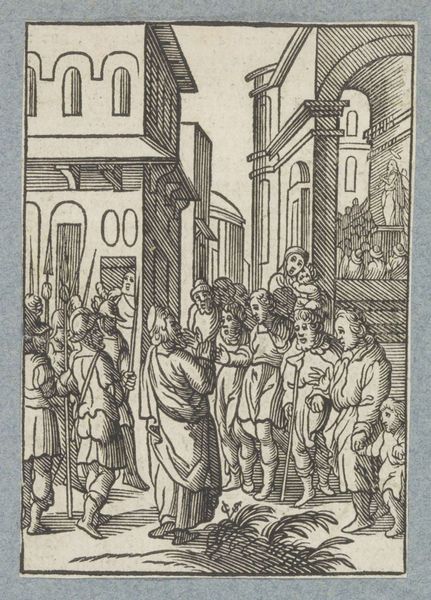

Christ before Caiphas, from the Passion 1472 - 1553

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, woodcut

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

soldier

#

woodcut

#

men

#

northern-renaissance

#

christ

Dimensions: Sheet: 10 × 6 13/16 in. (25.4 × 17.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Lucas Cranach the Elder and his workshop, between 1472 and 1553, created this striking woodcut, "Christ before Caiaphas, from the Passion," now housed at the Metropolitan Museum. It’s intensely stark. Editor: Yes, a harsh rendering. The figures are compressed together, the black lines almost aggressively delineating the forms. There's a tension, a sense of impending violence. Curator: Woodcut lends itself to such stark contrasts. The physicality of cutting into the block, the removal of material to create the image. Consider the labor involved. It wasn't merely about aesthetic representation; it was a craft rooted in physical effort and readily reproducible imagery. These prints were commodities circulating in Reformation Europe. Editor: Absolutely. And the content—Christ before Caiaphas—was politically charged. Images like these would have circulated amongst the public, shaping opinion during a period of immense social upheaval with the reformation and the emergence of printing. It is no accident it comes to the hands of regular people with strong political will. Curator: Exactly. Cranach was working for the Wittenberg court of Martin Luther. How did the accessibility of printmaking aid in the distribution and consumption of visual information during the rise of new religious and political beliefs? The image could be mass produced. Think of this woodcut as proto-propaganda. Editor: Note the architectural details of the building. The mocking sculpture overlooking Caiaphas' judgment. Cranach is making pointed commentary on corrupt institutions here, framing Christ as being at odds with secular structures. Curator: Yes, and let’s think beyond the obvious religious symbolism, the suffering of Christ. This object reminds us how material processes, artistic techniques, and social purpose were fused. The rough, tactile qualities of the woodcut became intrinsically linked to the radical message that spread. Editor: Looking closer at its display at the Met—a place which in itself has historically cemented much more than just art, a symbol of power. I wonder what messages does its place there send nowadays in its new contemporary audience. Curator: Quite right. In closing, Cranach's woodcut offers us not simply an artistic statement but also valuable insight on the intermingling of belief, method and socio-political movement in 16th century Europe. Editor: Indeed. The visual force, when properly recognized for its context and intention, delivers an exceptional charge of thought.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.