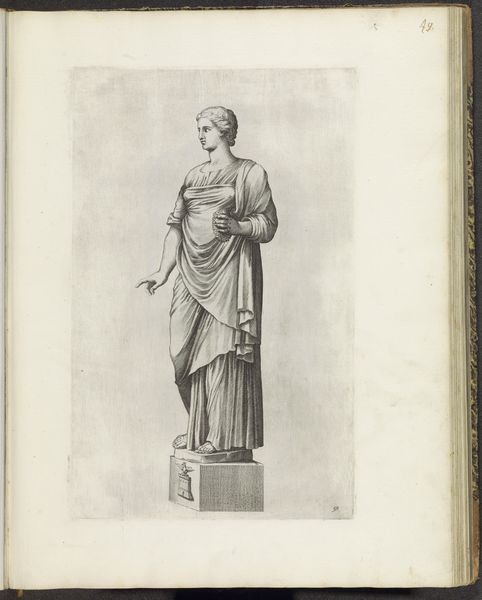

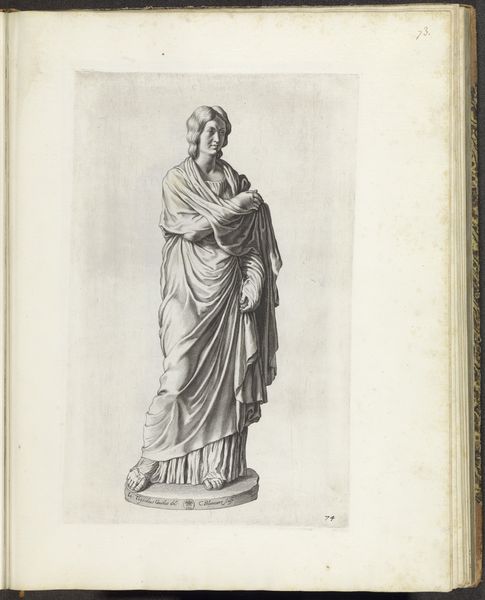

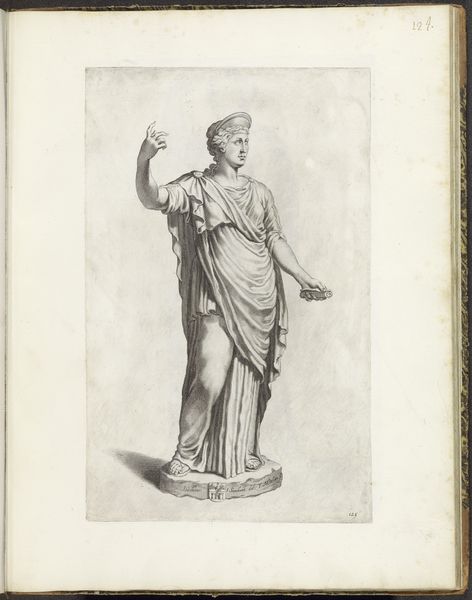

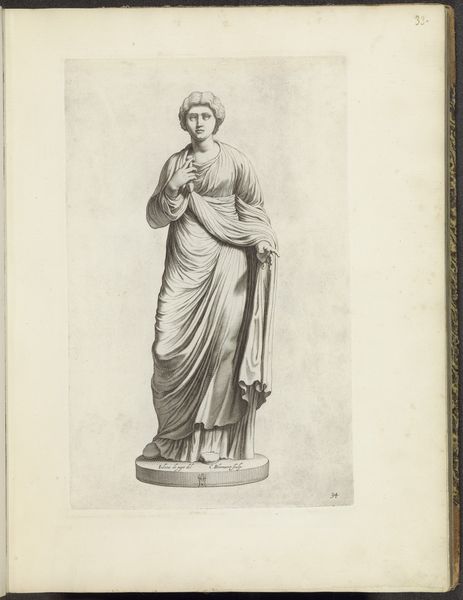

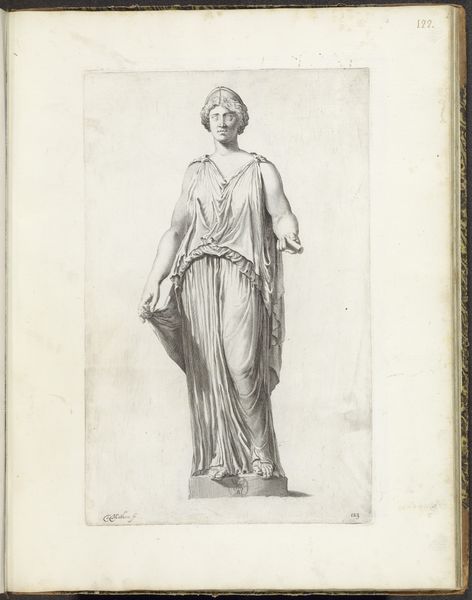

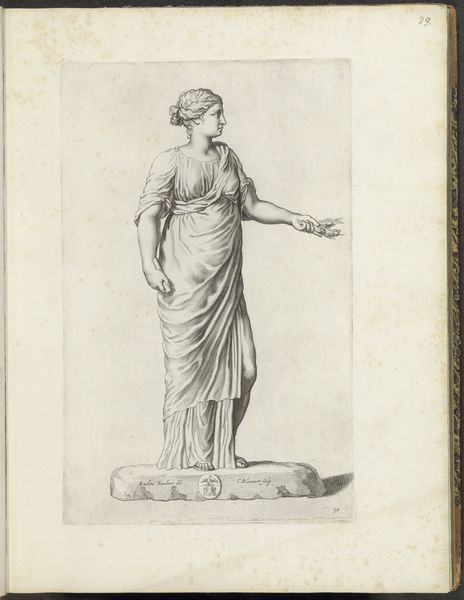

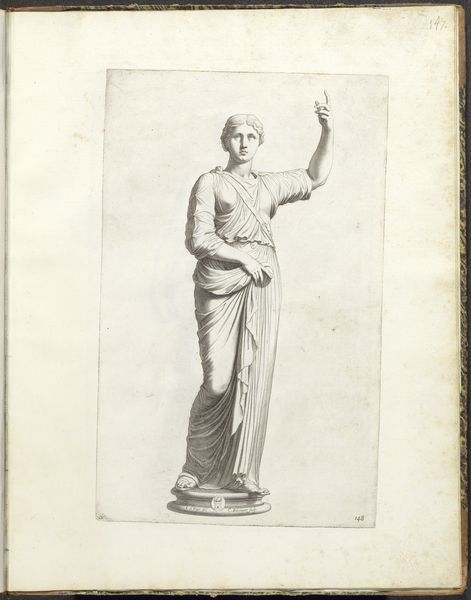

print, metal, sculpture, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

metal

#

figuration

#

form

#

romanesque

#

sculpture

#

line

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 372 mm, width 230 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

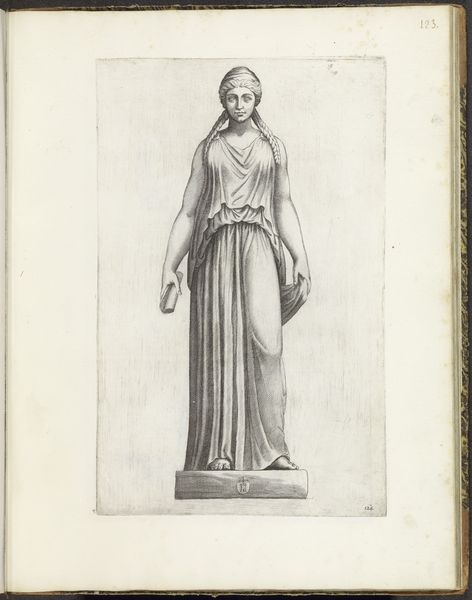

Curator: This engraving, created between 1636 and 1647 by Pieter de Bailliu, captures a statue of a consul in a toga holding a scroll. It's currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: There's something deeply unsettling about this. The stark lines of the engraving, combined with the severe expression on the consul's face, give it a very clinical, detached feeling. It's almost like a medical illustration, but for a soul, maybe? Curator: Interesting. For me, the engraving elevates the statue. De Bailliu's lines are so precise they make the toga almost feel like fabric, capturing the essence of Roman idealism while also showcasing craft—metal engraving—at its finest. Do you find it a successful method for preserving sculpture’s essence? Editor: Method is everything. Think about what it meant to reproduce an image like this then—etching and engraving were specialized labor, creating accessibility for some, yet still very expensive for most. Reproducing Roman ideals had less to do with preserving them and more about placing oneself in a lineage of power through images, no? It makes one wonder if it reflects more on Bailliu’s time than the Consul's. Curator: That’s quite insightful. You're making me think about the engraving as less of a straightforward representation and more of an interpretation filtered through Bailliu's own context and intentions. A little like gossip—'Here’s what *they* stood for'. I also suspect there’s a great deal about the Romanesque aesthetic that artists were attempting to revisit. Editor: And to capitalize on, no doubt. The question is, did de Bailliu truly consider the materiality of that sculpture or focus primarily on surface representation, on selling us the illusion of power. How could you capture, or rather replicate, marble using metal? How does that reflect craft versus artistic sensibility, too? Curator: Fair point. And perhaps that tension, between wanting to faithfully represent and the inherent limitations of the medium, is precisely what gives the print its… strange charge. He must make so many artistic and, really, practical decisions along the way. Choices like the use of very stark light or dramatic contrasts, might have served that very ‘clinical’ feeling you pinpointed in the first place. Editor: Right, those stark lines tell more about the labor, the material intervention—a whole social framework— than any eternal consular dignity. But thinking this way helps us see its value—it preserves something real for us that may not have been intentionally communicated to the viewer. Curator: Well, looking closely and considering context always yields hidden insights. Editor: It often does. Thanks for shining a light on that!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.