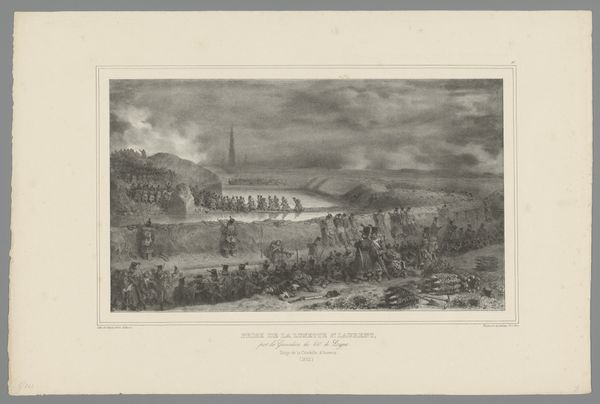

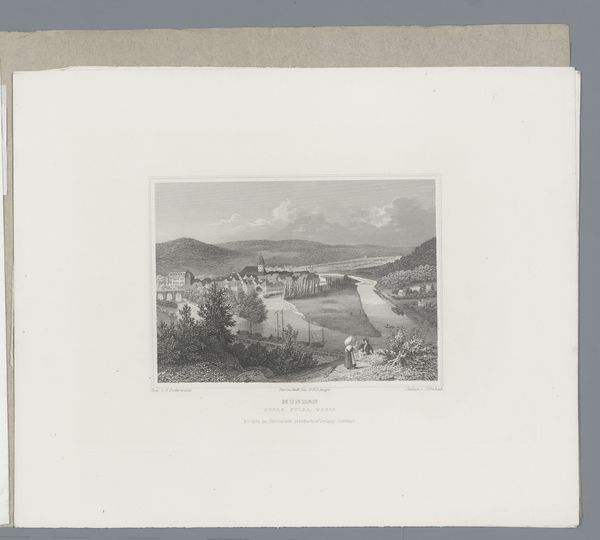

Franse en Afrikaanse soldaten in gevecht met de Arabieren, 27 november 1836 1837

0:00

0:00

augusteraffet

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

# print

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 357 mm, width 548 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is “French and African Soldiers in Combat with the Arabs, 27 November 1836,” an engraving by Auguste Raffet from 1837. It’s quite a scene—so much chaos and movement! What’s striking is the stark contrast between the dense cavalry charge and the more static French infantry. How do you interpret this work? Curator: Well, looking at this print, I’m immediately drawn to the visual encoding of colonialism and the “civilizing mission” of the French. Raffet depicts a specific moment – a charge on the Algerian city of Constantine – that speaks to a broader, more fraught historical narrative. Notice how the “French and African” soldiers are presented. The use of “African” in the title flattens the complex diverse origins to those who were forcefully engaged in the conflict. Editor: So you see this less as a straightforward battle scene and more as a visual argument? Curator: Precisely. Think about who this image was intended for: a European, likely French, audience. It portrays France's colonial endeavors as bringing order and civilization to a seemingly chaotic “Arab” world. Consider also the visual language: the French infantry, depicted with clear lines and organization, stand in contrast to the almost amorphous mass of the charging cavalry. This juxtaposition subtly reinforces a sense of European control and rationality versus perceived Arab disarray. Editor: That's interesting; I hadn’t considered the intended audience so directly. Does the date – 1837 – further contextualize the work's meaning? Curator: Absolutely. This image appeared relatively early in the French colonization of Algeria. It played a role in shaping public opinion and justifying the colonial project. We should ask, how did images like these shape perceptions of the "Other" and legitimize imperial ambitions? How did they construct narratives of power and difference? Editor: This really makes me think about how art functions not just as a record but as a powerful tool shaping our understanding of history. Thanks. Curator: Indeed. It highlights how art is always embedded in networks of power and meaning, playing an active role in shaping social and political realities.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.