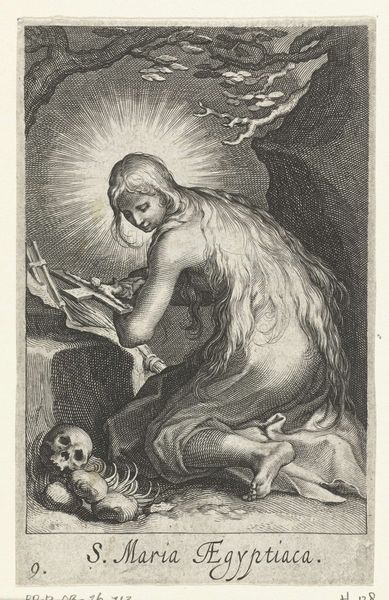

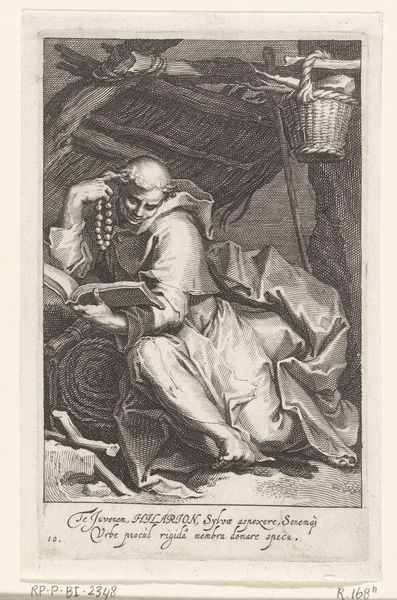

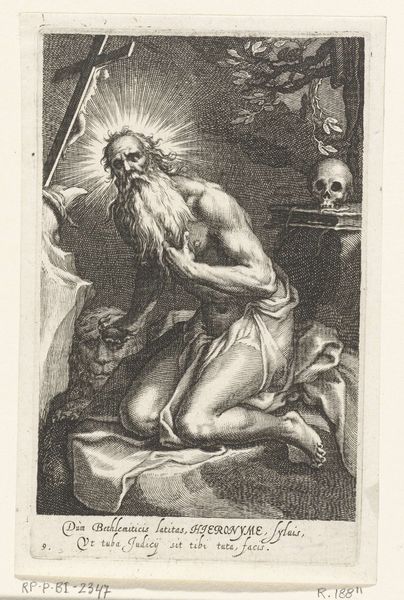

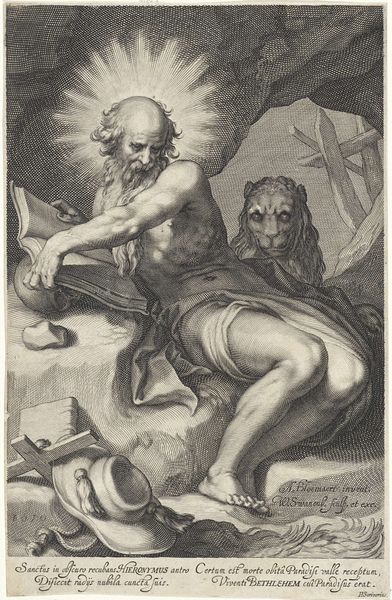

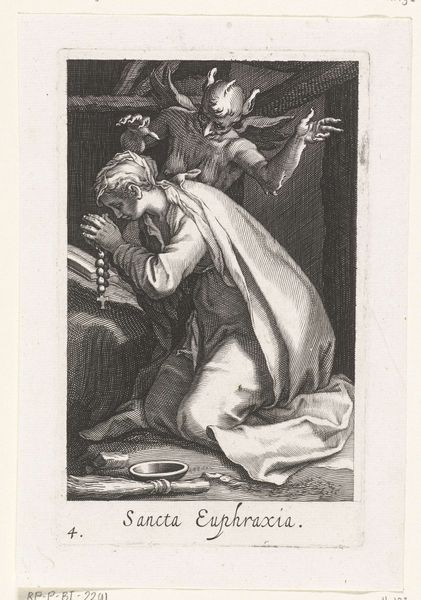

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

vanitas

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 145 mm, width 90 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Saint James of Nisibis as a Hermit" by Boëtius Adamsz. Bolswert, made sometime between 1590 and 1612. It's an engraving. The detail is really striking; the way he rendered the texture of the fabrics is so impressive. What do you see when you look at this work? Curator: I see the socio-economic structures of image production at play. This isn’t just a devotional image; it's a commodity. The printmaking process – the labor of the engraver, the availability of materials like the metal plate and the ink – determined its very existence. Editor: A commodity? Curator: Yes. Think about the role of printmaking in early modern Europe. It democratized images, making them accessible to a wider audience. It speaks to the rise of a market for religious imagery, catering to different social classes and devotional practices. Who was consuming these images, and what need did they fulfill? Editor: That's interesting. So, the act of creating multiple copies changes the meaning of the artwork itself? Curator: Precisely. The material conditions – the repeatable nature of the engraving process – allowed this image to circulate, reaching beyond the elite circles who could afford unique paintings. Also, look closely at the symbolic tools like the skull and crucifix; they speak volumes about the dominant culture. This isn't just devotion; it's manufactured devotion intended for a mass audience. Editor: I see. So the act of engraving transforms a potentially singular religious experience into a commercially available object. It’s fascinating how much we can infer from simply considering the materials and means of production. Curator: Indeed. Examining the 'how' and 'why' it was made unveils a wealth of information about its social and economic function.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.