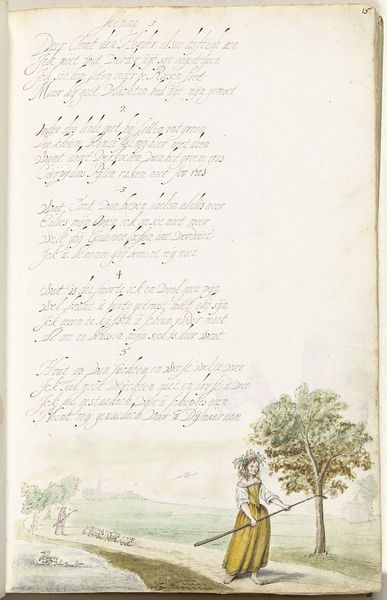

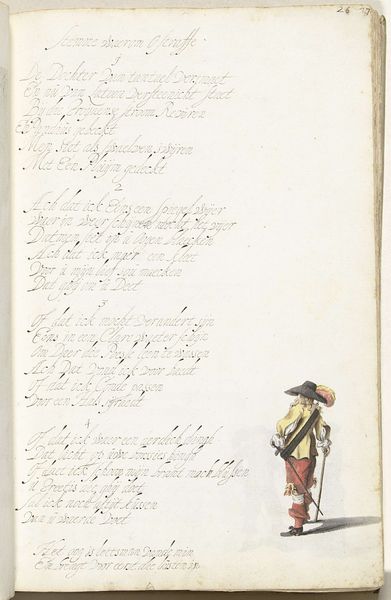

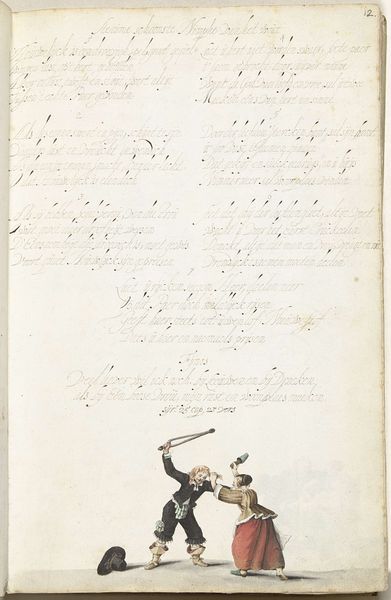

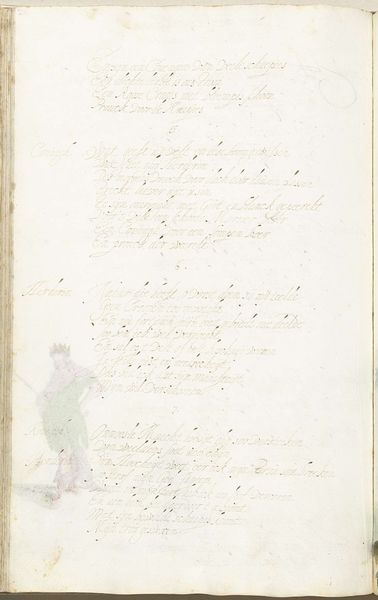

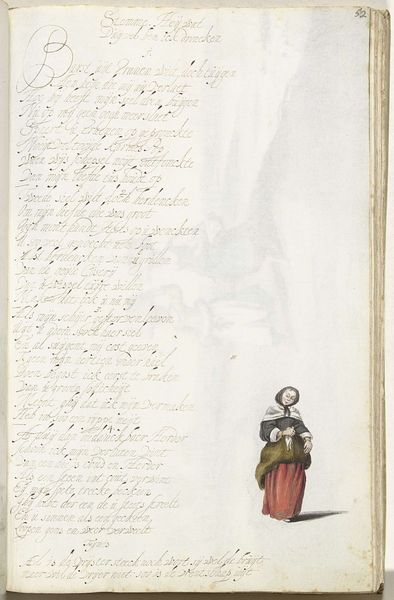

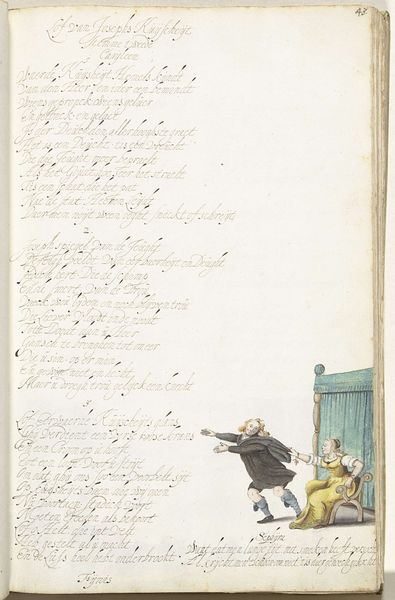

drawing, paper, watercolor

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

#

paper

#

watercolor

#

miniature

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 313 mm, width 204 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me immediately is the stark emotional intensity. A tiny coffin at the bottom of the page and above it lines of almost illegible handwriting. It's an incredibly moving little image. Editor: We are looking at a piece entitled "Vrouw met het stoffelijk overschot van haar geliefde," or "Woman with the Corpse of her Beloved," created around 1653 by Gesina ter Borch. It’s currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Ter Borch was a Dutch Golden Age artist known for her exquisite drawings, often incorporating watercolor. Here, she used watercolor and ink on paper to craft what appears to be a miniature, almost like an illuminated manuscript page. Curator: Manuscript, yes! It reminds me of the "Ars Moriendi," or the Art of Dying tradition – those illustrated manuals for preparing oneself and one’s family for death. This image carries that same weight, but it is incredibly personal and immediate, almost diaristic, despite the artistic conventions that it borrows. The way she captures the woman's grief – turned away, head bowed, clutching what looks like a wreath, while the body of the deceased lies in the coffin – speaks volumes about the personal experience of loss. Editor: Indeed, Gesina ter Borch created this at a fascinating period in Dutch history, a time marked by both immense prosperity and also recurring outbreaks of plague and other diseases. This type of grief would've been ever present. What’s especially striking about this work is that it appears in what art historians believe was a family album, likely containing various images, writings, and keepsakes celebrating important life moments for the Ter Borch family. So the act of remembering and the politics of remembrance is something she likely took very seriously. It brings up fascinating questions of class and access. It also invites the viewer to meditate on issues of gender roles in the 17th century. Curator: I see how you’re framing the historical significance, how that affects our reading of it today. Yet, there is a universality here, no? This wasn't commissioned, this wasn't supposed to play a particular part in the art world. That authenticity really does come through in the lines, the gestures. And what could feel more relevant than a study of how to live, how to grieve? Editor: Precisely. Perhaps what we find enduring about it is its simple, affecting depiction of a universal human experience, framed through the specifics of its time and place. Curator: Thank you, yes, that tension is exactly why it strikes a chord even now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.