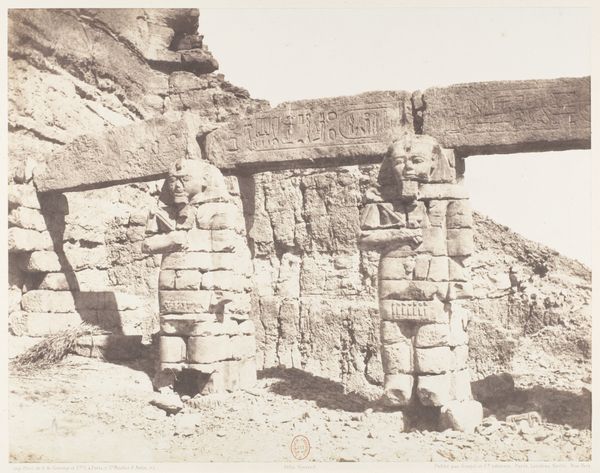

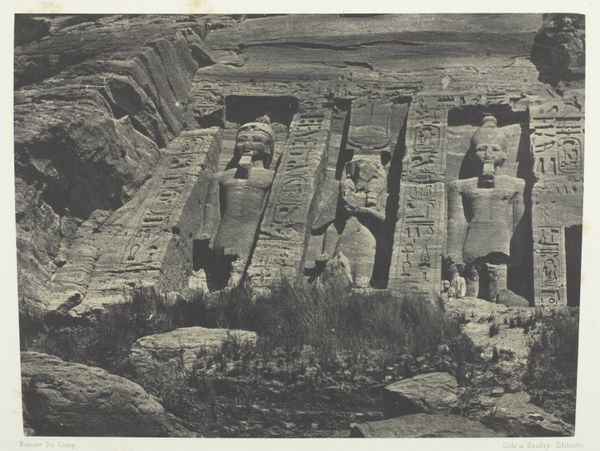

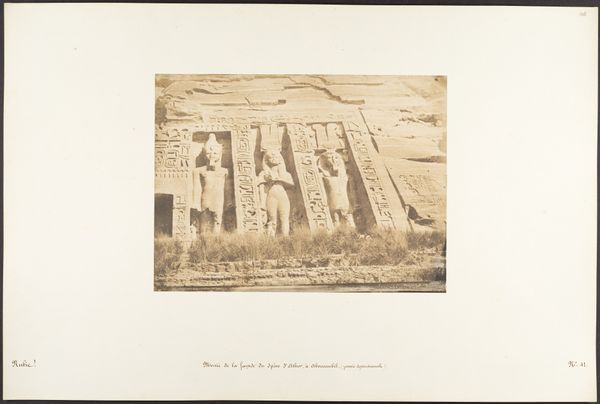

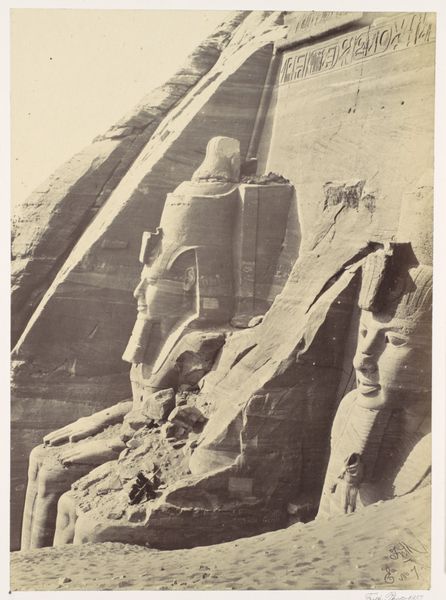

Ibsamboul, Vue Générale Du Grand Spéos De Phrè; Nubie Possibly 1849 - 1852

0:00

0:00

carving, print, etching, bronze, paper, photography, site-specific, gelatin-silver-print, marble

#

16_19th-century

#

carving

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

bronze

#

paper

#

photography

#

egypt

#

carved into stone

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

site-specific

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

france

#

marble

Dimensions: 16.5 × 21.7 cm (image/paper); 30.1 × 42.9 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

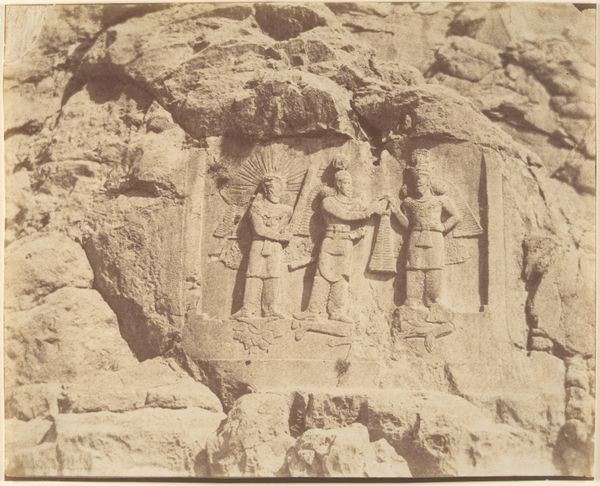

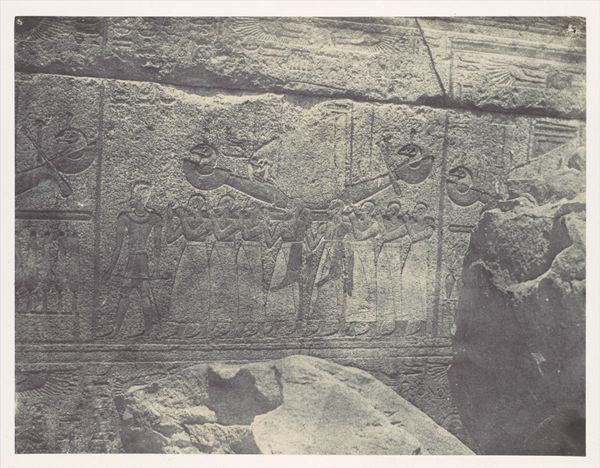

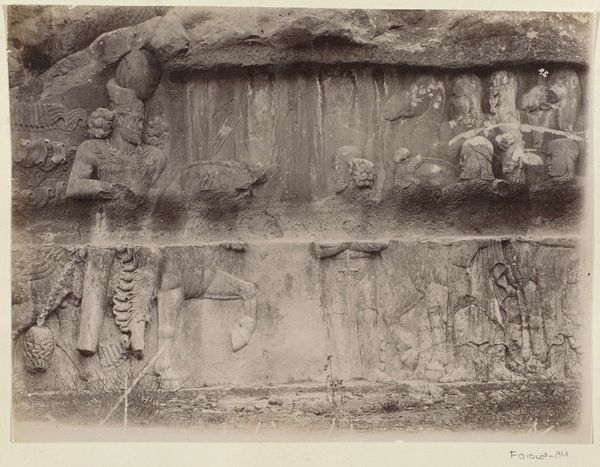

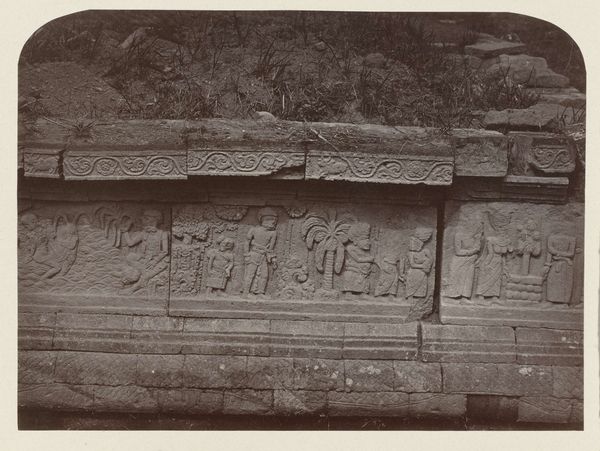

Curator: It's remarkable to gaze upon Maxime Du Camp’s “Ibsamboul, Vue Générale Du Grand Spéos De Phrè; Nubie,” a photograph taken possibly between 1849 and 1852. Editor: The sheer scale is what hits me first—these colossal faces emerging from the rock, silent witnesses staring across millennia. There's something both imposing and desolate about it. Curator: Absolutely. Du Camp captured this view of Abu Simbel during a pivotal time, a period of intense archaeological exploration in Egypt. This image documents a monument that testified to Ramses II’s power, which of course, links back to a deeply engrained narrative of divine kingship. It’s striking as a gelatin-silver print—the tonal range adds so much weight. Editor: The figures above also carry immense historical and cultural context, especially given the later intervention to save this ancient place. Do you believe that they were dwarfed in power over time? Curator: Yes. The removal project and later restoration, partly funded by the World Bank, highlighted both international cooperation, but also an imposed, western-dominated aesthetic. It forces a consideration of cultural value—whose heritage is being preserved, and why? The choice to present ancient culture to modern norms inevitably prompts scrutiny. Editor: It’s unsettling to ponder—like capturing lightning in a bottle, or trying to contain the ocean in a teacup. It really makes you think about the museum context. Photographs like Du Camp's shift their meaning over time. Initially records, now treasures in their own right. The politics of representation is really what is being framed. Curator: Exactly! It transforms what it means for an institution to ‘safeguard’ this history. Du Camp’s photographs also served a colonial agenda—but by encountering this in a museum today, we have the privilege to think about this colonial lens through which they saw these findings. It calls for more open and decolonial exhibition approaches. Editor: This conversation changes the whole composition for me now! I guess in that way the original purpose and the history it went through can never really be set in stone… perhaps fittingly. Curator: I couldn’t have said it better myself. It allows the mind to truly be open about what came before us, what surrounds us now, and how we continue to move forward with a deeper understanding of the many stories that connect humanity’s journey.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.