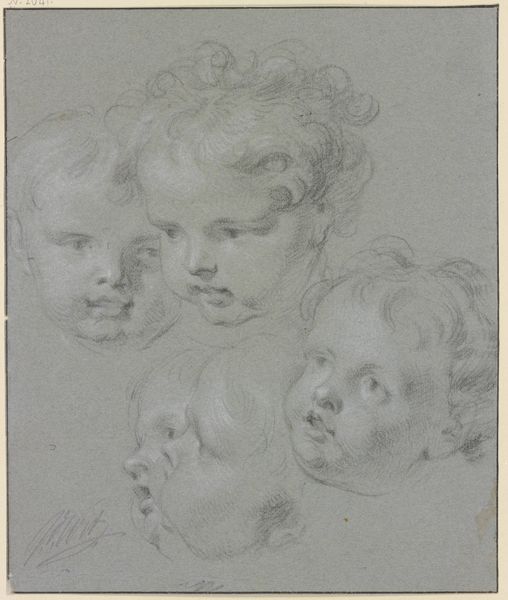

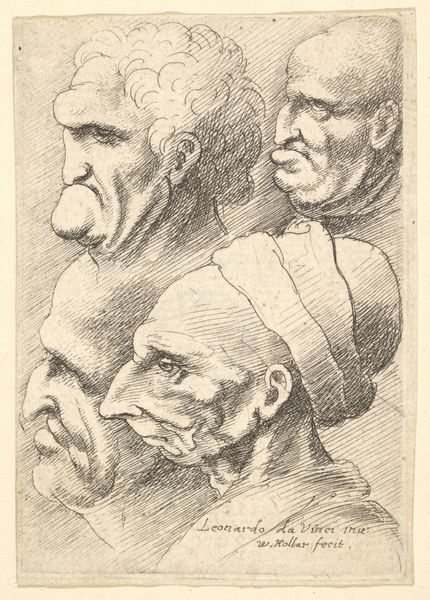

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

portrait reference

#

child

#

group-portraits

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 2 1/4 × 3 5/8 in. (5.7 × 9.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Let’s delve into Wenceslaus Hollar’s “Three Children’s Heads,” created in 1645 and held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. An exquisite Baroque engraving! What strikes you most about it initially? Editor: The precision of the line work is captivating! Look at how much texture and depth he achieves with just engraving, from the tight curls to the subtle modeling of the faces. Curator: Absolutely. The image offers insight into seventeenth-century portraiture norms and childhood, wouldn't you agree? The way Hollar portrays these children connects to the prevalent social perspectives on youth at that period, frequently representing innocence, fragility, and the aspirations imposed on children through their depiction in the group portraiture format. Editor: It certainly does make one wonder about their individual identities and perhaps even the role of child labor at the time! Engraving, being a laborious and detailed craft, probably made these accessible to wider audiences than paintings; imagine the social function of multiplied images, how families might use these likenesses for remembrance. Curator: That’s a compelling material reading. Consider also the power dynamics in play – were these children from a privileged class, given the commission? Or perhaps a demonstration of Hollar’s skill, allowing for patronage? I wonder how Hollar navigated representing children when childhood as we understand it today was still forming. The uniformity across the subjects—note the hairstyle, features—might imply class, reinforcing existing societal hierarchies. Editor: The way the burin moved across the copper plate speaks volumes. What were the conditions of Hollar's labor? Were assistants involved? These material aspects give weight to the social implications of creating reproducible images, shaping visual culture of the time. I wonder about the distribution networks. Curator: It is worth investigating further into the production process of such engravings during the Baroque period. Understanding his access to materials and workshops adds important nuance, doesn’t it? But overall, I can't help but see in this portrait how concepts of childhood were constructed and how artistic conventions reinforced them, influencing perceptions of innocence and potential. Editor: Definitely. The physicality of printmaking underscores the circulation of imagery. The medium profoundly affected its reception and enduring relevance. I am still so moved by Hollar’s use of materials!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.