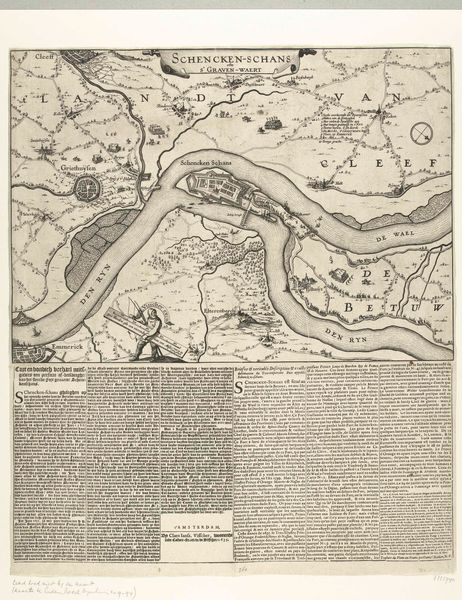

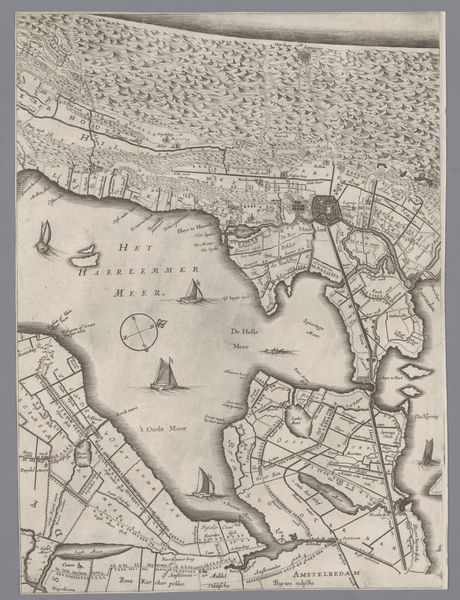

print, etching, engraving

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

mechanical pen drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

landscape

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

thin linework

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

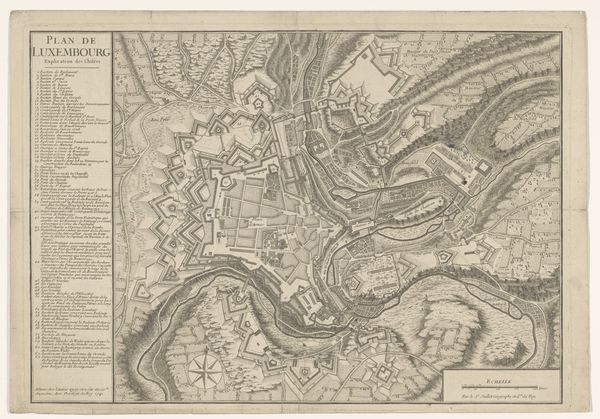

cityscape

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

engraving

#

initial sketch

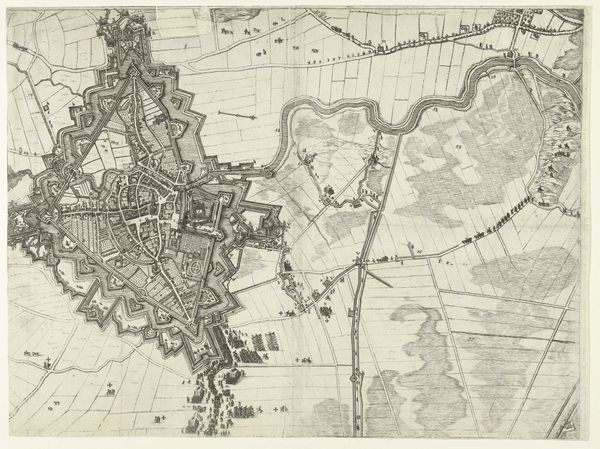

Dimensions: height 580 mm, width 467 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

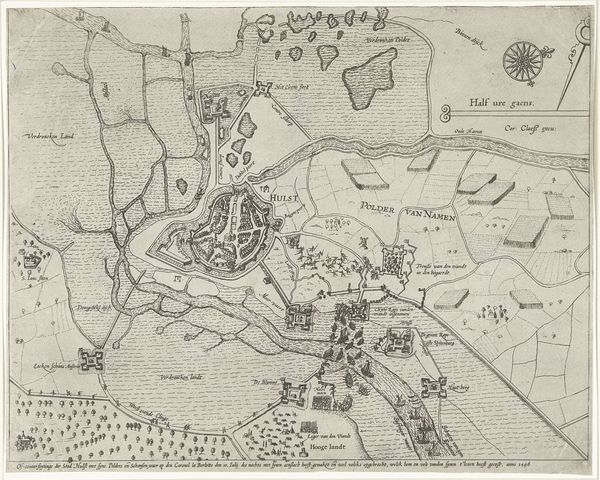

Curator: It’s amazing how much detail they managed to capture in this etching. I believe the Rijksmuseum holds a piece entitled "Grote kaart van het beleg van Maastricht, 1632, plaat 5" created in 1632 by Salomon Savery. What strikes you first about it? Editor: Well, immediately, I see power—power meticulously mapped and deployed. The visual language screams domination, both of the physical space and, perhaps more insidiously, of knowledge itself. Curator: Precisely. Consider the symbolism inherent in mapping—taking something organic and complex like a city under siege, reducing it to a grid, to manageable components. It’s about asserting control. Notice how the cityscape transitions into the open fields; a deliberate act to depict a city's most vulnerable attributes when encroached upon. The style in Dutch Golden Age clearly suggests the importance of landscape elements when narrating a moment in history. Editor: Absolutely, and maps, historically, haven't been neutral documents. They are ideological statements, reflecting who has the power to define and represent space. Look at the positioning of the attacking forces depicted in what appears to be temporary structures across the southern border of Maastricht. Curator: We see how cartography marries with military strategy. Each etched line denotes strategic advantage. You see how he uses the wind rose? This isn't just a map, it is a tool. A weaponized landscape. The depiction, even divorced from the actual siege, reinforces ideas about spatial hierarchies. Editor: That's chilling, isn't it? And speaking of symbolic load, water holds a prominent place on this map; we see the Maas river to the north. Water represents passage but also a boundary and therefore restrictions. Curator: The etching medium, itself, with its precise, almost surgical lines, contributes to this sense of cold, calculated observation. Each tiny house, each fortification rendered with an almost inhuman objectivity. Editor: And isn't that objectivity a facade? What's absent here are the people, the suffering. The lived reality of the siege is neatly erased in favor of a sanitized, strategic overview, typical of early Baroque landscape artistry when the human presence, although central to its activity, is still depersonalized as it melds with its landscape. Curator: Indeed. It serves as a reminder that even the most seemingly objective representations are always filtered through a lens of power, sanitizing events that can cause mass suffering in an effort to preserve historical legacies. Editor: Exactly, looking closely reveals its inherent biases. It urges me to question the narratives presented.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.