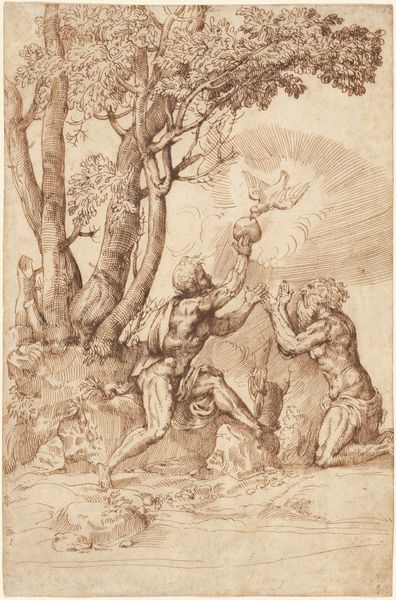

print, engraving

# print

#

pen sketch

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 247 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. Here at the Rijksmuseum, we’re standing before Battista Franco’s engraving, "The Rape of Deianira," created sometime between 1520 and 1561. Editor: My first impression is a sense of frantic energy. The line work, though delicate, creates a real feeling of movement. Look at the centaur, his posture, the way he is positioned, seemingly bursting out from the landscape, contrasted to the detailed etching of the landscape elements which surround it. Curator: Absolutely. Considering Franco's printmaking technique, the engraving medium would have demanded skilled labor and specific tools. The act of incising lines into the metal plate and then using that plate to reproduce this scene speaks to the wider accessibility of images during the Renaissance. Think of the print not just as art, but as a reproducible commodity. Editor: And the myth itself—the rape of Deianira by the centaur Nessus—carries immense symbolic weight. It is a primal scene about unchecked male desire, violation, and the vulnerability of women. It's disturbing to think how readily this narrative, and its underlying ideology of domination, circulated. Curator: Precisely. The reproductive nature of printmaking allowed for wider dissemination of those ideologies. Notice the centaur’s muscular physique and Deianira’s contrapposto pose. It calls attention to their power dynamics, yes, but how might this print, through its composition, invite viewers to, if not condemn then consider their position in this encounter. It almost asks, what action do we take? Editor: True. And this imagery certainly links back to older visual traditions, particularly classical sculpture and vase painting. Franco positions the players, figures from antiquity in poses that nod to classical antiquity, re-performing older cultural narratives to which people reading his prints would have an indexical association. I also consider its implications in gendered and patriarchal structures as it may function for a modern viewer, it becomes fraught with symbolism surrounding victimhood and toxic masculinity. Curator: Interesting thought, how that shift would have occurred, due to, of course, modern interpretations, not possible during its conception. In conclusion, by analyzing Franco’s work through material production and its relation to a long visual history, we can unlock critical social commentary on this era. Editor: It definitely leaves a lingering unease and many complex layers of understanding regarding historical narratives surrounding vulnerability and power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.