photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

black and white photography

#

landscape

#

street-photography

#

photography

#

black and white

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

monochrome photography

#

realism

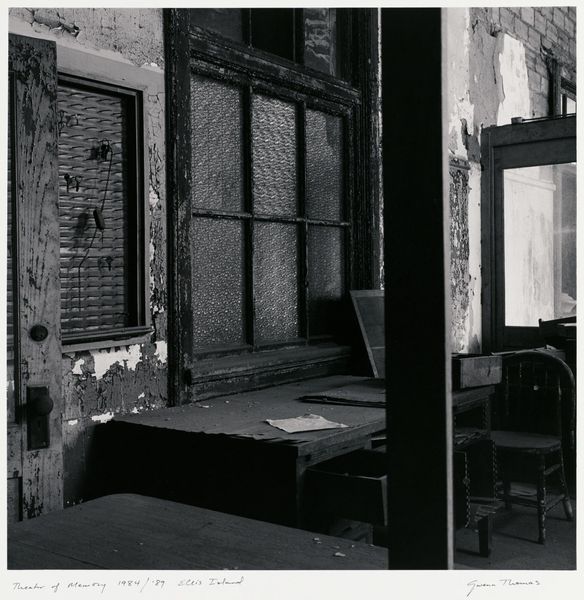

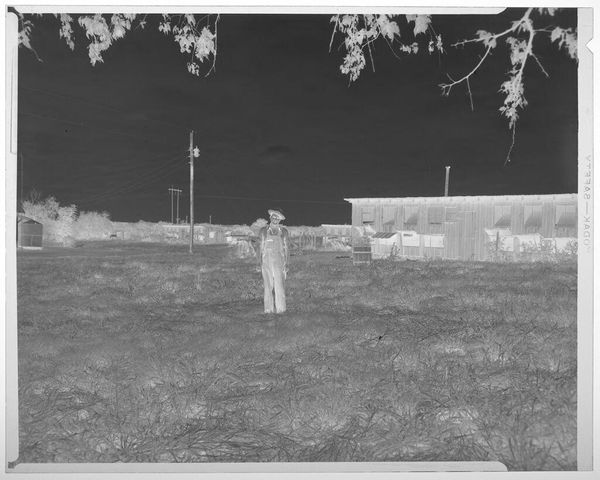

Dimensions: overall: 20.2 x 25.2 cm (7 15/16 x 9 15/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

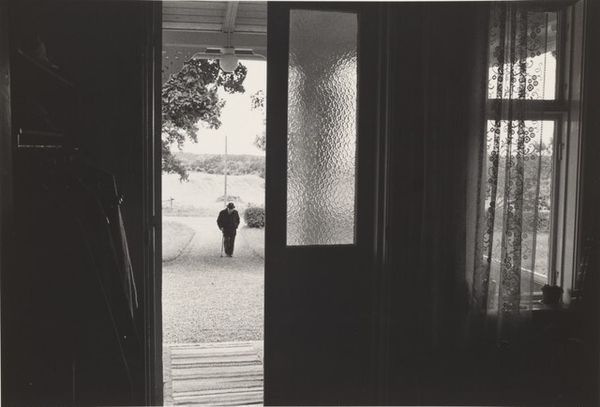

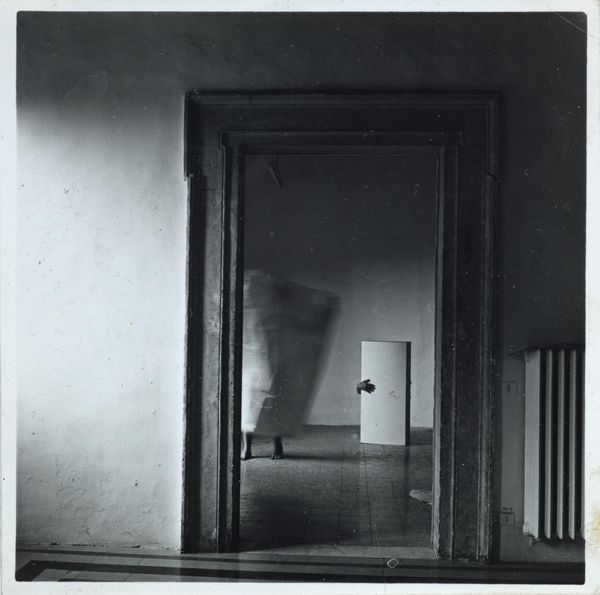

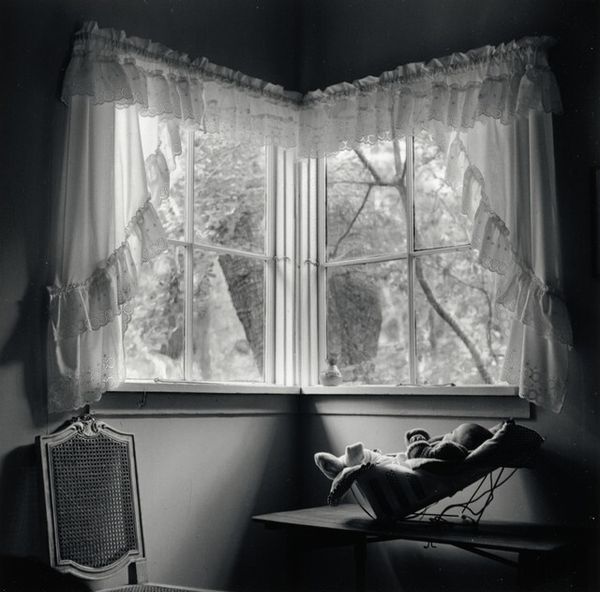

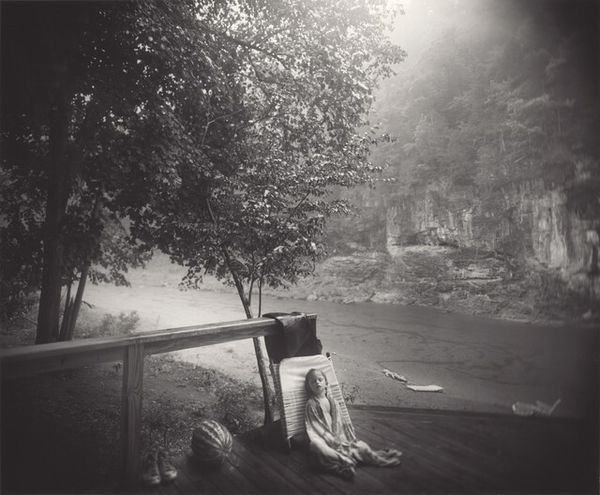

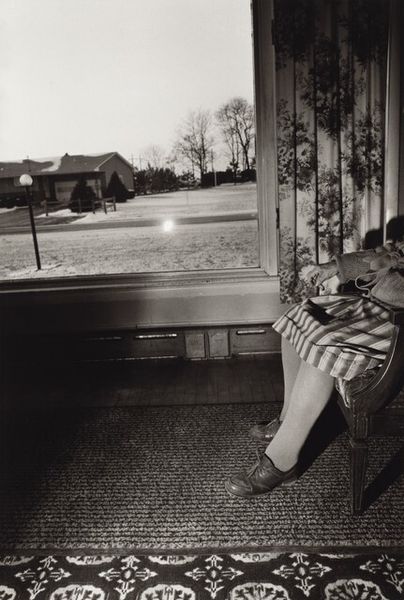

Curator: Emmet Gowin’s gelatin silver print, “Edith, Danville, Virginia” from 1971, presents a quietly powerful portrait. What are your initial thoughts on this image? Editor: Stark. I immediately notice the contrast, the darkness encroaching on the edges, making it feel enclosed, almost claustrophobic, despite being an outdoor scene. It feels like a visual representation of vulnerability and resilience coexisting. Curator: The photographic process itself plays a part. Gowin’s use of a wide-angle lens creates that distortion, pulling the periphery into darkness, yes. Edith, who is Gowin’s wife, becomes the central icon here, framed by the doorway as she stands in the background. We see how his intimate relationship impacts his perspective, drawing visual metaphors for connection, separation and the photographic gaze. Editor: Absolutely, this isn’t just a portrait; it’s a social document too. There’s a clear visual hierarchy – the outside and inside realms, where the darker natural spaces compete for importance with the artificially-constructed human-created home. Edith’s place in the domestic is central but she peers at us. She looks back. Curator: The light is carefully modulated and directed: Notice how her figure glows in the doorway compared to the receding perspective behind the door into the sun-drenched outdoors? It is an unusual and complex compositional technique to show simultaneous distance, framing, connection and light. Editor: I wonder how conscious we are, in today’s art world, to consider the context of the artist, and his vision of a patriarchal lens versus what is was to exist, as Edith did, as a woman in a rural part of the USA at this moment in time. How does the history of representations inform our views on this art? Curator: Your point raises complex issues. The work presents Gowin's perception, filtered, considered, with its particular historical positioning and framework, but that does not mean there are no visual resonances of that positioning that inform this powerful image. And she stands. She watches. She gazes back. It remains as a memory. Editor: True. Art does not exist in a vacuum; the artist's subjectivity inevitably shapes what they create. It prompts me to think about all the unrecorded narratives. But these complex silences are as vital a testament, aren't they? The act of choosing—of seeing—is inherently political. Curator: Precisely. Thinking about it this way makes me look again, reconsider and remember that nothing exists alone, but within systems of connection and memory. Editor: Likewise. What resonates most now is its enduring visual tension, reminding us of the complexities in portraiture and how they are always anchored within place, people and time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.