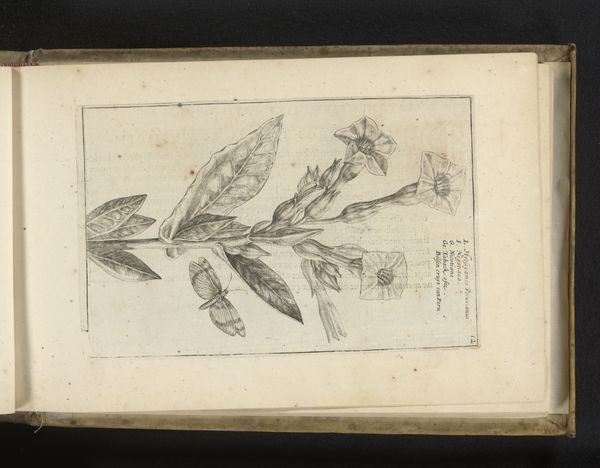

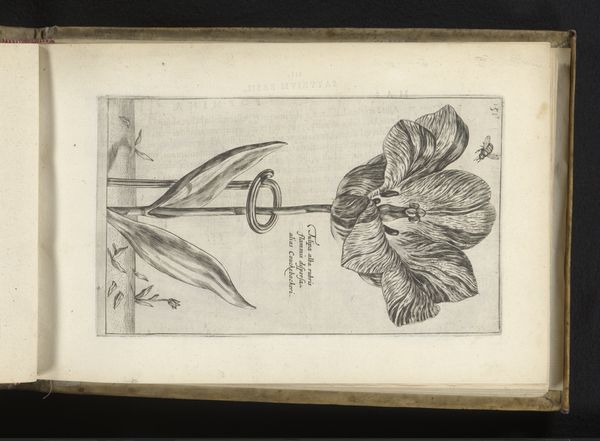

drawing, paper, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

flower

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 210 mm, width 136 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

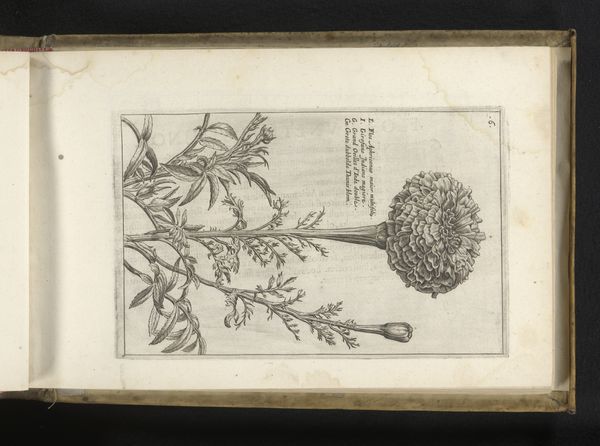

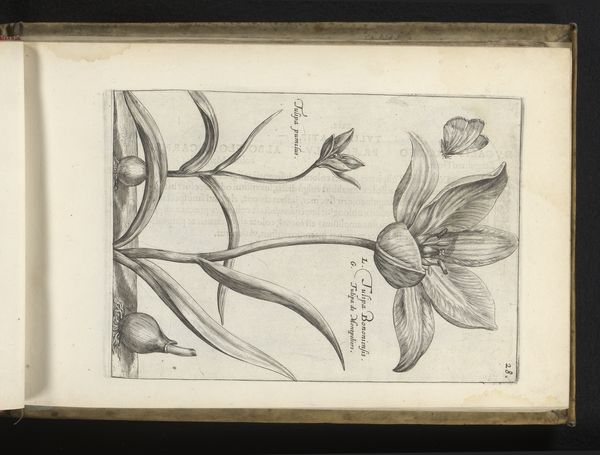

Curator: Look at this delicate image—a drawing titled Afrikaantje (Tagetes), dating back to 1617. It’s held here at the Rijksmuseum and was created by Crispijn van de Passe the Younger. Editor: There's an appealing coolness about it, isn't there? The monochromatic palette focuses my eye immediately on the texture. I’m noticing the subtle lines used to render light on each leaf and petal, and I'm appreciating the way ink interacts with the paper grain. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the socio-political context: a time of burgeoning global trade, and expanding botanical knowledge. Van de Passe captures this flower, an exotic newcomer, not simply as an object of beauty but as a symbol of burgeoning cultural exchange. It prompts us to ask—who had access to these plants and what did they signify about status and knowledge? Editor: Good point. Thinking about the production of this print: it would have been produced using etching, a precise, time-consuming craft. The materials—the copperplate, inks, and paper—speak to a whole economy around printmaking, to a community of artisans and printers that distributed images. Who purchased it, how was it used, how were these prints circulated? Curator: And note the careful rendering of the Afrikaantje, also known as a Marigold. While presented with scientific precision, its prominent display elevates the plant. It becomes a subject worthy of aesthetic contemplation, mirroring the rising interest in natural history during the Renaissance. Editor: The presence of the bee amplifies that scientific curiosity. It provides scale but also implies observation. The materiality of the final drawing represents the culmination of many processes. Consider that it all results in multiple reproducible images to be traded, resold, colored, displayed, and so on! Curator: It is an amazing piece of history! The image represents something much larger. The print becomes a meeting point for art, science, trade and politics of the 17th century, revealing the plant as a potent emblem of the era's shifting cultural landscape. Editor: I agree. From its materiality, labor to the subject, the flower’s story goes beyond just pigment and paper to the wider world.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.