Dimensions: height 175 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

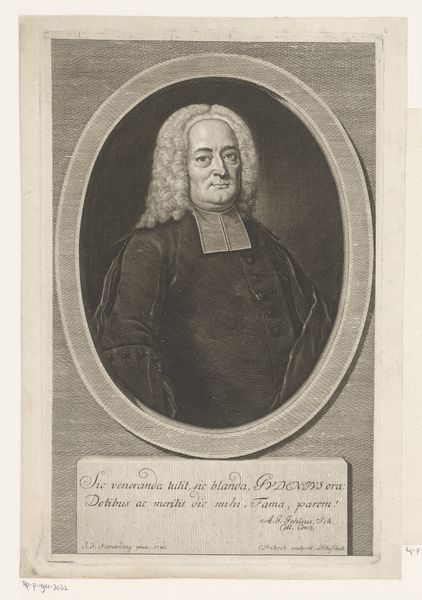

Curator: Here we see "Portret van Wilhelm Abraham Teller," crafted sometime between 1768 and 1817 by Johann Heinrich Lips. It's an engraving, a meticulously worked print. Editor: My first thought is how… buttoned-up it feels. Everything is contained: the tight frame, the symmetrical composition, the subject’s rather austere expression. What can you tell us about him? Curator: Wilhelm Abraham Teller was a prominent German Protestant theologian and advocate for theological rationalism. This portrait, like many of the era, seeks to convey authority and intellect through carefully constructed symbolism. Editor: Symbolism achieved through material manipulation. Think about the labor involved in engraving, the skill in rendering tonal variation through tiny, precise lines. And then the material: the ink, the paper, the press itself, all reflecting a society deeply invested in dissemination of knowledge – albeit among a certain class. Curator: Exactly. The wig, for example, wasn’t just a fashion statement; it signified status and belonging to an educated elite. And the dark coat contrasts with the white clerical collar, further emphasizing his religious office. We are meant to see him as a man of reason and piety, intertwined. Editor: I see the societal function of prints like this, almost like shareable profile pictures designed to construct and reinforce power structures. Someone dedicated hours etching away at a metal plate. Consider how this multiplies and ends up framed in other households or tacked to walls. The portrait normalizes his place and position. Curator: The eyes draw you in, don't they? There's a weight of expectation there. The gaze seeks to meet yours across centuries. This is the cultural memory that is trying to take hold, that very particular moment that says remember, remember, remember this kind of thinking, remember this importance of status. Editor: Yes, though I also can’t help but wonder about the economic realities of printmaking at that time. Who was consuming these images, and how did the economics influence not just production but also reception? The paper itself—was it locally sourced or imported? Were the inks created locally and how did the cost contribute to the ultimate "pricelessness" of the piece? Curator: I hadn’t considered that but you’re right to remember those aspects of history. Thanks for highlighting that intersectionality, that those factors shape even seemingly immutable icons like this one. Editor: Precisely. And thinking about the hands that produced this print forces us to reconsider what we give significance to and how we define value. Curator: I'm grateful for a deeper awareness and will certainly reconsider and incorporate that into future viewings of this portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.