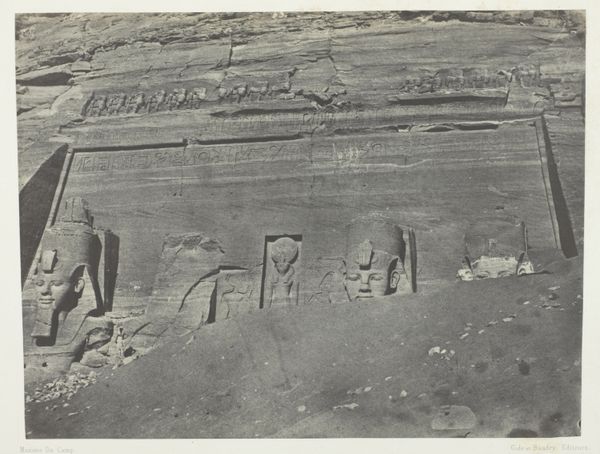

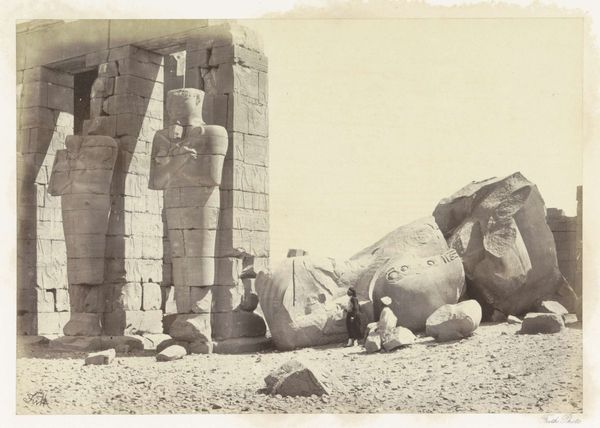

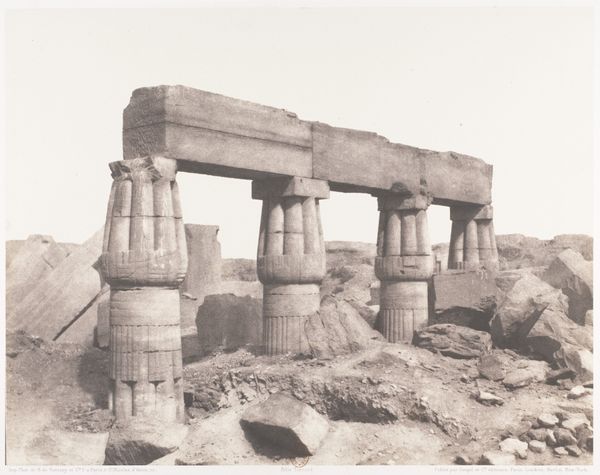

Djerf-Hocein (Tutzis), Hemi-Spéos, Colosses de la Partie Extérieure 1851 - 1852

0:00

0:00

daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

figuration

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

history-painting

#

architecture

Dimensions: 23.7 x 30.4 cm. (9 5/16 x 12 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Félix Teynard’s "Djerf-Hocein (Tutzis), Hemi-Spéos, Colosses de la Partie Extérieure," a daguerreotype from 1851-1852, captures an ancient Egyptian site with colossal figures carved into the rock face. Editor: There's something so haunting about this image, a kind of monumental stillness. The way the light catches the rough-hewn texture of the sculptures makes them feel incredibly solid, grounded in the earth, almost eternal. Curator: It's fascinating to consider Teynard's process. Imagine the technical challenges of lugging such equipment to this remote location, creating a tangible record of a place then largely inaccessible. Editor: Absolutely, and what’s so potent is the way Teynard's photograph intersects with histories of colonialism and Egyptology. These early photographs contributed to the European gaze, shaping Western perceptions of Egyptian history. We must ask: who has the power to represent these artifacts, and whose story gets told? Curator: Precisely! This photograph acts as documentation, but is also art. Look at the skill evident in this early process. The chemical treatment of the plates, the precision required to achieve this clarity… Editor: I'm drawn to the depiction of labor. The creation of the original sculptures involved massive extraction of resources and the work of countless laborers. We’re seeing a legacy of that effort but only through the selective vision of a European photographer and colonial dynamics. The perspective leaves questions about exploitation, ownership, and who gets to claim history. Curator: These are key questions. Daguerreotypes were luxury items; their production and consumption served specific elite interests. Even in its early days, photography was far from democratic. Editor: This image invites reflection on photography's complex role as both a historical record and an instrument of power and the gaze. We're implicated in that history even as we stand here looking at it now. Curator: Precisely! These works allow us to contextualize not only an ancient moment, but a more recent one as well. Editor: It's a powerful, layered piece, resonating with colonial history. Curator: Indeed, a conversation starter about perception, process, and power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.