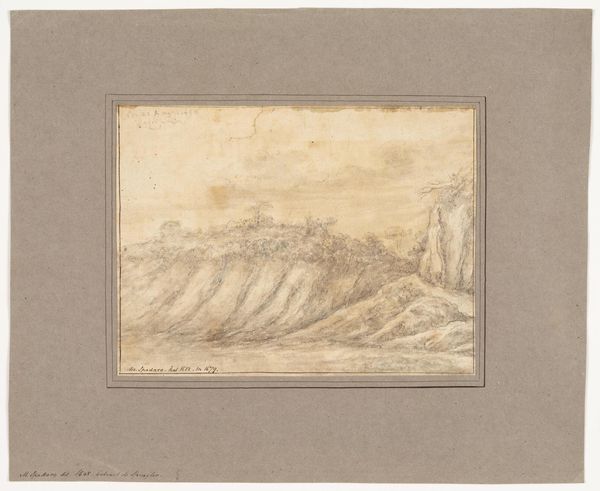

drawing, paper, dry-media, pencil, chalk, graphite

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

landscape

#

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

dry-media

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

chalk

#

line

#

graphite

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This drawing, "Tree with a Rock, beneath which sits a Shepherd" by Ferdinand Olivier, dates from 1840. It’s a beautiful landscape rendered in pencil, chalk and graphite. It feels very self-contained with its circular border and quiet mood. How do you interpret the function of an image like this, especially within its historical moment? Curator: The image speaks to a very specific desire prominent in the 19th century: a longing for an untouched natural world. Consider its role in contrast to the industrial revolution; images like these created a romanticized idea of pastoral life. Notice how the shepherd is nestled *under* the rock; this placement implies the dominance of nature over humanity. How does that strike you, thinking about how we idealize that imagery even today? Editor: I see what you mean. We still have a powerful desire for that connection to nature, often absent in our daily lives. Does the medium – the fact that it’s a drawing and not a painting – influence this reading? Curator: Absolutely. Drawings like this were often more intimate, circulated among friends and within artistic circles. They weren't intended for grand public display in the same way as paintings. This suggests a more personal and contemplative function. Who was invited to see such scenes shapes the art itself. What do you suppose the impact was in limiting the scale? Editor: That makes sense; it becomes less about national identity and more about individual feeling. I hadn’t considered how the scale dictates the image’s sociability. Thanks! Curator: Indeed! Examining the conditions of display really opens up new perspectives. This reminds us that art never exists in a vacuum.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.