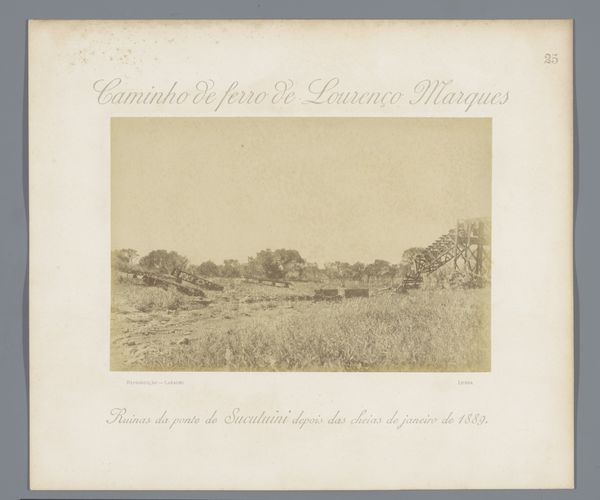

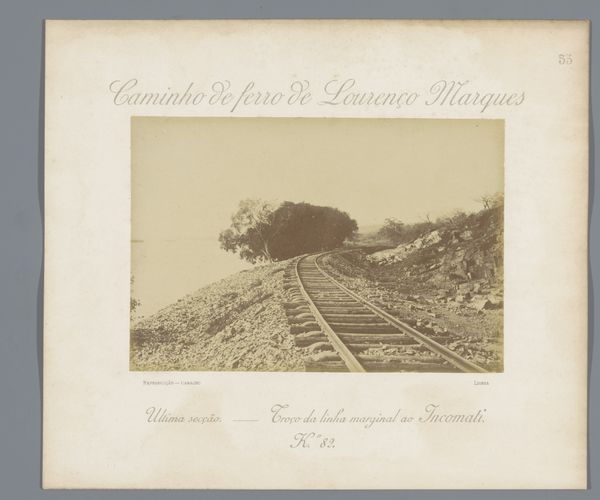

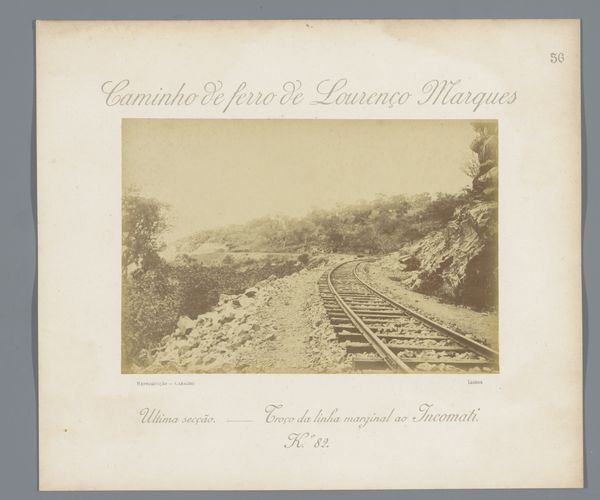

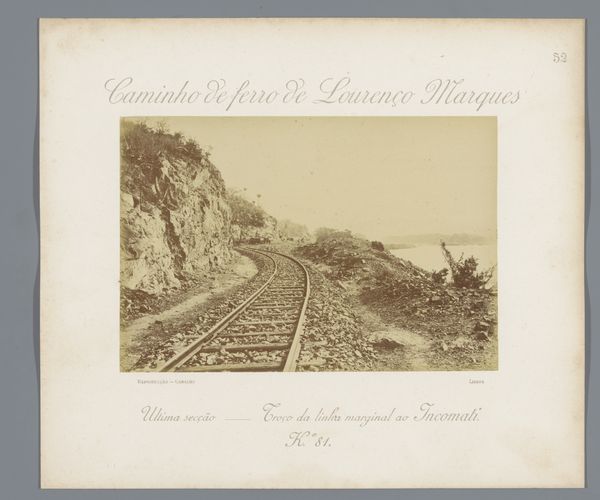

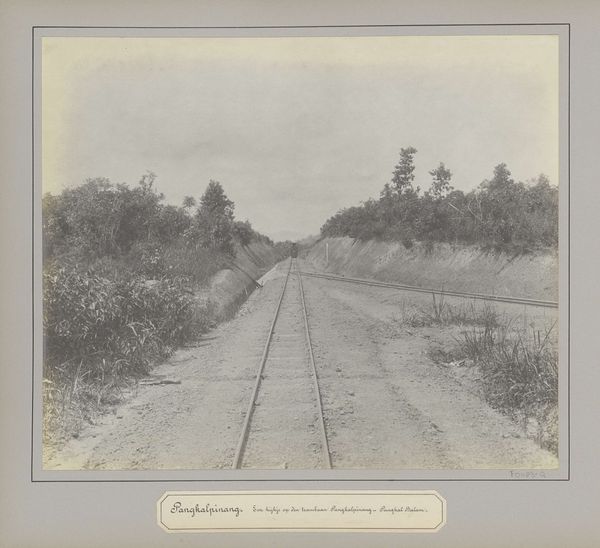

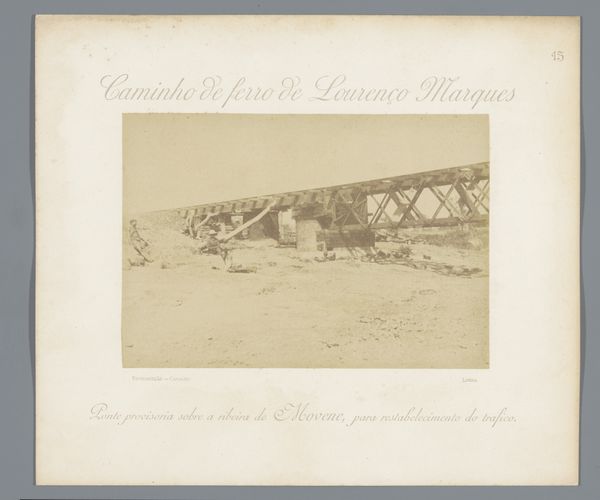

Treinspoor in de buurt van de brug over de Rio Movene in Mozambique c. 1889 - 1895

0:00

0:00

photography

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

realism

Dimensions: height 110 mm, width 166 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Well, this feels like a portal into another time. I am struck by the wistful emptiness, almost haunted—those stark, skeletal trees framing the scene add such an ominous tone. Editor: Yes, the desaturated tones definitely contribute to the somber mood, but when you delve into its historical context, this photograph becomes more than just an atmospheric landscape. It's titled “Treinspoor in de buurt van de brug over de Rio Movene in Mozambique,” which roughly translates to "Train track near the bridge over the Movene River in Mozambique.” Curator: I'm so intrigued, but what about it grabs you, really? Editor: This image, taken around 1889-1895 by Manuel Romão Pereira, situates itself within a really difficult legacy of colonial infrastructure. We are not simply viewing a landscape; instead, we are presented with an instrument of occupation and resource extraction during the Portuguese colonial era. Curator: Hmmm. I notice how the tracks cut through the land, straight into the distance. This is no tender exploration—I feel its blunt intrusion, that very directed purpose! And that horizon line vanishing to points unknown...gives me goosebumps! Editor: Precisely. While technically showcasing realist photography, images like these conveniently gloss over the immense human costs associated with projects like the Lourenço Marques railway. They actively omit or downplay the experiences of indigenous workers. Curator: I suppose viewing a photograph, so seemingly neutral and detached on the surface, you have to constantly question whose reality is actually reflected? What exactly does it choose to show...and hide? Editor: Exactly, what does get centered in the picture and, as you noted, what disappears out of frame, that’s so crucial here. Viewing photographs critically also includes understanding the social and political contexts in which it came to be. We must ask ourselves who gets to tell the story and from whose perspective, especially given its position during the era of high colonialism. Curator: I get it. It's definitely powerful—both visually and symbolically—this dialogue that exists, once you look closely at it and remember all its unspoken parts. Editor: I completely agree. By acknowledging both the aesthetic qualities and historical contexts, we engage more mindfully with our colonial past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.