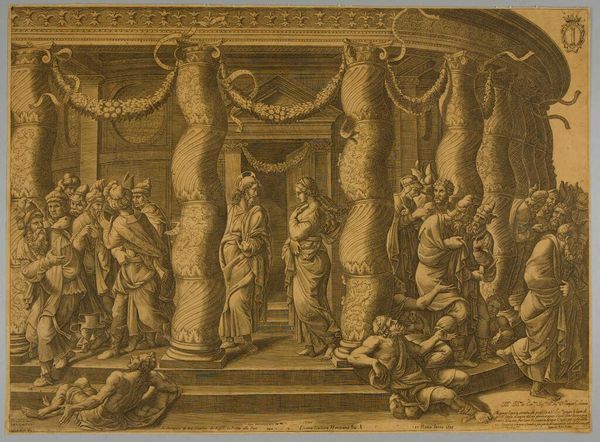

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

caricature

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 436 mm, width 576 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

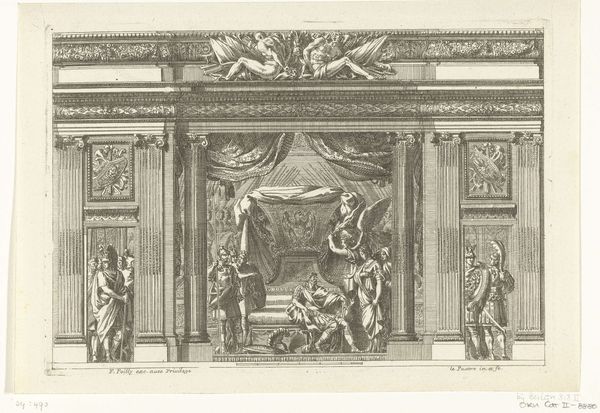

Curator: Look at the composition, the textures rendered in the print – Elisha Kirkall’s engraving, made in 1722, depicting Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery. Editor: The mood feels subdued, even melancholic. It's a scene filled with tension, but the monochromatic rendering dampens any sense of immediacy, any danger. Curator: The technique is really something. Note how Kirkall simulates tone through intricate lines and patterns of the engraving itself. This engraving would have allowed wider access to religious subject matter, creating almost mass produced access for domestic settings. Consider what this distribution facilitated! Editor: Yes, the wider distribution speaks volumes. What strikes me is how the artist uses symbolism to underscore the woman’s plight and the compassion of Christ. Observe how the figures on the periphery are shrouded in shadow. This recalls earlier images and functions to contrast with Christ’s brilliantly lit form. Notice also the bowed heads—of those scribes, elders perhaps—reflecting guilt, shame or simply the weight of the law. The psychological dimension is palpable. Curator: Exactly! The story itself – Christ challenging the accusatory mob – gains different resonances, though. Was this piece commissioned? For a wealthy patron, or as an exercise in production? The answer might affect my interpretation. Editor: Context indeed, but let’s consider also how viewers over time might interpret the image and its use of figures from history or art traditions! The columns almost writhe as though nature cannot hold this solid construct still, or that moral strictures will continue to shift. Perhaps not as comforting as a patron might expect. Curator: You are looking at something enduring, whereas I think the print medium enabled more accessible conversations, for a new patron-base, where morality might indeed be in question. Editor: In essence, the scene and composition encourage reflection on culpability, judgment, and ultimately, redemption. And the print carries that meaning through time, shifting ever so slightly, until we, here, stand reflecting on it today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.