![[Minaret of the Chief Mosque at Damghan, 1026–1029] by Luigi Pesce](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2ZkYjgyNzlmLWVhOGYtNDY4ZC05MWVlLWQ1MDNjZWRkMzBjOC9mZGI4Mjc5Zi1lYThmLTQ2OGQtOTFlZS1kNTAzY2VkZDMwYzhfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

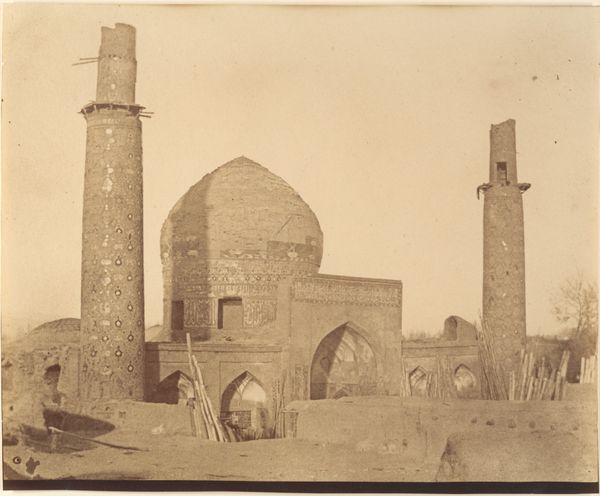

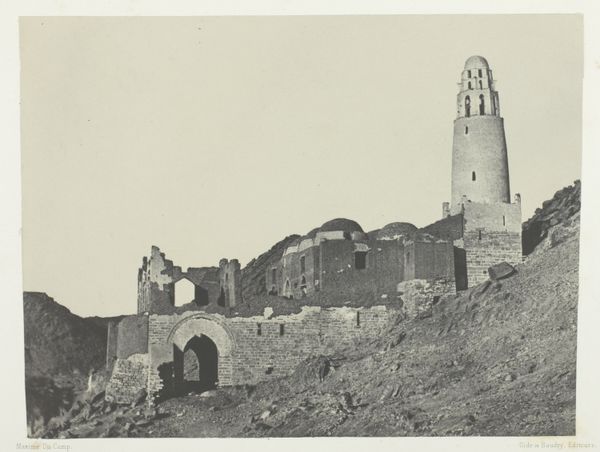

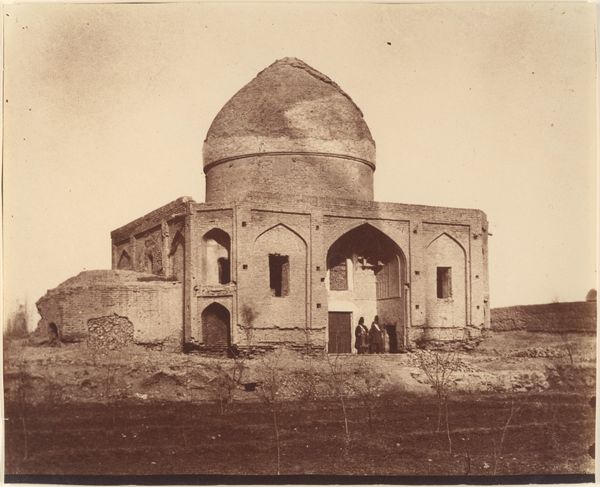

[Minaret of the Chief Mosque at Damghan, 1026–1029] 1840 - 1869

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography, site-specific, architecture

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

site-specific

#

islamic-art

#

watercolor

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this striking image, "[Minaret of the Chief Mosque at Damghan, 1026–1029]," captured sometime between 1840 and 1869 by Luigi Pesce, shows a towering minaret and adjacent ruined structures, a haunting scene rendered in a daguerreotype. What a powerful depiction of time and history. How do you read the socio-political implications of showcasing such a ruin? Curator: It's intriguing, isn't it? A mid-19th century Western artist framing a piece of Islamic architecture not as a symbol of power or exotic otherness, but almost as a memento mori. We see this subject depicted at the cusp of modernity. What choices were made in framing the scene and the viewpoint selection, and for what reasons? I am curious what this photograph represented for its original Western audience, and what narratives about cultural dominance it reinforced, or challenged. Editor: That makes me consider what it means to document decay. Was it a form of, dare I say, visual colonialism, freezing a moment of perceived decline? Or did it reflect a genuine fascination with preserving a disappearing past? Curator: Both could be true! The photographer presents the minaret, which was part of a functioning religious and social complex, as isolated. What impact did the photographer have, then, as a selective narrator shaping the view and legacy of a culture’s artifacts, within an emerging visual medium of that time? And it leads us to think: How did images like this influence or create biases within art history itself? Editor: That's fascinating. It changes the way I see the image, from a simple historical record to a layered statement about power, perception, and the very act of documenting history. Thank you! Curator: Precisely. Art isn’t made in a vacuum, and these images reflect power dynamics. Looking at the image with the lens of social context opens up fascinating conversations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.