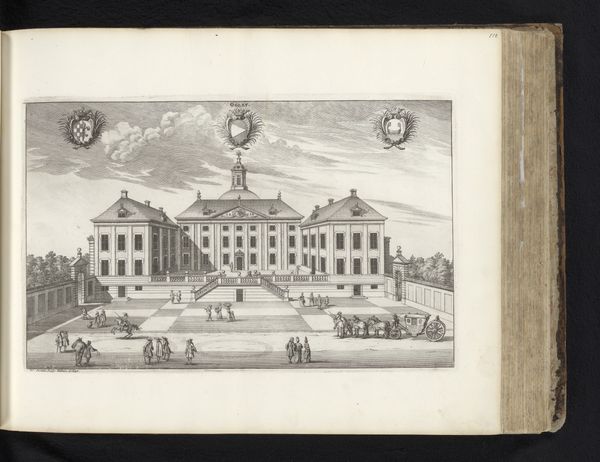

Gezicht op het binnenplein van de buitenplaats Zijdebalen aan de Vecht bij Utrecht 1719

0:00

0:00

danielstopendaal

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 163 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

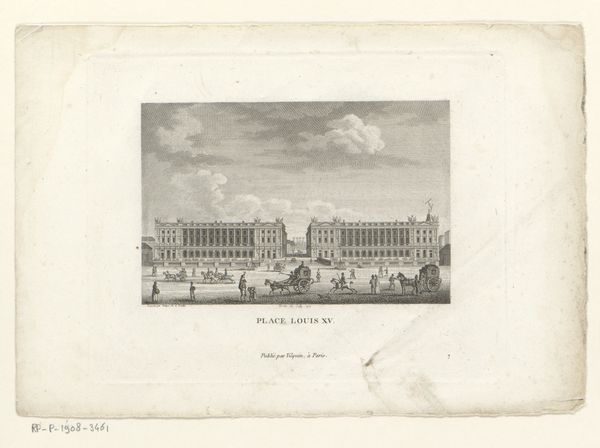

Curator: This engraving by Daniël Stopendaal, created around 1719, offers us a detailed glimpse into the Zijdebalen estate along the Vecht River near Utrecht. Editor: Immediately, the ordered layout catches my eye. There’s a rigid formality to it all; from the symmetrical architecture to the pruned trees lining the courtyard. Curator: Indeed. Stopendaal's meticulous depiction serves as both art and a social document, reflecting the tastes and aspirations of the Dutch elite during the Baroque era. The print likely functioned as a promotional piece, a testament to the estate's grandeur and its owner's social standing. Editor: The medium itself, engraving, underscores that point. The meticulous and precise technique of engraving—cutting into a metal plate, inking, and printing—echoes the controlled environment it depicts. And look at the arrangement of figures along the perimeter – their labor, of course, maintaining this facade. Curator: Absolutely. Notice, though, the way the architecture dominates. It dwarfs the people enjoying or tending to the grounds. This suggests a social hierarchy inherent within the image itself, emphasizing power through scale and composition. Editor: Right, the building becomes almost a stage, or a backdrop. Think about the human effort involved, though. From quarrying the stone to laying out the formal gardens – that much material extracted, formed, and arranged to uphold these social constructs. Curator: Certainly, the construction and upkeep represented significant investment and control over resources. What I find particularly interesting is how prints like this circulated. They made these exclusive spaces visible to a broader public, shaping perceptions and even fueling aspirations across different social strata. Editor: I’m struck, thinking of the artist's labor in realizing this at scale. It isn't simply about rendering a pleasing likeness. The time it takes to translate these stones, figures, and reflections in black and white– an effort invisible in this final rendering. Curator: Viewing Stopendaal’s engraving today, we can consider how it reflects the broader cultural and economic systems of the 18th century and how art both mirrors and reinforces social norms. Editor: Exactly. Reflecting on its material qualities allows us to unravel layers of social investment and human impact beyond its aesthetic value.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.