![Untitled [portrait of a mother and child] by Jeremiah Gurney](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzNiNWFjOWIxLTI3M2UtNDg3YS04MTA3LTQwODViMDJlNjRjOS8zYjVhYzliMS0yNzNlLTQ4N2EtODEwNy00MDg1YjAyZTY0YzlfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

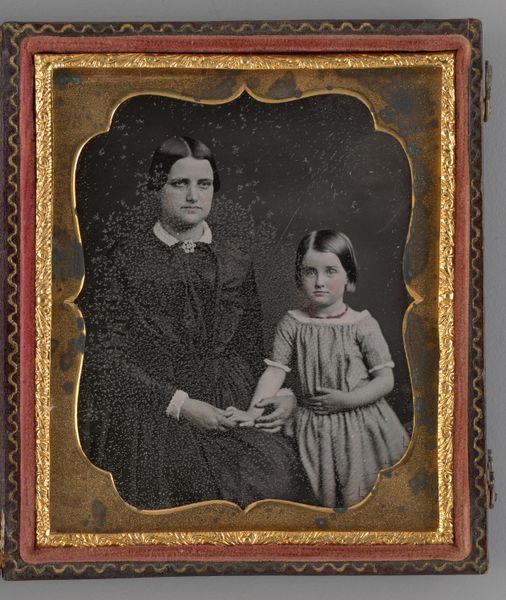

Untitled [portrait of a mother and child] 1852 - 1858

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

group-portraits

#

united-states

#

academic-art

#

brown colour palette

Dimensions: 5 1/2 x 4 1/4 in. (13.97 x 10.8 cm) (image)6 x 4 3/4 x 1/2 in. (15.24 x 12.07 x 1.27 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: We’re looking at an untitled daguerreotype by Jeremiah Gurney, dating roughly from 1852 to 1858. It’s a portrait of a mother and child. There's a real sense of formality, and perhaps a touch of melancholy, despite being a family portrait. What can you tell us about this piece, especially regarding the social context of photography at the time? Curator: The daguerreotype was truly revolutionary. Suddenly, portraiture wasn't limited to the wealthy elite who could commission painted portraits. Here, we see an example of how photography democratized image-making. It allowed middle-class families to participate in visual culture in new ways, solidifying their place within society’s visual narrative. Editor: So it was less about artistic expression and more about accessibility? Curator: Not necessarily. Consider the sitter's pose, her attire, even the elaborate case the image is housed in. These are all signifiers of social standing and aspiration. They project a desired image into the public sphere, a construction of self presented for posterity. Editor: I hadn’t thought about the presentation like that, almost as important as the portrait itself! It's fascinating how a new technology changed who got to be seen, and how they chose to be seen. Curator: Precisely. And think about how studios like Gurney’s capitalized on this desire, shaping the visual language of American identity. These weren't just snapshots; they were carefully crafted performances, reflecting and reinforcing societal values. Editor: Looking at it that way changes everything. I had initially thought of this as a simple family picture, but I see it’s much more complex, showing a new, powerful shift in cultural representation and identity. Curator: And isn't that the beauty of historical analysis? We begin to see not just what is depicted, but who gets to depict, and why.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.