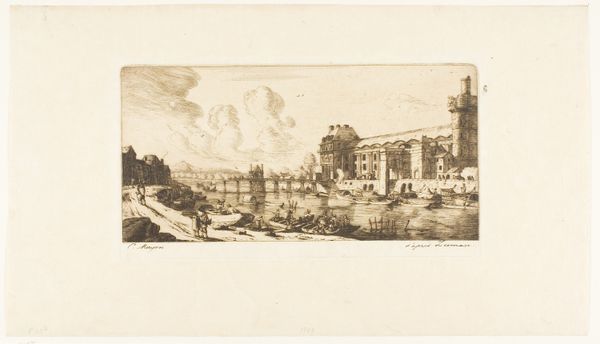

Gezicht op het weeshuis van Berlijn, gezien vanaf de Strehlow-poort 1749 - 1808

0:00

0:00

johanngeorgrosenberg

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 487 mm, width 735 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I find myself captivated by the somber atmosphere conveyed in Johann Georg Rosenberg's engraving, "View of the Orphanage of Berlin, Seen from the Strehlow Gate." There's a muted quality to it. Editor: Indeed, the quiet industry of this cityscape almost belies the supposed Neoclassical embrace of order and reason, doesn't it? What statements do you feel it's trying to make? Curator: Well, first and foremost it seems preoccupied with place—with the weight of institutional structures. But more than that, I detect an odd melancholy. The delicate linework renders the architecture in precise detail, yet there's a stillness that settles like dust, an inescapable loneliness even amid communal existence. Editor: Precisely! And consider the positioning of the orphanage itself, visible, but across the water. The Strehlow Gate and the boats become these thresholds, these sites of constant transit and transaction—and the etching seems to ponder the social positionality of orphans in relation to labor. Are they part of it? Set apart from it? Made invisible within it? Curator: Invisible, perhaps, until the boats bring them lumber for the fire... See, to me, it’s the light—or lack thereof—that gives the whole composition such depth. The way it softly illuminates the buildings creates the same kind of shadows, real and symbolic, you'd see hovering inside that very building! Editor: I agree, and perhaps that shadow points to the inherent tensions in depicting this kind of institution. The formal qualities may lean into that popular “picturesque” aesthetic, but beneath that charming surface, there are always sociopolitical forces churning and at play. Curator: As an artist, that makes sense, doesn’t it? Because the "truth" lies as much in the dark crevices as in the stark illumination. This cityscape manages to embrace both with such understated beauty, which gives it an appeal outside the bounds of historical data! Editor: Understated is a key term here. And I’d say that’s why an image made at this time in history can speak to us today, across generations. Articulating social precarity while still insisting on aesthetic detail—not everyone can achieve that balance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.