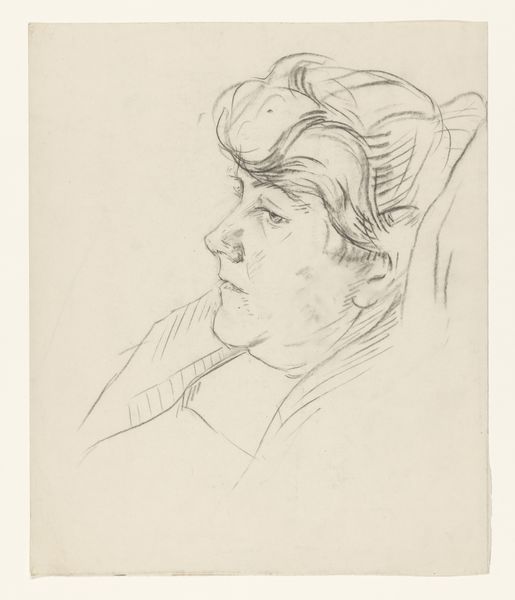

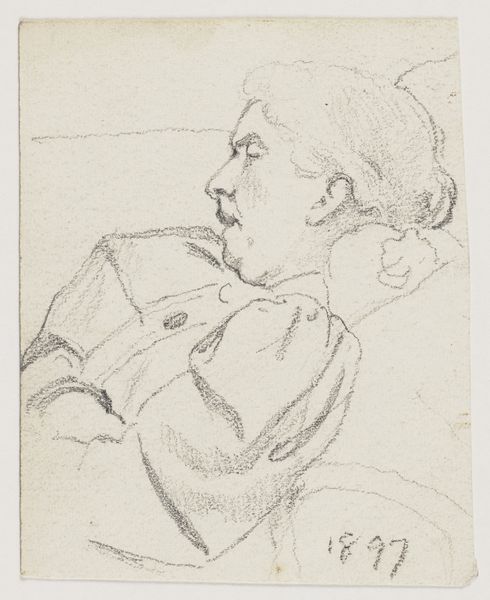

Portret van de vrouw van Wilhelmus Johannes Steenhoff, in bed 1873 - 1932

wilhelmusjohannessteenhoff

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil

portrait

drawing

self-portrait

pencil sketch

pencil

portrait drawing

modernism

realism

Dimensions: height 493 mm, width 325 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, the soft rendering suggests a dreamlike quality. It's fragile, almost ethereal. Editor: Indeed. Here we have "Portret van de vrouw van Wilhelmus Johannes Steenhoff, in bed" which translates to "Portrait of Wilhelmus Johannes Steenhoff's wife, in bed." This pencil drawing, created sometime between 1873 and 1932, offers an intimate glimpse into the life of the artist, now housed at the Rijksmuseum. Curator: The pose is significant. Her gaze is directed away, not engaging the viewer. In some cultures, this averted gaze might represent respect, perhaps humility, yet here it feels more contemplative, introspective even. It invites us to consider her inner world rather than demand our attention. Editor: That's a great point about the gaze. I think it raises questions about the artist’s role as both husband and observer. Was he trying to capture a moment of vulnerability, or to perhaps explore the societal constraints placed upon women within the domestic sphere? What would compel someone to draw their wife as she rests? Curator: Consider the bed as a symbol itself. Across art history, beds represent so many conditions: rest, illness, vulnerability, intimacy, birth, and even death. The cultural coding of the bed in visual language holds heavy connotations and contributes significantly to the emotional resonance of this image. It's charged. Editor: Absolutely. And by positioning his wife within this symbolic space, Steenhoff situates her within a particular narrative and artistic tradition. This challenges our reading: it is tempting to see it as a simple expression of love or private reflection, yet the decision to render her likeness within such loaded iconography complicates such a reading, and draws the viewer into broader historical interpretations of the politics of observation. Curator: It is interesting that this work is also labeled a self-portrait; it begs the question if there's also a reflection of Steenhoff himself and his gaze upon his partner reflected in the rendering of the artwork. Editor: Right, ultimately, the piece becomes a space where we can reflect upon both personal relationships and societal structures during this historical moment in art and culture. The domestic gaze and rendering can bring multiple meanings. Curator: The drawing asks us to look closely not only at the image, but how art depicts human experiences that continue to shape us even today. Editor: A pertinent reminder. Thank you for this reading of the work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.