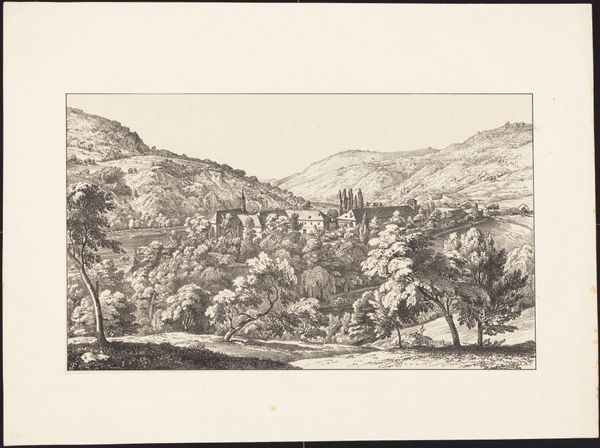

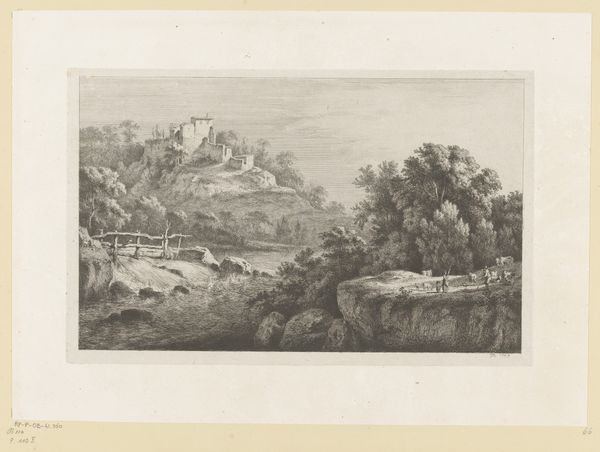

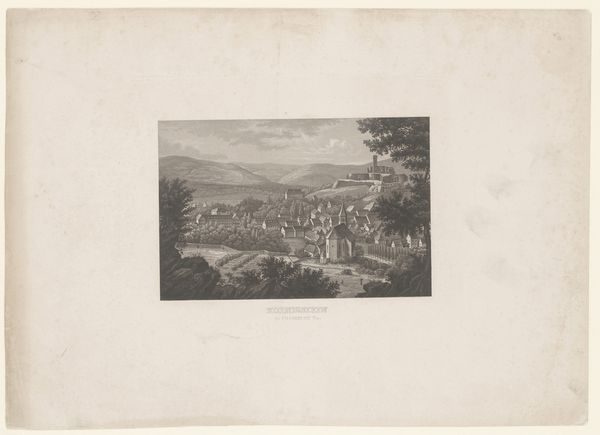

print, paper, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

paper

#

romanticism

#

line

#

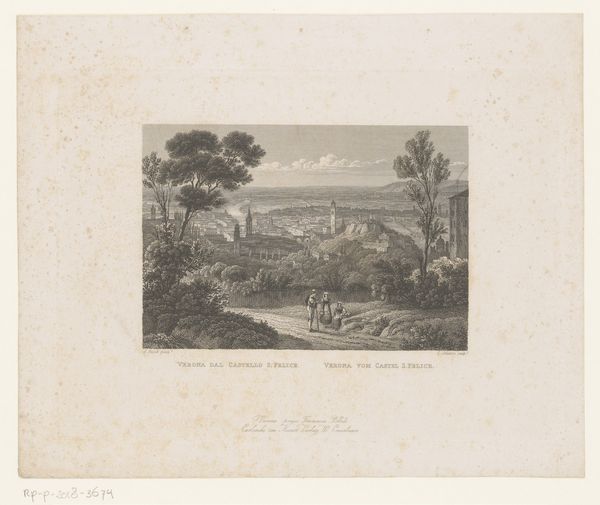

cityscape

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 192 mm, width 280 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a 19th-century print called "Gezicht op Eisenach," author is anonymous, done with engraving on paper. The detail is incredible for such a small work. It makes me think about idealized visions of nature, a place of harmony between people and land. What's your read? Curator: It's interesting that you picked up on the "harmony" of the piece. I wonder, however, if that harmony wasn't also masking some of the social realities of the 19th century. Think about land ownership, for instance. Who has access to this idyllic scene? Who is excluded? The figures in the foreground seem like landowners gazing upon the world below them, a manifestation of what was happening during industrialization and urbanization in Europe. Editor: That's a perspective I hadn't considered. So you see this landscape as less of a neutral observation and more of a statement about class? Curator: Not necessarily a conscious statement, but certainly reflective of the power dynamics inherent in land ownership at the time. What does it mean to depict a landscape as belonging to someone, implicitly or explicitly? What is represented and what is silenced through its idyllic lens? Editor: I see your point. By focusing on the picturesque, the print subtly reinforces the status quo. Were there artists at the time who directly challenged that vision? Curator: Absolutely. Consider Gustave Courbet, who challenged conventional Salon painting with works depicting working-class people in their daily lives, or Honoré Daumier's lithographs, offering sharp social critiques. They offer contrasting representations that engage with questions of labor, inequality, and power dynamics. This comparison allows us to question the social position of landscapes such as "Gezicht op Eisenach." Editor: This has given me so much to think about—how art, even seemingly straightforward landscapes, can be interpreted through these cultural and political lenses. Curator: Precisely! By questioning what we see and considering the context in which it was created, we start to have more fruitful and profound engagements with art and its significance in our contemporary world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.