Twee figuren in een aangemeerde roeiboot aan een waterkant c. 1825 - 1829

0:00

0:00

andreasschelfhout

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

pencil work

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

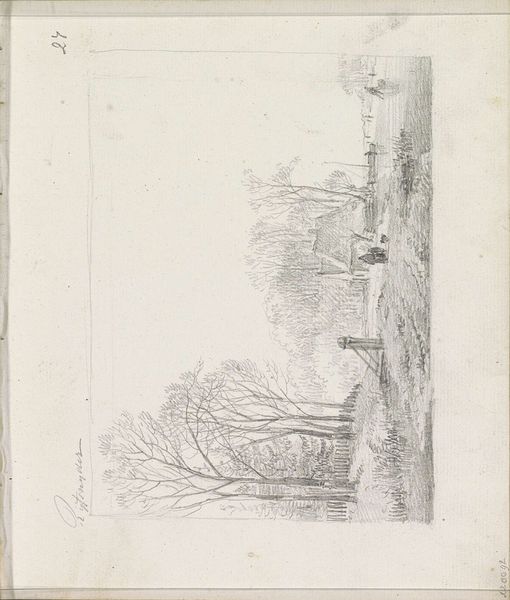

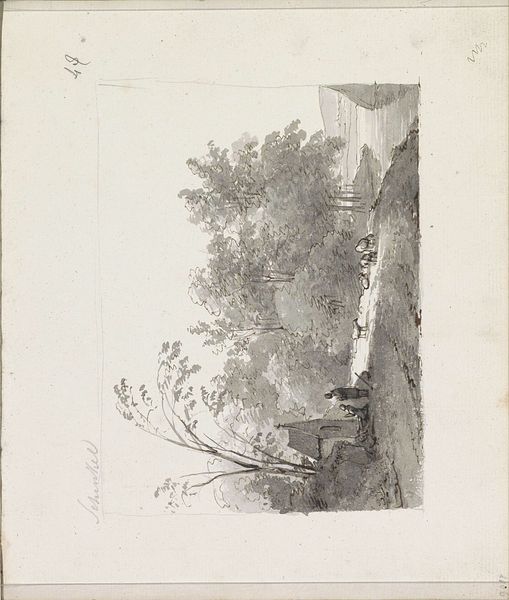

Editor: Here we have "Two Figures in a Rowboat Moored at the Bank," a pencil drawing by Andreas Schelfhout, dating back to the late 1820s. It's a very subtle work, almost ghostly in its rendering. What strikes you about it? Curator: The very *process* of this piece reveals much. Look at the marks, the visible labour of creation. What was Schelfhout intending by choosing such a simple tool, the humble pencil, for this landscape? Was this a study, a sketch done on site to prepare for a more "finished" work? Editor: Possibly, yes. It does feel preliminary. What does that tell us? Curator: It disrupts the traditional hierarchy, doesn’t it? A “finished” oil painting, presented as high art, versus the simple pencil sketch, traditionally viewed as a preparatory step. This drawing highlights the material reality, the labor, that *underlies* the creation of idealized landscapes of the Dutch Golden Age and Romanticism. It questions what is valued, doesn't it? Is it the pristine final product, or the evidence of the artist's hand and thought process? Editor: I see what you mean. The focus shifts from the romantic subject matter to the very means of its representation. The pencil work, the social context of creating such drawings becomes prominent. Curator: Exactly. The very limitations of the pencil, its monochrome nature, challenge the lush, colorful visions often associated with landscape paintings of the time. What can we tell about class structures, commerce or other forces at play in this era? Where would you go next to dig a little deeper here? Editor: This gives me a whole new way of approaching landscape art; thinking about production rather than just aesthetic beauty is truly eye opening! Thanks! Curator: My pleasure, thinking about the economics of pencil production itself could fill volumes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.