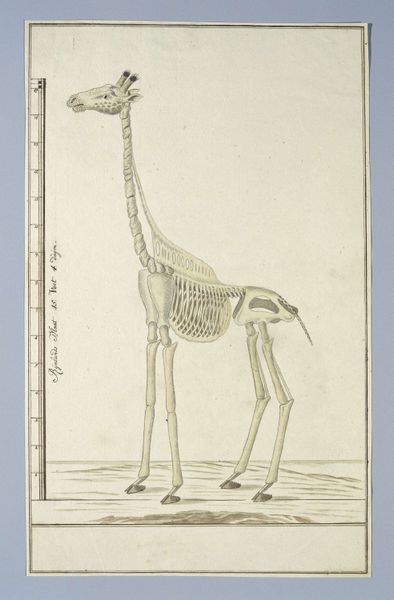

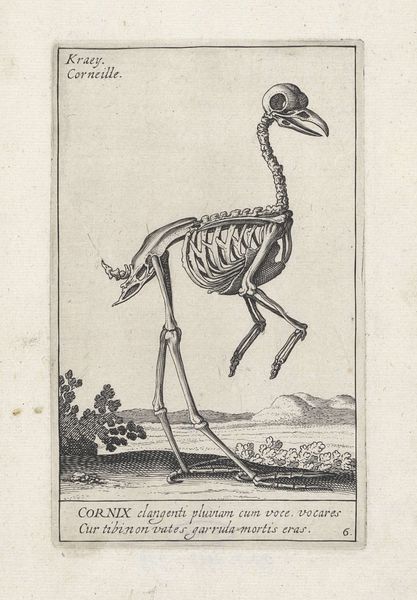

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

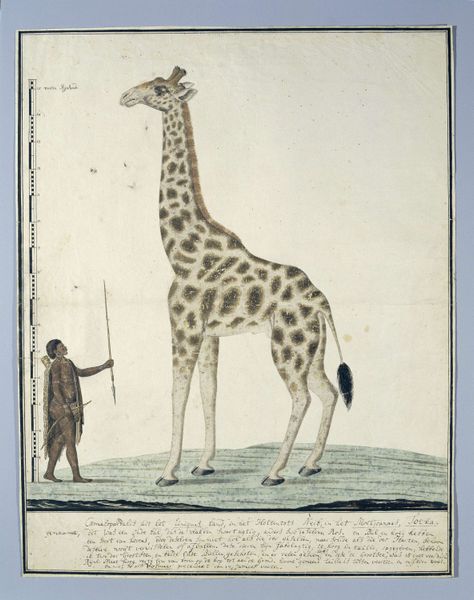

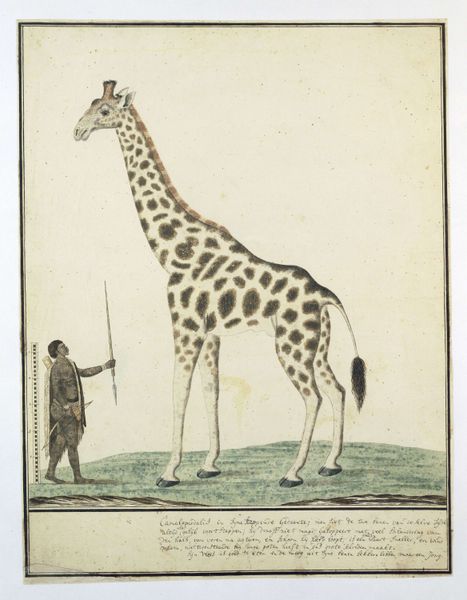

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 410 mm, width 264 mm, height 375 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

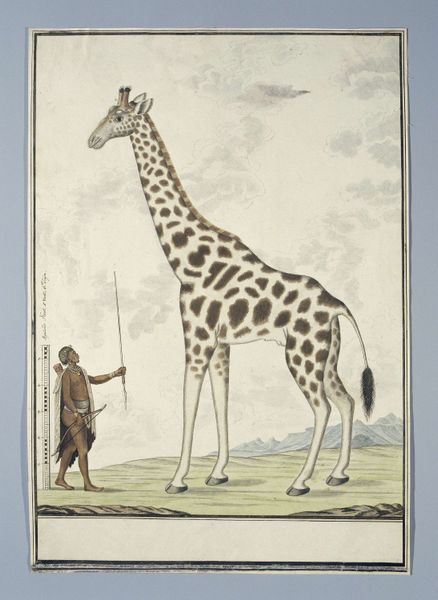

Editor: So, we're looking at Robert Jacob Gordon's print, likely from 1779, called "Giraffa camelopardalis (Giraffe), skeleton." It's an engraving, a landscape of a giraffe skeleton! The rendering feels very clinical and academic. How would you interpret this piece, given its historical context? Curator: Well, viewing this from a historical lens, we must remember that the late 18th century was a period deeply shaped by the Enlightenment. The insatiable appetite for classifying and understanding the natural world fueled scientific expeditions and a surge in natural history collections. How do you think images like these were utilized in that socio-political climate? Editor: Probably for study? The image has a ruler to the left which clearly wants to indicate measure or proportion. Maybe to classify the animal against other known species? Curator: Exactly! And it wasn’t just about detached scientific inquiry. Consider the politics embedded in it. European powers were expanding their colonial reach, encountering new flora and fauna. Images like this circulated back home, fueling narratives of control, knowledge, and possession. This isn’t just a giraffe skeleton; it's a symbol of a world being mapped, claimed, and displayed for European audiences. Note how he signs the work. What does this reveal? Editor: It's a signifier that the artist encountered this for the Prince of Orange, and sent to his Cabinet? That it was okay to possess and document? That it reflected a patron's cabinet of curiosity or art, both in collecting of worldly knowledge and acting as symbols of prestige and political clout? Curator: Precisely. And where does this position the giraffe itself, within this cultural exchange? What I mean is - who benefitted most? Editor: True. It makes you wonder what the long-term implications were of creating and disseminating such works of art. The representation almost seems more important than the animal itself, becoming less an animal and more an...emblem. Curator: An emblem not of nature, but of empire. It reminds us to question what power dynamics might be at play within scientific study. Editor: That gives me a lot to think about. It highlights the subtle ways art, even what looks like a simple illustration, participates in broader cultural and political narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.