#

pencil drawn

#

aged paper

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

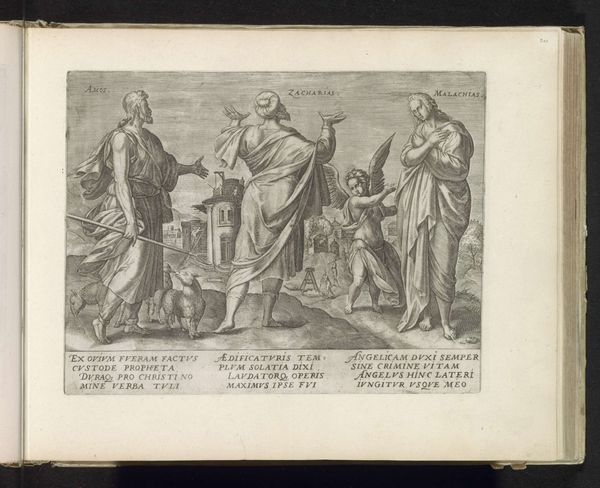

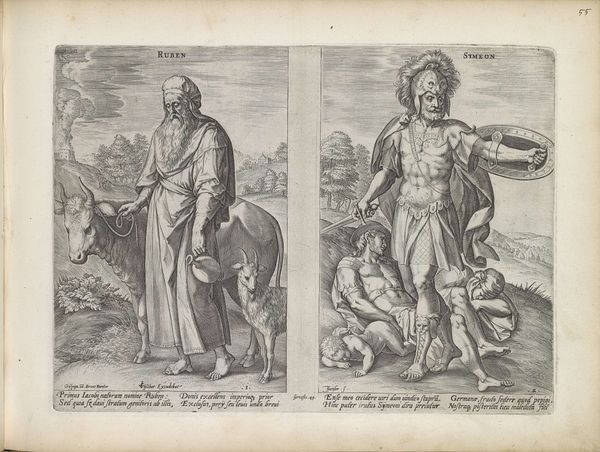

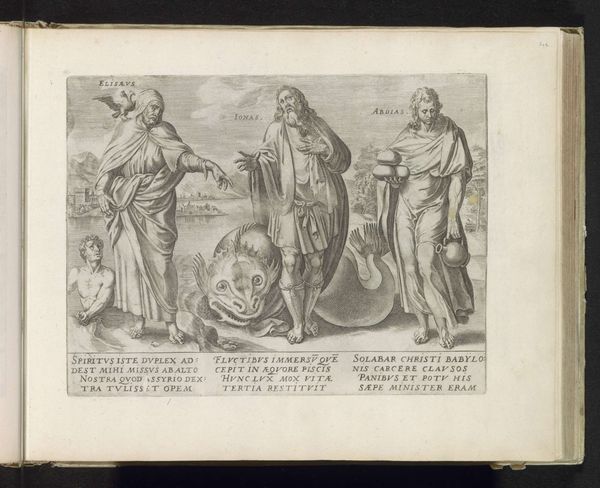

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

sketchbook art

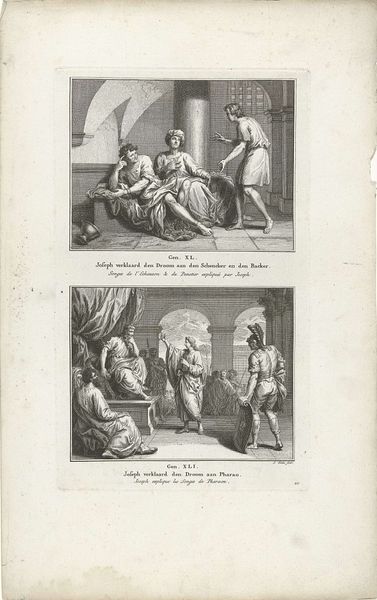

Dimensions: height 94 mm, width 141 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

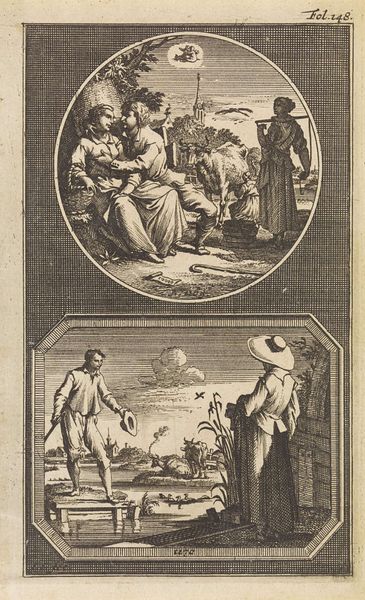

Curator: This is a print titled "Edelman uit Venetië en zijn vrouw Paulina" by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger, created in 1641. The print presents us with two distinct oval compositions. What's your initial response? Editor: It's stark. There's a strange coolness to the composition despite the rather suggestive nature of the pairings. There is this almost clinical assessment of this older, wealthy Venetian next to the almost too familiar gesture between the woman and younger blindfolded male figure. Curator: Precisely! This work comes from a time when the Dutch Republic was grappling with very visible socio-economic shifts and related cultural anxieties. Venice, known for its courtesans and open sensuality, became a loaded symbol for anxieties about moral decline. So while it might seem like a somewhat risqué or voyeuristic image for us today, it operated as moralizing satire at the time, particularly as connected to political changes within Dutch society. Editor: Satire through symbolism. Look at the older Venetian—he is carefully examining himself with what looks like a looking glass, a mirror or spyglass to see close details...The inclusion of the Venetian skyline situates him, gives us context. He's enclosed within his oval—self-contained. Yet Dona Paulina is intimately entwined with a younger man whose eyes are covered—a denial of vision or judgment? Curator: The visual language would certainly speak to the audience then about female agency and its disruption of a traditional family structure. Remember, this work exists alongside moral debates concerning women's roles in the public and private sphere. Some historical research suggests she and her companion may have engaged in the production of pornography, at which point it becomes clearer about the potential for self-determination amidst limitations within strict class- and gendered social hierarchies. Editor: The symbolism, then, acts as a powerful shorthand. Even without reading the text accompanying the images, we understand there's a disruption of power at play, a critique of Venetian decadence and wealth, and of marital fidelity, through this particular kind of romantic exchange. And for us as viewers of this era, even lacking the same social and ethical context of its creation, it retains some form of suggestive meaning as well. Curator: Yes, a work of art created in 1641 invites us to consider shifting cultural touchstones and consider what forms, practices, values, and virtues remained constant and have changed through time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.