![Niccolo Orsini, 1442-1510, Count of Pitigliano and Nola, Captain of the Army of the Roman Church and of the Florentine Republic [obverse] by Caradosso Foppa](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2ZiYzJkMGNhLWFkMzgtNDU4My05MDM2LTk2ODBiOGZiMWE1MC9mYmMyZDBjYS1hZDM4LTQ1ODMtOTAzNi05NjgwYjhmYjFhNTBfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

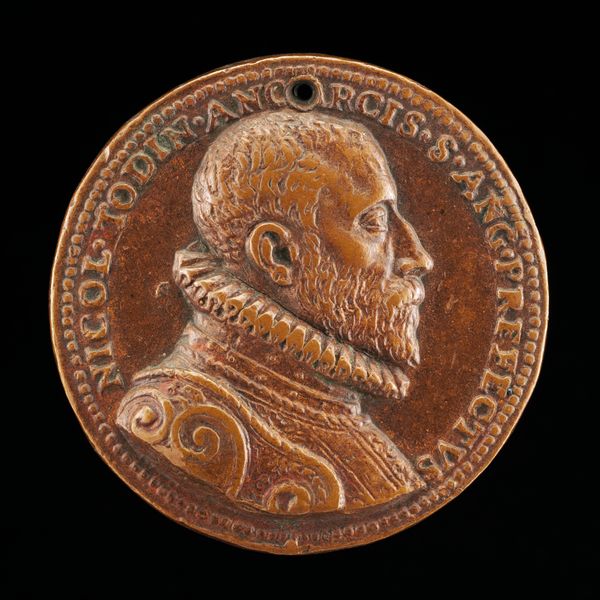

Niccolo Orsini, 1442-1510, Count of Pitigliano and Nola, Captain of the Army of the Roman Church and of the Florentine Republic [obverse] 1485 - 1495

0:00

0:00

bronze, sculpture

#

portrait

#

sculpture

#

bronze

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: overall (diameter): 4.25 cm (1 11/16 in.) gross weight: 30.73 gr (0.068 lb.) axis: 6:00

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Standing before us is a bronze portrait medal depicting Niccolo Orsini, Count of Pitigliano and Nola, crafted by Caradosso Foppa between 1485 and 1495. It’s a striking example of Italian Renaissance portraiture. Editor: It has a certain stern quality, doesn’t it? The metal gives a weightiness to Orsini’s image, a sense of permanence and authority. His gaze is fixed and rather imposing. Curator: Exactly. And consider the method Foppa employed—bronze casting, an intricate process requiring skilled labor. It speaks to the wealth and status required not only to commission such a piece but to actually produce it. Editor: This portrait reflects Niccolo's importance and how that impacted Renaissance social structure and power relations, I think. The inscription around the edges highlights his titles "Captain of the Army of the Roman Church," further emphasizing his roles within those political frameworks. How complicit was the creation of art with power and masculinity in this period? Curator: That's a valid point to think about. Bronze itself signifies something: military strength, durability, and ultimately, value. The circular format, mimicking a coin, even suggests a system of exchange or perhaps currency. The fine details – the texture of his armor, the curve of his brow – underscore Foppa's expertise. Editor: I notice he’s depicted in profile which, for me, connects it to ideas about representation and idealisation in Ancient Greece and Rome. What statement is being made about what leadership and even the patriarchy itself stands for through this sort of aesthetic? Curator: Good observation. The classical allusion, prevalent during the Renaissance, certainly adds layers to our interpretation. Now, about the labor—it’s a multistep undertaking: creating the mold, casting the bronze, and the fine chiseling after removal. There were whole workshops involved here. This wasn't the work of a solitary genius. Editor: Absolutely, recognizing that system of labour dismantles certain myths surrounding artistic production at the time. The "solitary genius" narrative has tended to erase those collective, yet stratified production contexts. Curator: The interplay between the historical figure, the artistic medium, and production means gives such insight. Each decision reveals the context of the social moment and what was happening there. Editor: And perhaps it also prompts reflections on our own current cultural frameworks – who are the leaders and 'icons' celebrated now, and how will we remember our present era in the future?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.