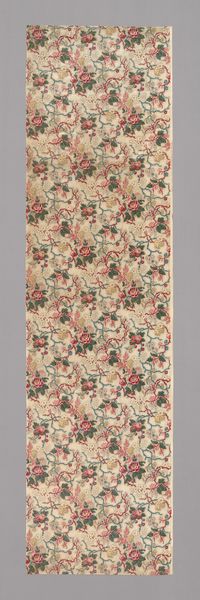

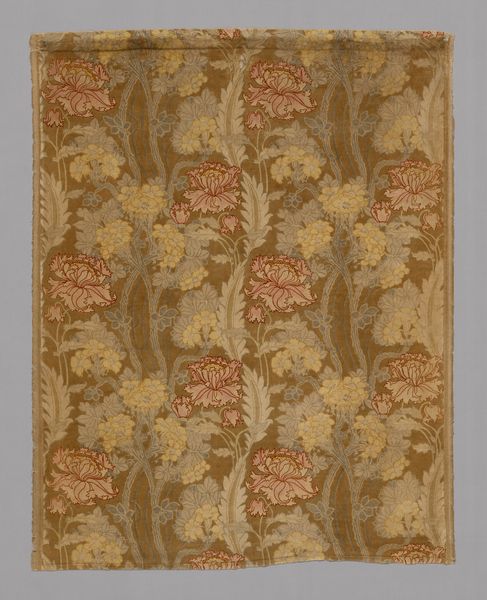

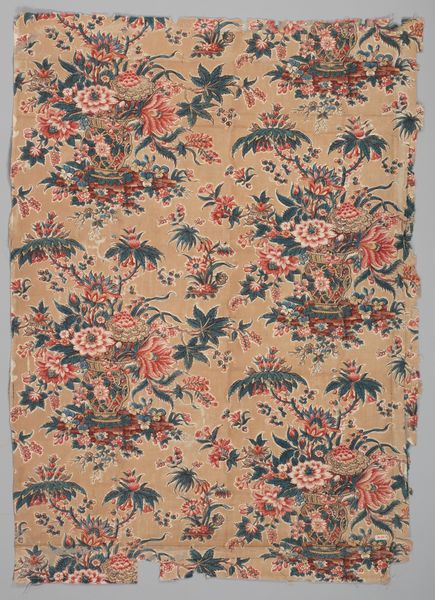

Dimensions: 173.7 × 81.7 cm (68 3/8 × 32 1/8 in.) Repeat: 31.3 × 40.2 cm (12 3/8 × 15 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have a "Length of Printed Fabric" originating from the Oberkampf Manufactory around the 1780s, a remarkable piece of textile design housed here at the Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: My first impression is one of muted elegance. It’s densely patterned, but the restrained color palette gives it a calming feel, almost like a faded tapestry found in an old manor. Curator: Absolutely, the muted tones are characteristic of the period, and this piece offers insight into the burgeoning textile industry of the late 18th century and its global networks of trade and consumption. The Oberkampf Manufactory, you see, played a crucial role in the industrial revolution. Editor: Textiles, especially printed ones, became potent symbols of status and cultural exchange during this period. How might this particular design reflect or subvert the norms of its time regarding gender or class? Curator: Considering the period's prevailing power structures, it's essential to remember that while textiles like this might appear benign, they were enmeshed in exploitative colonial practices and slave labor necessary for raw material extraction like cotton. Furthermore, the designs often catered to elite tastes, reinforcing existing social hierarchies, as it was mostly traded and acquired in Europe and America. Editor: The repetitive floral motifs strike me as interesting from a feminist perspective. Patterns historically relegated to domestic spheres are being industrialized and commodified. Was this textile purely ornamental, or did it serve a practical purpose? Did women and other minorities have ownership of similar manufacture work? Curator: While undoubtedly decorative, these lengths of fabric would be fashioned into clothing, curtains, and upholstery, saturating elite domestic spaces and reinforcing class distinctions. While wealthy women might be consumers, it is more relevant to emphasize that mostly only European men were able to own factories at the time. Therefore it served to extend a certain class power. Editor: Knowing all of this imbues the fabric with greater meaning, and it raises crucial questions about aesthetics and politics of design. We must approach such objects acknowledging that they can often perpetuate injustice while also displaying intricate skill and detail. Curator: I agree, and placing such artworks within a broader history of production, trade, and consumption helps us comprehend their profound impact, both intended and unintended. It demonstrates how art, even seemingly "minor" art like fabric, is interwoven with socio-political dynamics. Editor: Exactly, thank you for unveiling those deeper textures for us! Curator: It's been my pleasure; now it's your turn to delve further.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.