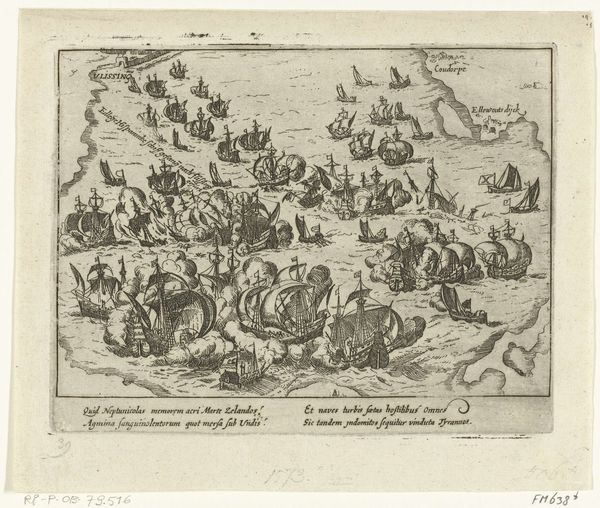

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 136 mm, width 160 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have an engraving called "Slag op de Kauwensteinse dijk, 1585," dating from around 1613-1615. It's anonymous, but held at the Rijksmuseum. The detail is incredible for a print – you can almost feel the chaos of the battle. What strikes you when you look at this piece? Curator: What immediately grabs me is the process, the *making* of this image. Engraving – that's meticulous labor. Look at the lines: each one is a conscious decision about representation. And it was produced to be reproduced. Consider the social context; this wasn't fine art for a palace, it's a widely disseminated image about warfare. What does that mean about accessibility of information in this period, or about the value that they assign to the making of a visual account of history for wider consumption? Editor: That's a fascinating point, I never really thought about it in those terms before. Are you saying that the printmaking process itself – the conscious crafting and widespread availability – directly informs the image’s message? Curator: Precisely. Think about the engraver's skill, the physical demands, how these skills were acquired and passed down in workshops, and the economics behind them. This isn't just *representing* a battle; it is labor memorialized, a testament to skilled craftsmanship intended for broad consumption, produced for a specific function, by the labourer’s hands. Editor: That definitely changes my perspective. I was so focused on the depicted battle itself – who was fighting whom – but now I'm much more aware of the layers of work, purpose, and skill it took to make. It brings new questions to my mind about the materials and process and context. Thanks for pointing that out. Curator: Absolutely. Thinking about art as labor challenges the traditional notions of 'genius' and forces us to reconsider the value we place on artistic production itself, especially within specific economic contexts of the era. It certainly moves it beyond simply aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.