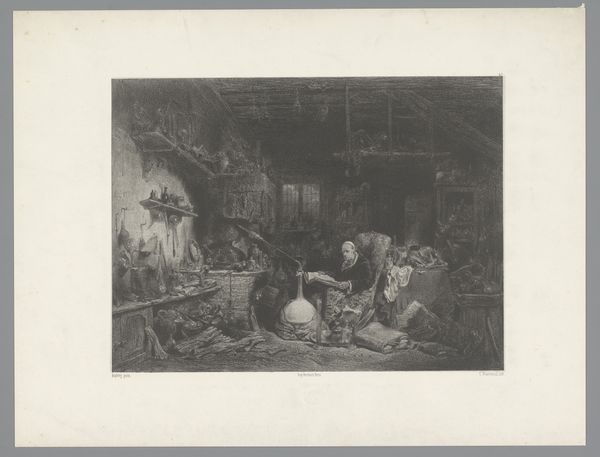

print, etching

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

realism

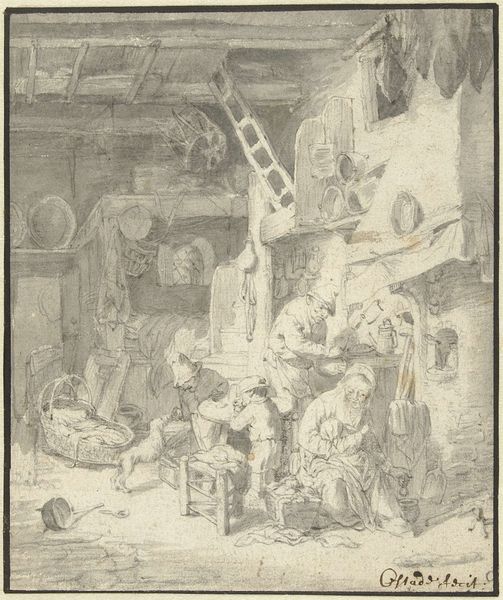

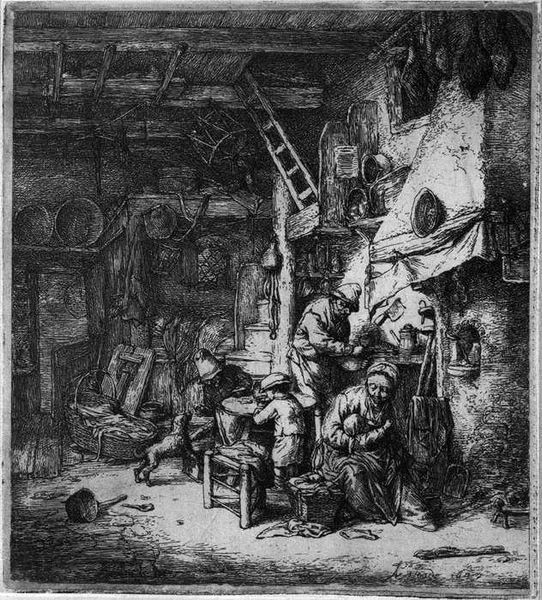

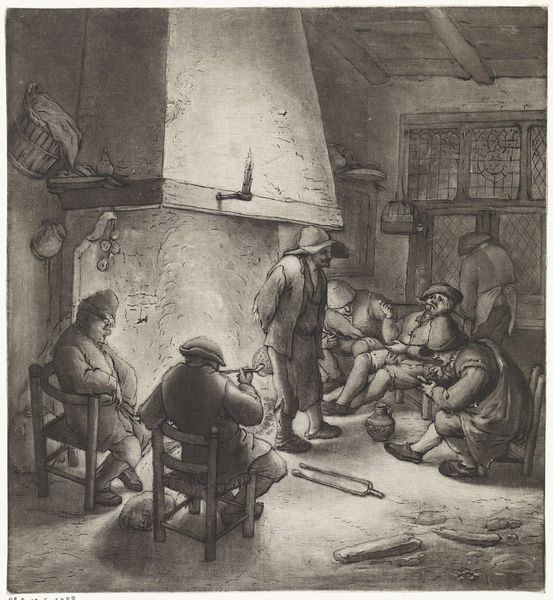

Dimensions: sheet (trimmed to plate mark): 17.8 x 15.8 cm (7 x 6 1/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

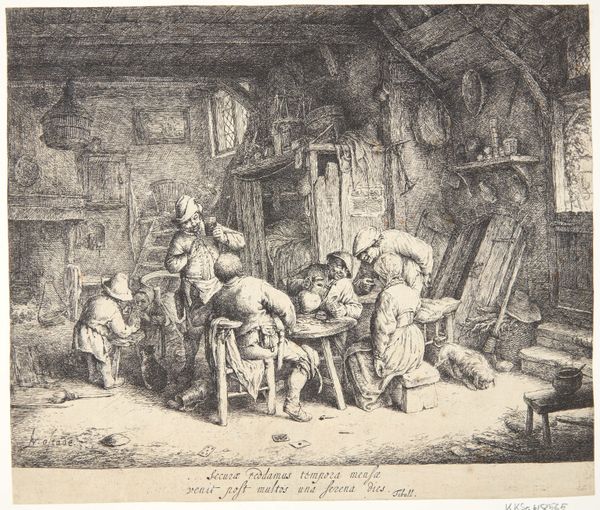

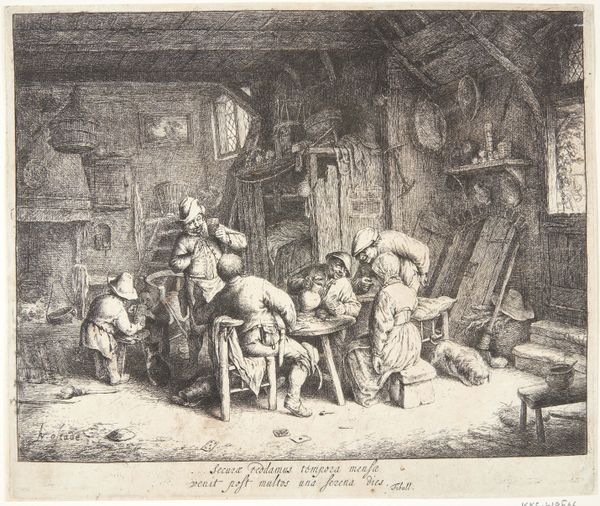

Curator: Here we have Adriaen van Ostade’s "Peasant Family," an etching from 1647. The work offers an intimate glimpse into the daily lives of a 17th-century peasant family. Editor: The overwhelming feeling I get from this piece is… claustrophobia. The etching is so detailed, packed with objects, but it makes this home feel like it's caving in on the family. Is that an intentional commentary on social constraint, perhaps? Curator: Well, it’s fascinating to consider how societal structures informed the reception of art like this. Genre scenes were quite popular, providing glimpses into different social strata, reinforcing established hierarchies. Didactic, almost. But it is also interesting to look beyond genre traditions: Ostade, and many of his contemporaries, used prints like these to create market for his paintings: they sold them or bartered them, and also exchanged ideas about prints across the European art market. Editor: So, more about creating a visual language, but still…look at the mother, practically swallowed by her responsibilities, another child asleep in her arms as the older ones clamor for attention at a small, shared table, that almost oppressive fireplace. The stark contrast between the warm domesticity that genre painting promises and what’s implied. It feels critical to me. Curator: That resonates when we consider the broader socio-economic context. The Dutch Golden Age also was defined by class divides and hardships for many. But there were also powerful innovations that shifted away from aristocracy. Ostade may indeed be presenting more than just a simple genre scene, offering a subtle critique of idealized depictions. The domestic space becomes a site of labour rather than respite. Editor: Exactly. We can look at the print not only through the lens of art history and production and artistic agency, but also as a window into the struggles of women and children, especially. The domestic wasn't necessarily the private and separate place we think of it as today, so its role is as a marker for social dynamics in the 17th Century. Curator: Absolutely, seeing the artist’s hand also within broader structures provides new possibilities for readings of such artwork. By understanding the dynamics of the art market, cultural values of the 17th Century, as well as family arrangements in this work, we start seeing more than what meets the eye at first glance. Editor: Thinking about art like this reminds us that social realities don’t exist in isolation. It enriches my appreciation for Ostade’s ability to convey such complexities in such a simple, compelling image.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.