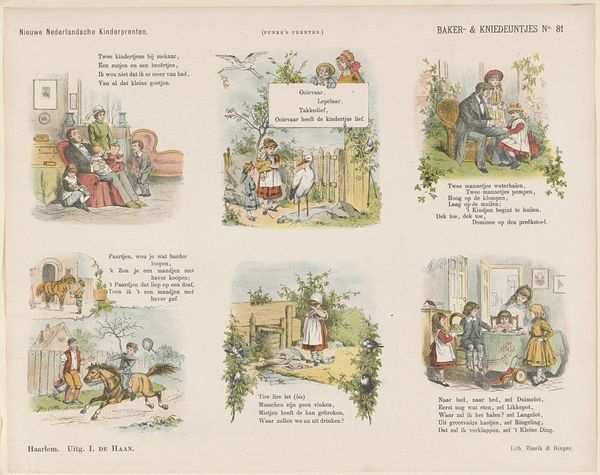

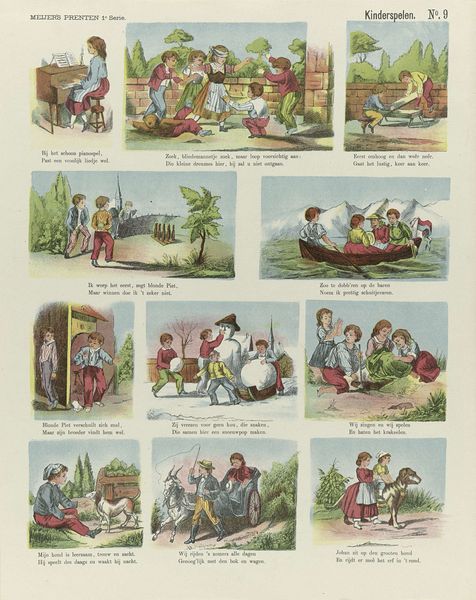

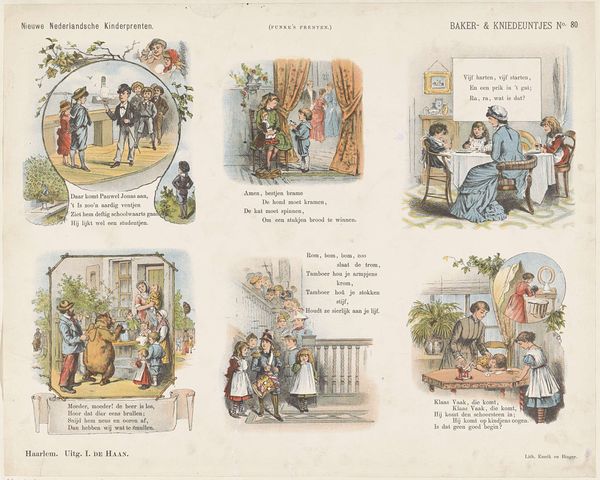

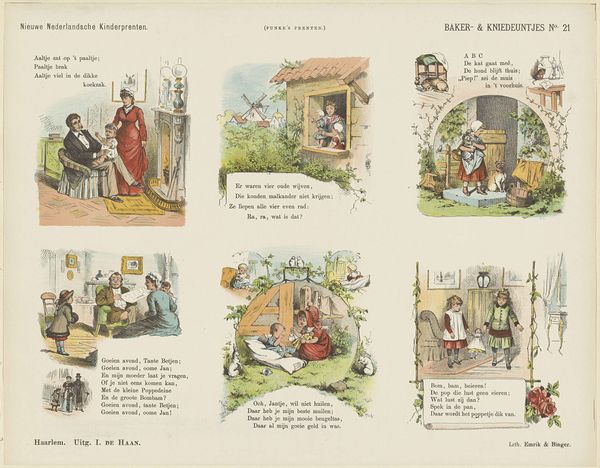

print, paper, pencil

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

paper

#

folk-art

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

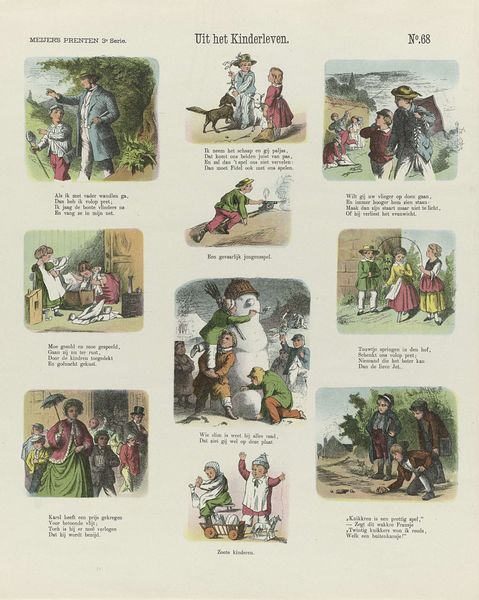

Dimensions: height 345 mm, width 440 mm

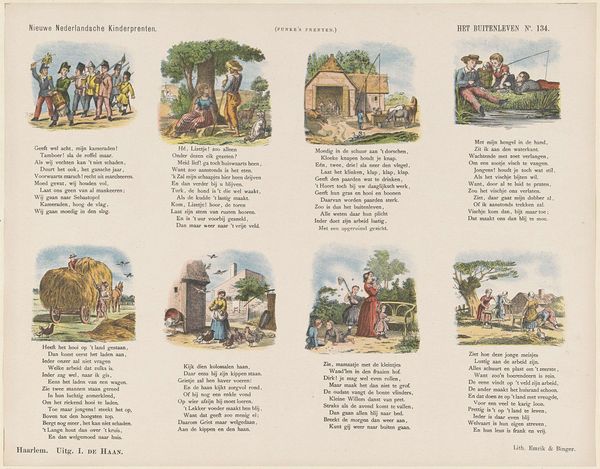

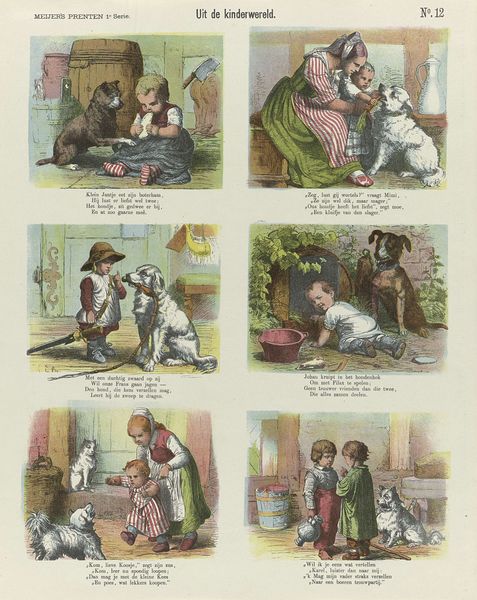

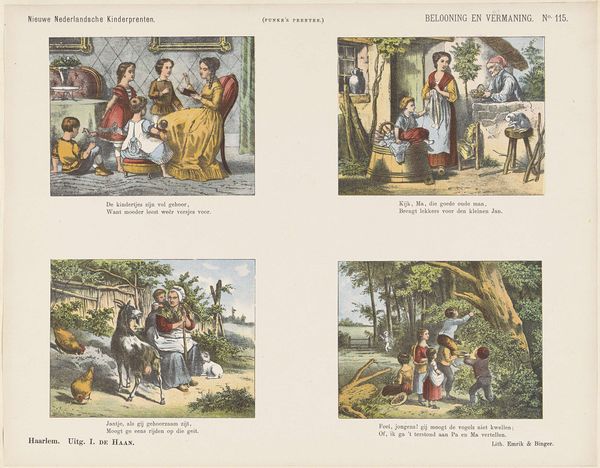

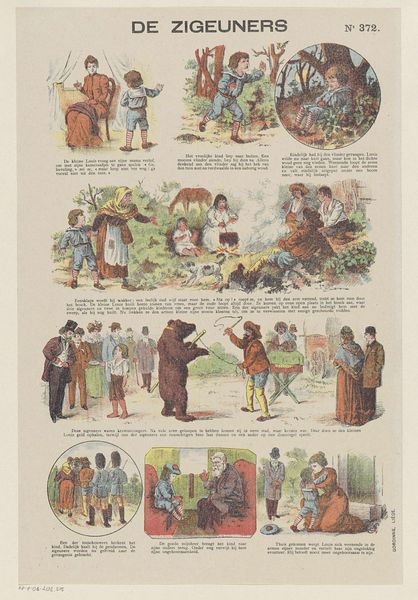

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

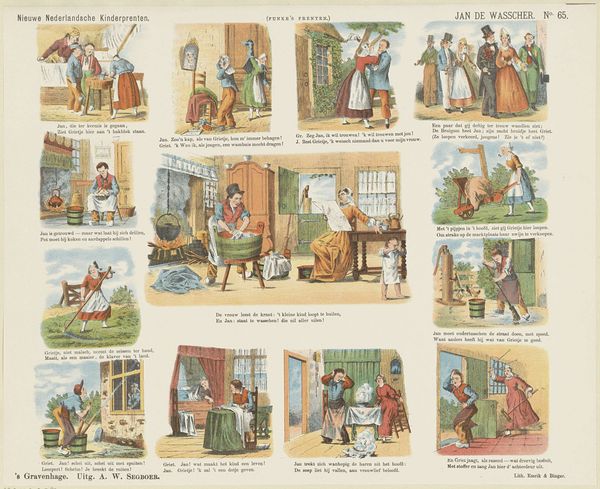

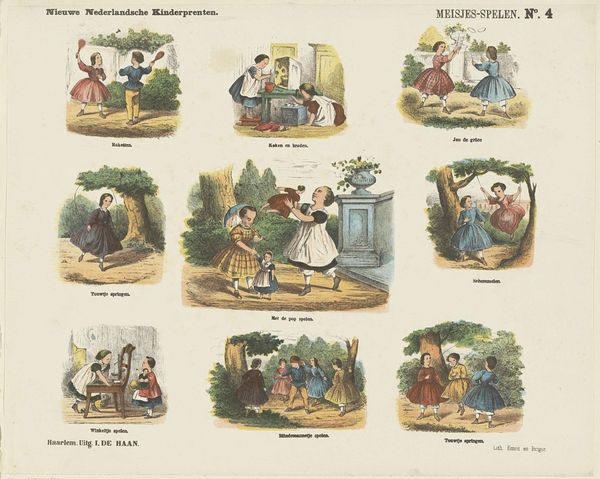

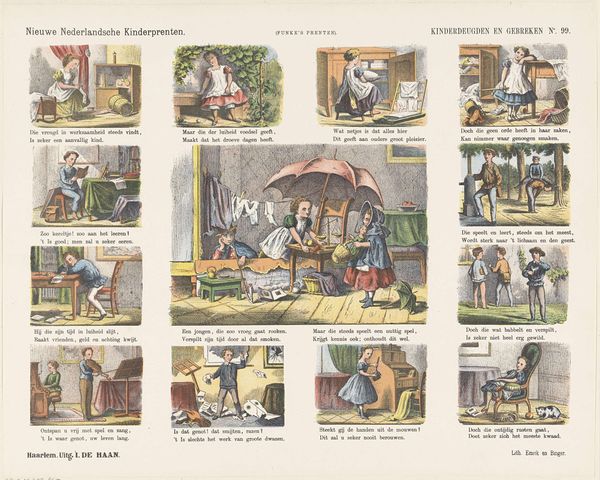

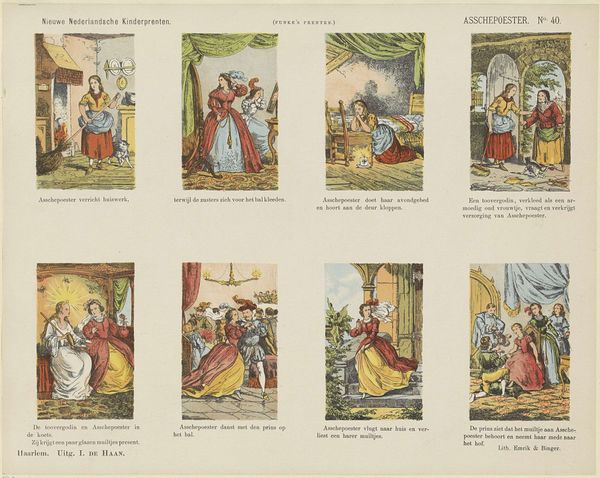

Curator: This print is titled "Baker- en kniedeuntjes", which translates roughly to "Bakers and Nursery Rhymes." It was created sometime between 1875 and 1903 by Jan de Haan. It's a children's print combining image and text. What’s your first take on it? Editor: Oh, wow, it’s… nostalgic! It reminds me of old-fashioned storybooks, but somehow more innocent? The soft colors and little vignettes feel so comforting, like a peek into a simpler, if somewhat idealized, world. It’s got a quaint charm that’s hard to resist. Curator: I agree. There is a lot of social context embedded here. These were meant for mass consumption as inexpensive teaching and educational material and represent childhood themes in late 19th-century Netherlands. We see snippets of children’s games, domestic scenes, and popular rhymes of the era. It reflects the social values being instilled at that time. Editor: The rhymes really do ground the image. They seem like simple observations, little lessons couched in play. Take the one with the rose for a grumpy mood… it’s so sweet and instantly accessible. And then you realize these everyday scenes—playing, baking—are really important components of childhood learning and tradition. Curator: Absolutely, it offers us insights into the dynamics of community life, gendered expectations and class distinctions of the time, all viewed through a pedagogical lens meant for young children. For instance, we see clear divisions in gender roles portrayed in several panels. The visual repetition also helped solidify the rhymes for better memorization and instruction. Editor: Thinking about it more critically, I see the darker sides. It's quaint but these prints subtly reinforce societal expectations, confining children—particularly girls—to domestic roles. Curator: Precisely. The imagery normalizes a very specific worldview, one we now view through a more critical lens of race, gender, and class awareness. What was considered charming at the time may carry undertones of indoctrination and exclusion by today’s standards. Editor: Well, regardless, there’s still something very tender and universally human about it, and about observing the echoes of time—which makes it fascinating to consider in a modern context. Curator: Yes, by viewing through these contexts, we get to not just see the sweetness but understand the forces shaping that era’s understanding of childhood and social order, that informs who we are today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.