Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

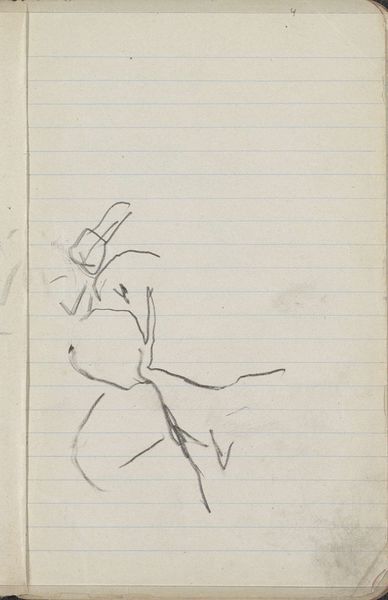

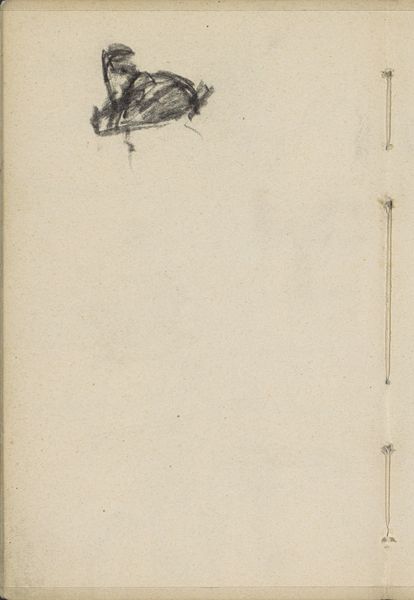

Curator: At first glance, it looks like a child’s hasty doodle on notebook paper. Editor: I agree, but sometimes those quick sketches reveal more than polished portraits. Let's delve deeper. We're looking at "Ruiter," a drawing by Isaac Israels, likely created sometime between 1875 and 1934. It’s rendered in pencil on paper and currently resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Curator: Israels often captured fleeting moments from everyday life. His subjects tend to explore class, labor and often subvert social norms with a subversive sense of humor. Here though, the sketch evokes an almost naive sense of motion; an attempt to capture the rider’s essence more than its detailed appearance, which for me opens questions of masculinity. Editor: It's a great example of the Impressionist spirit; that striving to capture an instantaneous impression. Its looseness, bordering on abstraction, contrasts sharply with earlier academic art. It really draws attention to the skill of reducing form to bare essentials, while still communicating action. The horse seems captured mid-leap. The social aspect interests me – the accessibility of riding, who has that leisure and what did it signify for those participating in it and watching? Curator: Precisely. The "bare essentials" is also fascinating in this work when considered with the history of art theory where drawing was typically seen as the genesis, the under-painting for other “more serious” and accepted art like painting. So, to display something like this brings up many thoughts on intention, authorship, hierarchy, etc. I think these quick impressionistic drawings humanized those in positions of power who previously only could be immortalized in heroic life-size statues or grand history paintings. Editor: This sketch offers us a keyhole view into the world, at leisure and perhaps also into the artist’s process of image creation and dissemination through its later translation in painting form. Thank you for these thoughts, fascinating. Curator: Likewise, a reminder that even seemingly minor works can open rich dialogues about art history, representation, and power structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.