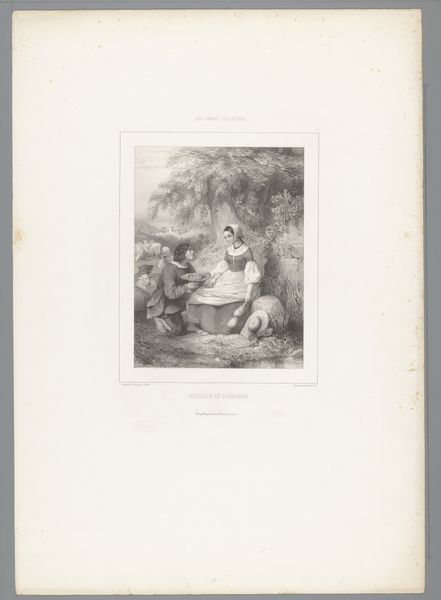

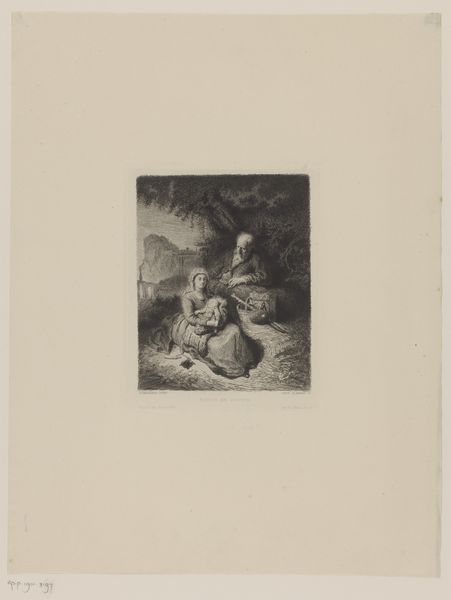

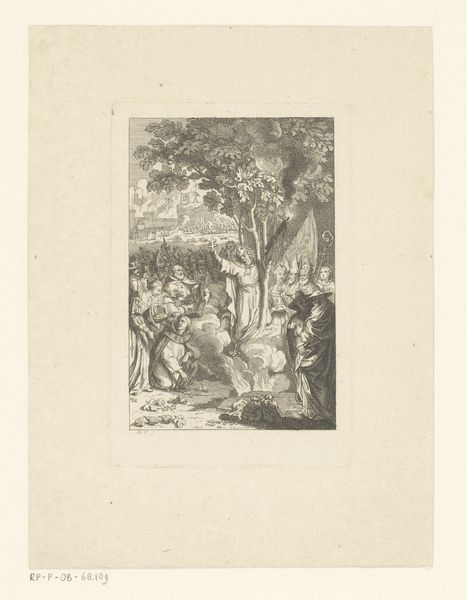

Vrouw, twee kinderen en lezende man picknicken bij een boom 1843 - 1845

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

book

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 396 mm, width 288 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Ah, what a pastoral scene! We're looking at "Vrouw, twee kinderen en lezende man picknicken bij een boom"—that is, "Woman, Two Children and a Reading Man Picnicking by a Tree." It's an etching and drawing by Camille-Joseph-Etienne Roqueplan, dating back to between 1843 and 1845. It just exudes tranquility, doesn't it? Editor: Tranquility… yes, but also the overwhelming burden of leisure. The labor that made this picnic possible, both visible and invisible, is on my mind right away. Who washed those clothes? Who prepared the food they’re so casually enjoying? Curator: I suppose one could see it that way. But look at the textures Roqueplan achieves with simple lines! The foliage is alive, almost shimmering. And that light dappling through the trees—it pulls you right in. I can almost smell the earth. Editor: It’s undeniably skilled draftsmanship, but that “smell of the earth” probably included a hefty dose of class division. Etching allowed for reproduction and wider distribution. These images romanticized country life for urban audiences, obscuring rural realities like poverty and back-breaking farm labor. Curator: Perhaps, but isn't there a simpler reading? A father reading aloud, the mother attending to the children. There's a shared experience happening here, fostered by art and literature in a peaceful setting. Editor: Shared for *whom*, though? This idealized version of leisure depended on the exploitation of land and labor, concretized in materials – the paper, the ink, the very book that the father reads from. How were these things produced and distributed, and who bore the costs? Curator: You certainly bring an… earthier perspective, let’s say. For me, it whispers of stories. Of connection to nature and to each other. But it's true, that these visions also masked complex social tensions in those times. Editor: Art often provides more answers when you analyze what's literally in front of you and the implications of its existence. Considering who possessed the ability to depict these scenes versus who was unable to depict these same circumstances in their lives. Curator: It’s funny, isn't it? How an image can hold so much—light and shadow, tranquility and tension—all at once. And that the most important component to it, is us. Editor: Absolutely. The labor that went into its making, the values it upholds, the eyes of its viewers...that makes it meaningful.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.