daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 95 mm, width 70 mm, height 110 mm, width 84 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

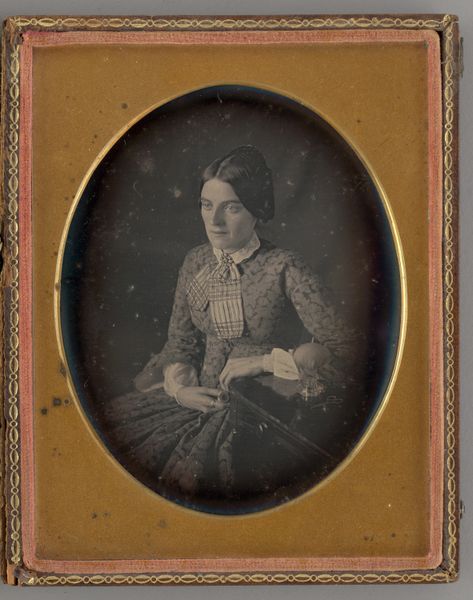

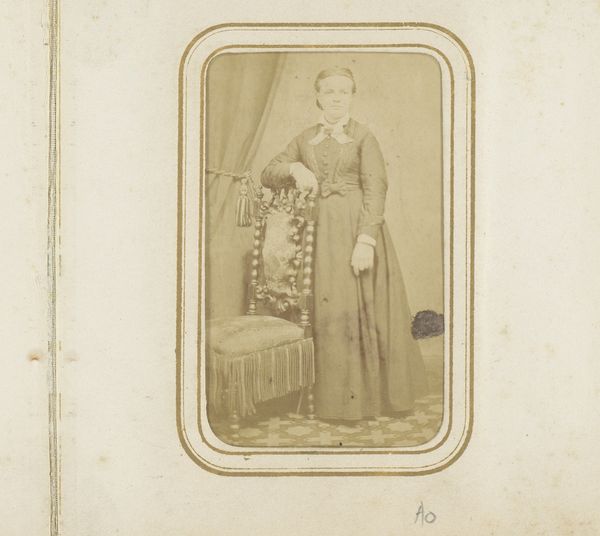

Curator: Here we have an intriguing daguerreotype from around 1855 to 1870, entitled "Portrait of an Unknown Woman with Child in Lap." Editor: It's striking how the ornate gold frame emphasizes the subjects' stillness; a sort of captured moment of profound tenderness amid austerity. Curator: Indeed. Given the time period and the daguerreotype process itself, we can assume this was a significant investment for the family, suggesting an aspiration towards middle-class respectability. The solemnity and the formality speak volumes about societal expectations and perhaps constraints for women during this era. It’s worth questioning what that image-making meant for their identities. Editor: From a structural viewpoint, the contrast between the dark background and the pale faces pulls the eye directly into their embrace, highlighting the familial bond while downplaying any surrounding narrative details. The composition uses sharp contrasts and limited tonal range—common in daguerreotypes—that lend to a spectral feel; a dance between visibility and oblivion, with focus placed squarely on capturing immutable essences. Curator: But think, too, about this photographic encounter. What does it mean to present this almost stark image of motherhood? There’s a raw emotional undercurrent at odds with the stiff posing—perhaps a commentary on maternal stoicism expected of women amid constant pregnancies and high child mortality. It really provokes reflection upon what constituted socially sanctioned performances of affection at the time. Editor: Certainly. Considering semiotics, the texture achieved within the mother's dark dress almost works as a counterpoint to the elaborate lacework or trim upon the child's clothing, introducing dual aesthetics within such a close space and contributing a very tactile depth. The formal constraints imposed end up informing our sensory reception as much as the socio-historical narrative you've provided. Curator: That’s where its power resides, I believe. We have this historical, material artifact intersecting directly with poignant themes relating to motherhood and personhood in a rapidly industrializing Western world. It really allows space to ruminate about visibility, labor, identity, and representation. Editor: It leaves a lot unsaid, inviting us to ponder just what visuality entails, what stories we extract. It truly makes one contemplate what the simple act of looking back means—visually and conceptually.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.