drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

#

erotic-art

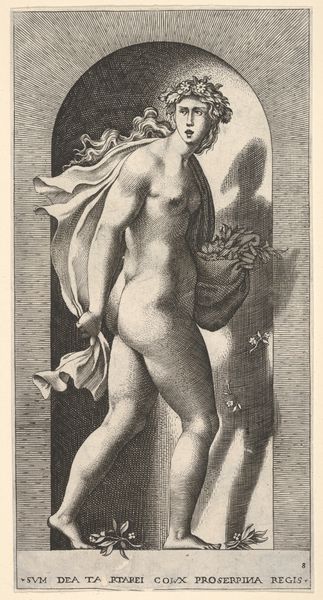

Dimensions: sheet: 7 3/8 x 3 9/16 in. (18.8 x 9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

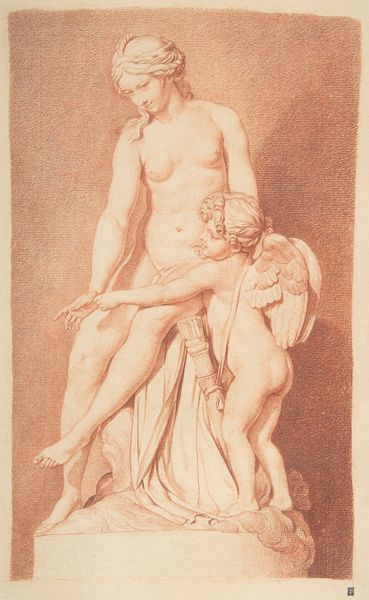

Editor: Here we have "Venus and Cupid," a print by René Boyvin, sometime between 1525 and 1600. There's an almost unsettling vulnerability to the figures... How do you interpret this work, particularly within its historical context? Curator: That vulnerability you observe is a key point of entry. Renaissance depictions of Venus are rarely just celebrations of beauty. We have to consider the politics of representation here. Who is Venus for? For whom is this female nude being presented? Think about the male gaze, the power structures inherent in depicting a female figure—even a goddess—in this way. Is it truly celebratory, or is it objectification masked as art? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn’t really thought about the power dynamics in the portrayal of Venus herself. Does Cupid change that at all? Curator: He complicates it, certainly. Cupid, often interpreted as a symbol of desire or affection, can also signify the imposition of patriarchal expectations on relationships. His presence underscores a potential reading of the print not as an innocent depiction of love, but as an allegory of the constraints placed upon women. Does Venus have a choice here, or is she, too, bound by Cupid’s arrow, by societal expectations? Editor: So you're saying even depictions of mythology are embedded with political undertones of the time. How do we apply this lens when viewing other art pieces of the period? Curator: It’s about questioning the surface. Consider who commissioned the work, who was the intended audience, and what social narratives were prevalent at the time. Ask yourself: whose voices are amplified, and whose are silenced? Through that critical engagement, we begin to unravel the complex interplay of art, power, and identity. Editor: I guess that's true; it gives us more nuance, a broader understanding of not only the art but ourselves in relation to it. Curator: Exactly. And remember, engaging with these historical perspectives isn't about condemning the art of the past, but about fostering a more critical and inclusive dialogue with it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.