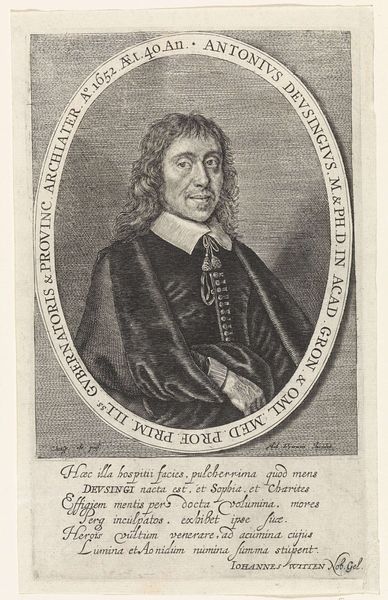

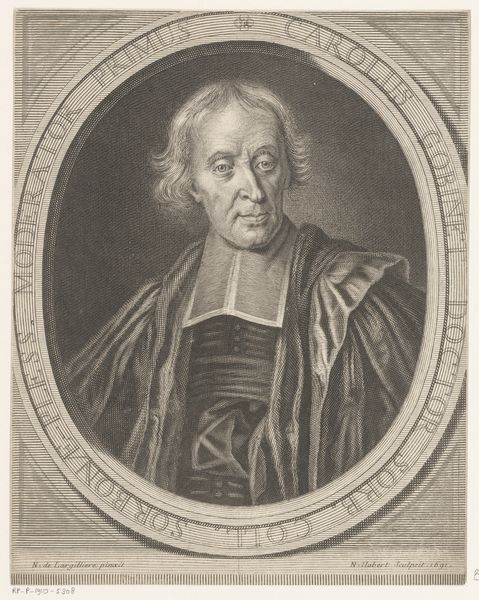

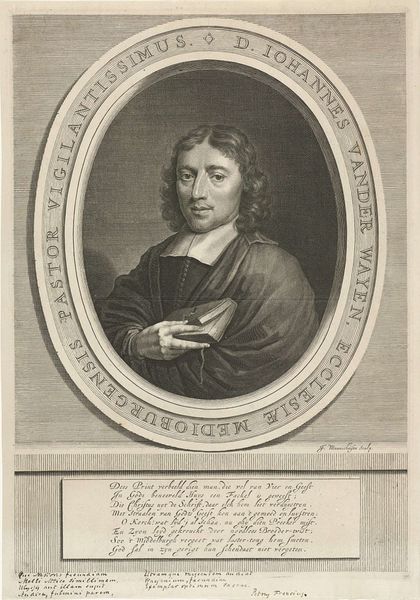

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 215 mm, width 129 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Crispijn van de Passe the Younger created this engraving in 1652, titled "Portret van Johannes Steinbergen." It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The intense crosshatching gives it a certain somberness. The detail is remarkable, particularly around the face, but the overall tone is rather melancholic, wouldn't you agree? Curator: Considering the historical context, this makes sense. These portraits often served commemorative and pedagogical purposes. Steinbergen was a legal scholar; the engraving was likely intended for a book or broadside honoring his work and status. Editor: You're right, the subject matter speaks of status. The engraving itself, with its dense lines and use of Latin inscriptions framing the portrait, evokes a sense of serious, academic weight. One can imagine the intense labor to cut that plate! Curator: Absolutely. Van de Passe operated within a network of printmakers serving scholarly and elite circles. These portraits helped disseminate ideas but also reinforced a hierarchy of knowledge and power. The Baroque style amplified such messaging. Editor: Tell me more about the materiality itself; what would have this process been like? I find the subtle nuances, how the density of line varies to create light and shadow, incredibly compelling in revealing process and artistry. Curator: Well, copper engraving demands precision. Van de Passe used a burin to cut lines directly into the plate. Each line required deliberate pressure and control, a significant investment of time for such detail. And it could create hundreds or thousands of reproductions. Editor: I wonder what sort of working-class artisans were part of producing prints. Engraving, despite representing the elite, necessarily relied upon a much broader labour system for circulation. It makes one reflect on class dynamics in Dutch society in that era. Curator: Examining it in this way shifts our understanding, certainly. The portrait immortalizes an individual, yet also represents the systems and social relations from which this individual gained authority. Editor: Indeed, and paying attention to the engraver allows us to grasp both how material conditions impacted artistic form, but how these artistic objects served, reproduced, or, at times, even subtly challenged power structures. Fascinating.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.