drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

german-expressionism

#

figuration

#

expressionism

#

monochrome

Copyright: Public Domain

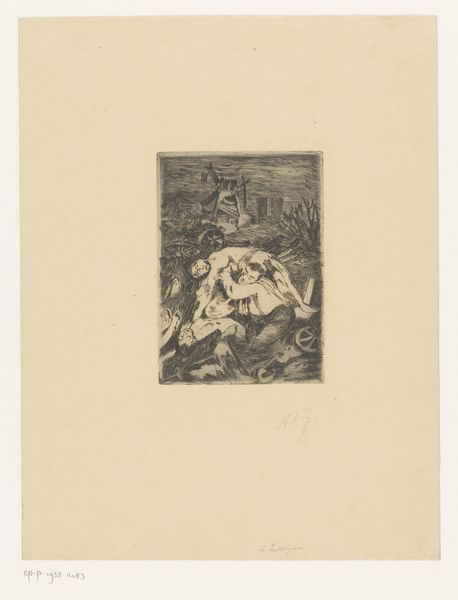

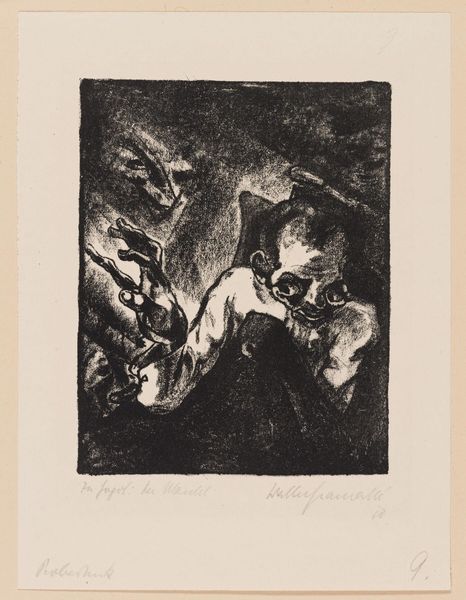

Curator: What a powerfully bleak etching. “Die Totenklage,” or “Lament for the Dead,” created between 1921 and 1922 by Lovis Corinth, offers a raw, immediate encounter with grief. Editor: That sums it up, raw is the word. It feels…claustrophobic, doesn’t it? The figures are so close together, almost intertwined, like they're suffocating under the weight of their sorrow. It's unsettling, and almost a bit triggering if I'm honest. Curator: Corinth’s expressionistic style amplifies that emotional intensity. The chaotic lines, the stark monochrome—it pushes the scene beyond simple representation into a space of visceral feeling. He made this rather late in life, didn't he, already a well-regarded member of the Berlin Secession? But moving into such a dark, intimate sphere... Editor: You know, it almost feels like a fragment of a nightmare rendered in ink. I mean, look at how indistinct some of the faces are. Is that a body slumped in the foreground, or are they all supporting a limp figure between them? It makes you feel like you shouldn't be looking; it's a voyeuristic intimacy. The marks made in the etching almost claw at your eyeballs. Curator: The choice of etching emphasizes that intimacy. The lines have a fragility that resonates with the vulnerability of mourning. Remember that etching, as a printmaking process, allowed Corinth to replicate and disseminate the work, thus turning personal grief into a shared experience of collective lament. It could suggest how trauma echoes through communities. Editor: You make it sound almost altruistic, making trauma something people can share...but grief like that feels intensely private to me. Curator: It can be both, I think. Corinth offers not just an image of sadness, but a space for recognition. Art often occupies this strange position as an opportunity to look, when normally that act of witnessing would be intrusive, or unhelpful. Editor: I suppose you're right. We wouldn't be looking at it otherwise, would we? Well, regardless, I’m left feeling profoundly uneasy and affected. Corinth really gets under your skin with this piece. Curator: Exactly, the beauty of the mark is its ability to reach beyond time and context to meet someone directly where they are. Even a hundred years on.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.