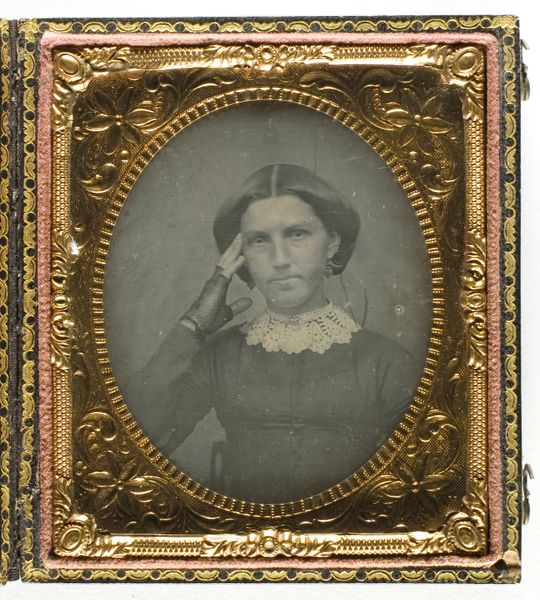

daguerreotype, photography

#

portrait

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

oil painting

#

miniature

#

realism

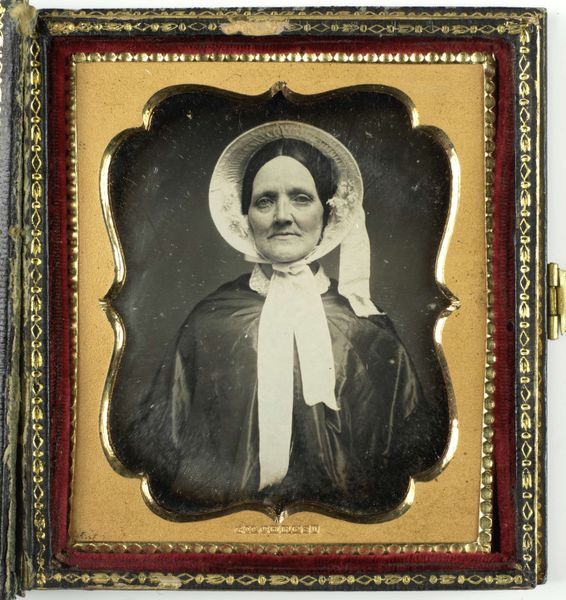

Dimensions: image (visible): 5.1 × 4 cm (2 × 1 9/16 in.) mat: 6.2 × 5 cm (2 7/16 × 1 15/16 in.) case (closed): 7.3 × 6.19 × 1.59 cm (2 7/8 × 2 7/16 × 5/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: So, this is "Portrait of a Woman," a daguerreotype from around 1850 by an anonymous artist. It feels so intimate, almost like peering into a private moment from the past. What do you see when you look at this portrait? Curator: I see more than just a face; I see a commentary on the constraints and expectations placed upon women during this period. The formality of the pose, the tightly clasped hands, the demure expression – these aren’t just aesthetic choices. They reflect the limited agency afforded to women, their prescribed roles within a patriarchal society. Editor: I hadn't really considered the pose that way. I guess I just saw it as "how people posed back then." Curator: Exactly. The daguerreotype itself becomes a symbol. Photography was relatively new, and the act of capturing a woman's image, while seemingly progressive, also served to objectify and control. Consider the anonymous artist; was this a professional commissioned work, or a more personal—and therefore, perhaps, a less powerful—interaction? Editor: That's interesting. It makes me wonder about the woman’s own desires in participating. Did she have any say in how she was presented? Curator: Precisely! We have to question the narrative being presented to us. The very act of preservation through a daguerreotype raises issues of class, access, and the potential erasure of individual stories. Editor: Wow, I’m definitely seeing this in a new light. Thanks for that perspective! Curator: And thank you for reminding me that even historical portraits are ultimately conversations about the present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.