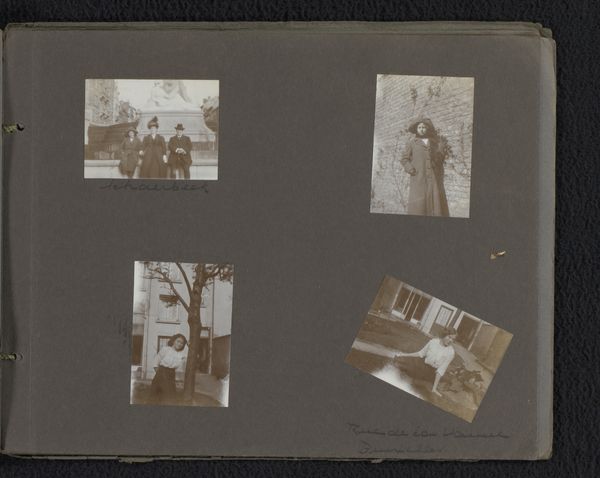

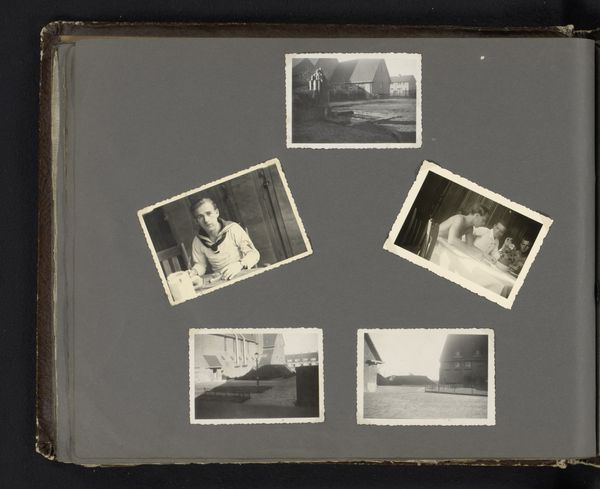

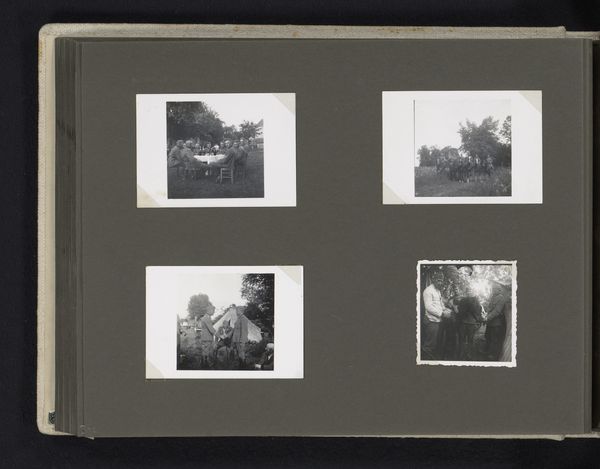

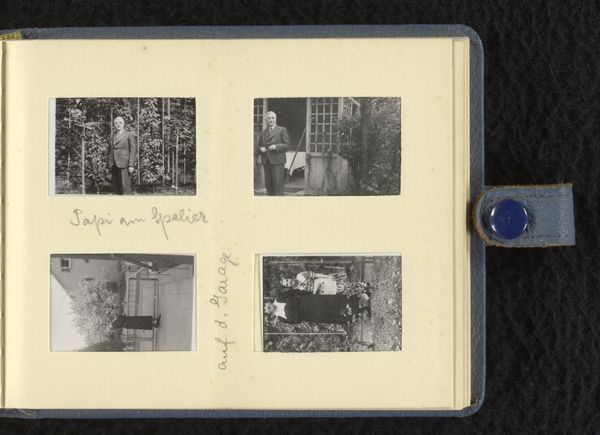

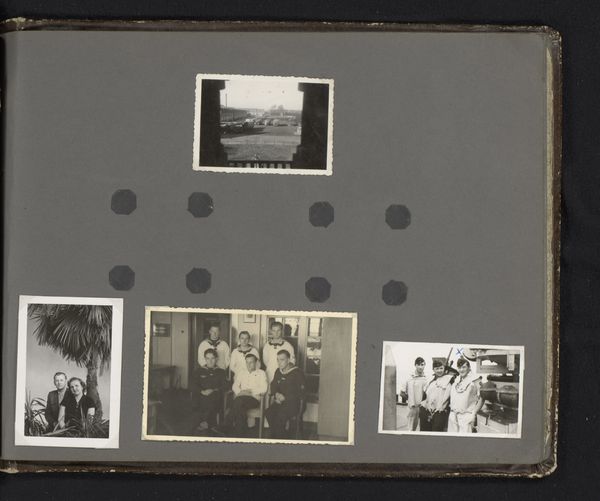

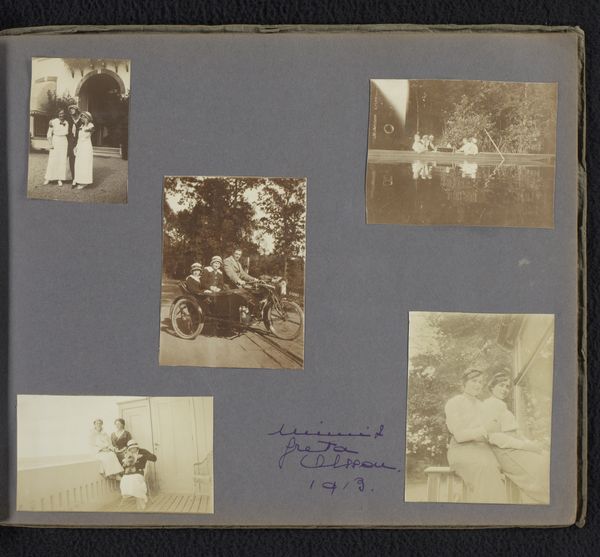

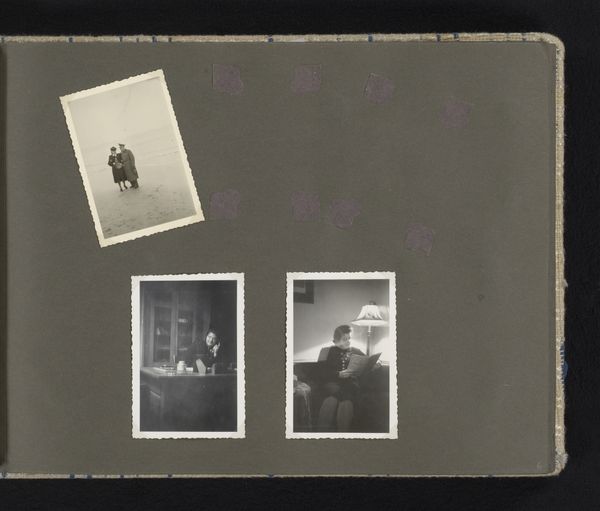

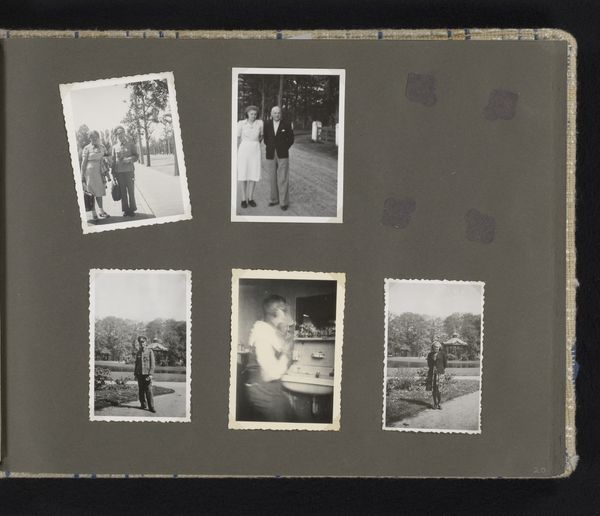

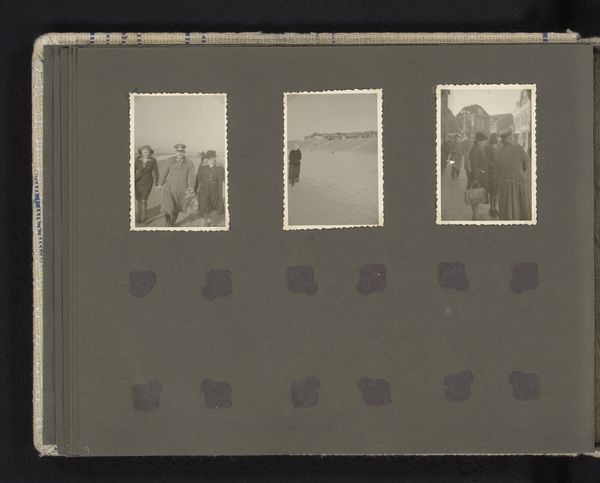

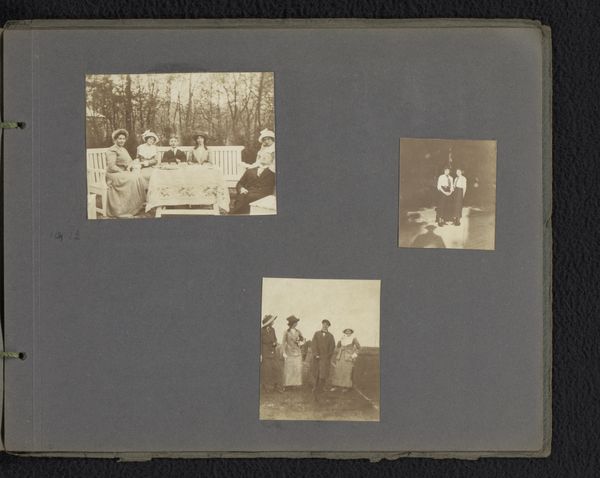

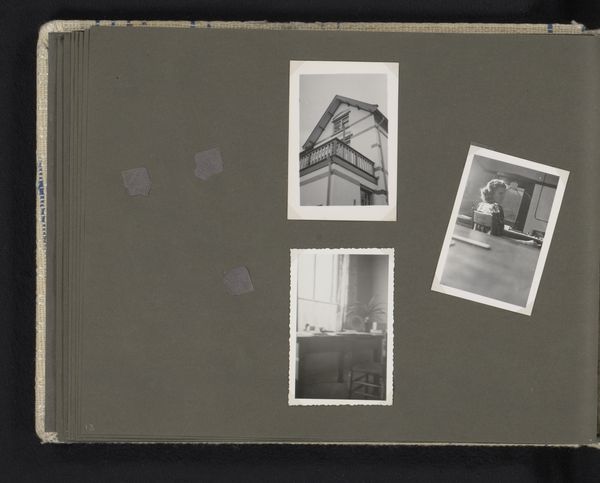

De buurt waar de familie Wachenheimer woonde en Isabel Wachenheimer met haar moeder Else Wachenheimer-Moos in de woning van de familie Wachenheimer (Van Aerssenlaan 22), 1939, Rotterdam 1939

0:00

0:00

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 33 mm, width 44 mm, height 85 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this photograph, a gelatin silver print from 1939, captures the Wachenheimer family's neighborhood in Rotterdam. It feels incredibly intimate and domestic, but I can’t help but wonder about the larger context given the date. What do you see in this piece that maybe I'm missing? Curator: It’s poignant to view these snapshots knowing what was looming for Jewish families in Europe. The family album format itself speaks volumes. It’s an attempt to document and preserve a sense of normalcy and belonging just before their world was shattered by the Holocaust. These aren't just personal photos, they're carefully constructed self-presentations of identity within a community. How does that impact your reading of the images? Editor: That adds a layer of… desperation, almost. The landscape photographs, the portraits, they suddenly read as a defiant assertion of their right to be there, to simply exist within that space. The act of photography then becomes a political one. Curator: Exactly! Consider the act of displaying these photographs. A museum, by showcasing these intimate portraits, shifts their meaning. They are no longer solely private memories; they become evidence of a life, a community, that was targeted and erased. How does this reframing affect your perspective on their aesthetic qualities? Editor: It's hard to separate the historical weight from the artistic elements. The everyday nature of the photos – almost amateur in style – becomes a strength. It emphasizes their vulnerability, their humanity. It reminds us that these weren't just victims of history, they were people living their lives. Curator: Precisely. This work pushes us to consider the power dynamics inherent in visual representation, especially in historical contexts marked by trauma and loss. Editor: I see how these photographs become active agents, bearing witness and challenging us to remember the individuals erased by history. It gives a completely different meaning to that family album! Curator: Indeed. And perhaps more than a personal family history, a communal one, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.