drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

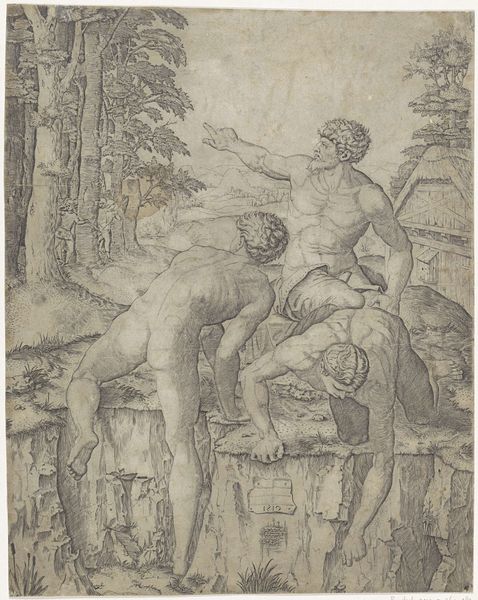

Editor: Here we have Hendrick Goltzius' "Jupiter and Europa" from around 1590, done in ink. The tones create a serene but dramatic effect... What catches your eye about this drawing? Curator: The image speaks volumes about the power dynamics and socio-political interpretations of classical mythology in the late 16th century. We're seeing not just a depiction of a mythological event, but a commentary on authority, seduction, and perhaps even the nascent development of naturalism as a means of understanding the world around us. What do you notice about the landscape, for example? Editor: Well, it feels very classical, very idealized. Distant mountains, a gnarled tree... is that a city in the distance? Curator: Exactly. And consider that detail in relation to the embracing figures. The rendering of their bodies – their sensuality – it's not just about aesthetics. This eroticism functions in conversation with the broader political sphere of the time. Consider also the gaze directed outward and upward, like she’s glancing towards the heavens… Editor: So, are you saying that mythological scenes like this weren't just pretty pictures? They carried real weight in terms of how people understood power and their place in the world? Curator: Precisely. The popularity of these mythological subjects served as a crucial vehicle for the Renaissance elites, as they were subtly making a claim to a noble lineage while justifying present realities and social constructs. And the printing press enabled wide dissemination of imagery, meaning such ideology could propagate into middle and even lower classes. What implications could arise when the divine intersects and legitimizes earthly power, shall we say? Editor: That's fascinating. I’d always looked at the beautiful landscape, and the embracing figures in "Jupiter and Europa", without considering the power and control these narratives supported. I appreciate you bringing this historical view to the artwork. Curator: And I’m interested in your fresh view into how the artist shapes our contemporary views!

Comments

stadelmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

After his return from Italy in 1591, Goltzius increasingly concentrated on designing compositions which other engravers then realised for his publishing house. The two drawings obj. nos. 1792 Z and 1793 Z are examples of such designs. While Goltzius used the pen only sparsely for the outlines, he modelled the bodies with a brush and set delicate accents of light with white opaque paint. He did not draw the line structure of the engraving but created a tonal and painterly chiaroscuro effect with generous brush washes, which the engraver then had to transfer into the hatching patterns of the copperplate.The motifs of obj. nos. 1792 Z and 1793 Z belong to a series of four ""Loves of the Gods"". Here, Zeus (Jupiter), the father of the gods, is seen embracing the king's daughter Europa; in the background the god in the guise of a bull abducts the beautiful princess.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.