![Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, 1507-1582, 3rd Duke of Alba [obverse] by Giuliano Giannini](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzL2Y2MzA3MTAzLWE2NGItNGQ5Zi04MDBhLWM3Yjc4NzFjOGZhNC9mNjMwNzEwMy1hNjRiLTRkOWYtODAwYS1jN2I3ODcxYzhmYTRfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

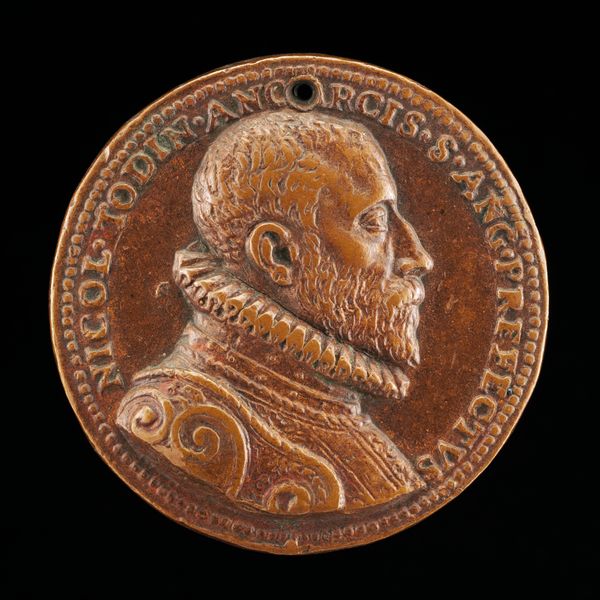

Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, 1507-1582, 3rd Duke of Alba [obverse] c. 1580

0:00

0:00

metal, bronze, sculpture

#

portrait

#

medal

#

metal

#

stone

#

sculpture

#

bronze

#

mannerism

#

sculpture

#

history-painting

Dimensions: overall (diameter): 3.68 cm (1 7/16 in.) gross weight: 15.01 gr (0.033 lb.) axis: 5:00

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: Here we have a bronze medal, dating from around 1580, depicting Fernando Alvarez de Toledo, the 3rd Duke of Alba. It presents a stern profile of the Duke. What's your initial reaction to this piece? Editor: My first thought is the remarkable detail captured in such a small format. It's impressive how the artist conveys not just likeness, but also a sense of the Duke's character and status. There’s something about the cool, almost aloof expression. Curator: Indeed. Consider the process; crafting something like this demanded a specific expertise in metallurgy, mold-making, and chasing. The very act of creating it elevated the subject—bronze, historically associated with commemorative works and durable artifacts, solidifies Alba's status. Editor: And looking at Alba's historical role adds another layer. He was a controversial figure, known for his firm hand in the Netherlands. This medal, therefore, serves not just as a portrait, but as a statement of power, crafted for political messaging. Where might something like this have been displayed? Curator: Likely in aristocratic circles, or perhaps commissioned as a gift within the network of powerful Spanish nobles. We should also think about the skilled labor necessary; specialists in workshops produced these medals, indicating a whole system of artistic production and patronage that supported works like this. Editor: Absolutely. The choice of bronze is crucial. A cheaper metal would convey less importance, but bronze suggests permanence. It's almost like they're trying to cast Alba in history, so to speak, not just portray him. This helps construct a lasting legacy through imagery and object. The medal subtly influences viewers. Curator: Precisely. And the detail – the elaborate ruff, the expertly crafted beard – all of this signifies wealth, power, and refined taste. This work is a small piece, yes, but monumental in what it tells us about materiality and meaning during the period. Editor: It gives you pause to think how objects shape perspectives and what histories are pushed into public view, or intentionally obscured. Curator: Indeed, it leaves us with plenty to reflect on about the strategies of image making, patronage and dissemination of portraits in the 16th century. Editor: I agree. This really prompts us to remember that objects are never silent; they participate in historical conversations, and continue doing so for us now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.