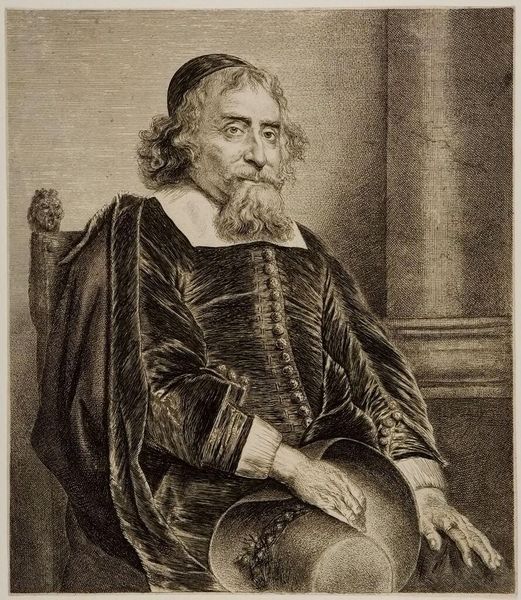

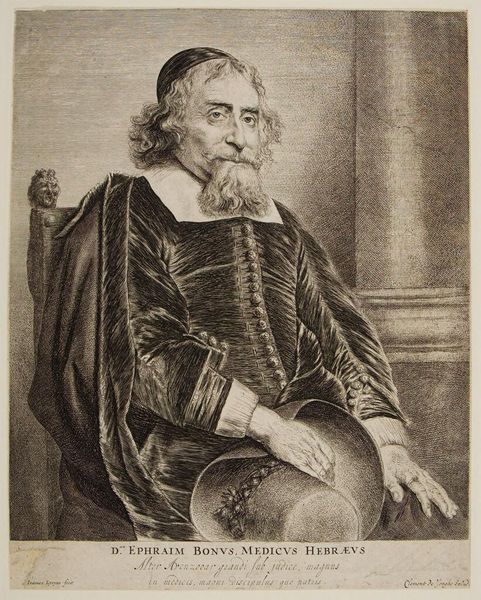

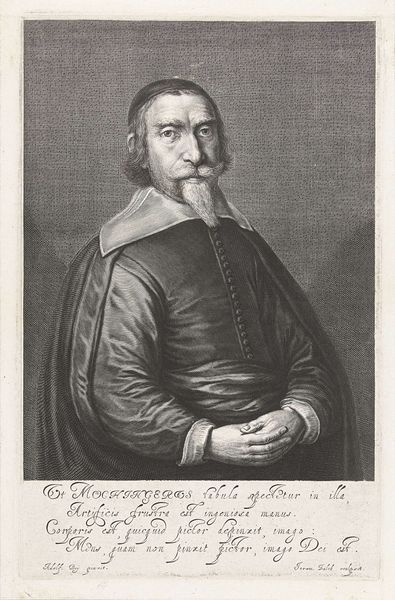

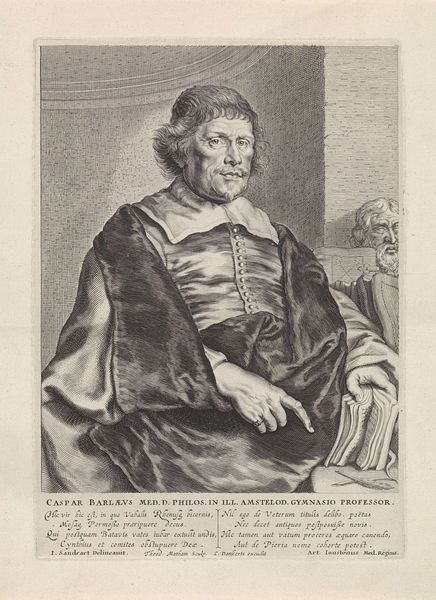

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

figuration

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 342 mm, width 271 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I find myself immediately drawn to the quiet dignity in this portrait. The subject appears self-assured, yet there is a certain pensiveness in his gaze. What do you see? Editor: The somberness of it is really striking; it's almost a melancholic scene despite the opulence. This work, created by Jan Lievens around 1640-1650, depicts Ephraim Bonus, and what's really interesting to me is its public role as a printed image at that time. Think of the accessibility! Curator: Indeed. Beyond the somber tone, the meticulous rendering of details like the beard, the fabric's texture, or even the slight glint in his eyes contributes so much. It goes beyond mere representation; Lievens uses those symbols to evoke intellectual weight and even a deep cultural heritage. Editor: Absolutely. Its distribution as a print—an engraving—meant it circulated within specific intellectual and perhaps even medical circles, reinforcing Bonus’s standing. How was Lievens, an artist who operated within very specific commercial and patronage networks, attempting to convey authority? The column in the background—what sort of social cue is provided through such a symbolic reference to classical antiquity? Curator: The column speaks to notions of strength and tradition, absolutely. It's part of the visual vocabulary to present Bonus as a figure of lasting importance, maybe tying him to lineages of wisdom extending into antiquity. Also note how light and shadow converge so intensely on his face. It elevates his knowing glance, as if he holds secret insights. Editor: Agreed, and think of the printing process at the time. The choices in tonality and the stark contrasts weren't just aesthetic. They allowed for clarity and readability when reproduced. So, it was very much about efficiently projecting the intended message onto the greatest number of people, bolstering the symbolic impact. Curator: I can almost hear the rustle of the paper, envision this piece being studied amongst scholars... Even now it projects an evocative authority. It underscores the power that images hold. Editor: Yes. Images weren’t simply decorative—they were actively shaping public perceptions and negotiating identities. Examining who and what was considered worthy of depiction in print is crucial. It brings me back to consider that we still grapple with representation and legacy-making in an equally image-saturated environment today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.