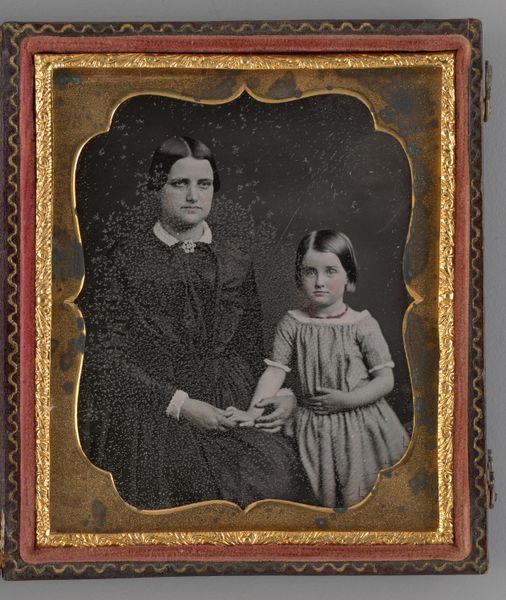

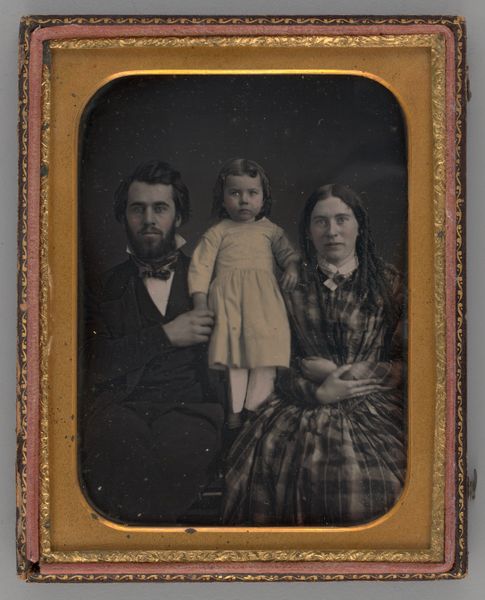

Dimensions: 10.3 × 8 cm (plate, appro×.); 8.4 × 5.9 cm (image, sight); 11.9 × 19.1 × .8 cm (open case); 12 × 9.5 × 1.6 cm (case)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have an untitled daguerreotype, dating back to 1855. The photographer is John Adams Whipple, and the work resides here at the Art Institute of Chicago. It depicts a seated woman and a child. The mother’s dark gown and bonnet create a stark contrast with the child’s patterned dress and wide-brimmed hat. Editor: My first impression is one of restrained emotion. The formal poses, the somber colors... It speaks volumes about the era, the social expectations placed on women. There's a quiet strength in the mother's gaze, though, isn't there? Curator: Absolutely. The rise of photography provided a means for broader representation, though its limitations certainly reinforced existing social hierarchies. Daguerreotypes, for instance, demanded long exposure times. Thus, the subjects often strike stiff poses. This contributes to the overall feeling of formality you observe. Editor: Yes, there's such vulnerability present, considering that need for stillness. The image almost feels sculptural, because it immortalizes the sitters like monuments—yet there’s an undeniable intimacy as well. The mother's hand rests gently on the child. It is such a subtle gesture of protection, defiance. Curator: Indeed, a very keen observation. Daguerreotypes occupy an interesting place in the history of portraiture. They offered unprecedented realism but were initially very costly. Their accessibility gradually broadened, but portraiture remained a marker of social status, often serving a commemorative function. We must also remember photography's complicated role in constructing racial identity in this period. The absence of sitters of color in early photography collections is as telling as the presences of wealthy white sitters. Editor: The child's clothing strikes me, too. That tartan pattern has powerful political connotations tied to the Highland clearances and British imperialism, so its usage here perhaps speaks to complex issues of cultural assimilation or social aspiration. Or simply speaks to Victorian era aesthetics. There is no knowing from only viewing this photographic plate alone, only speculation about its possible origins. Curator: Well put, given that it is very easy to apply a retrospective gaze here. Considering Whipple’s extensive work documenting diverse subjects, we cannot disregard the power of the subject of this photographic plate. As technology was developed during this period, the notion of who, what, where, and how was documented remained a pivotal aspect that impacts today's cultural values. Editor: A fitting reminder. Looking back at it, beyond my contemporary reading of the piece, it is remarkable to contemplate the effort and social ritual in a daguerreotype sitting and to recall the hopes and meanings that it would carry. Curator: Exactly. This one image gives us much food for thought on the trajectory of cultural history and material production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.