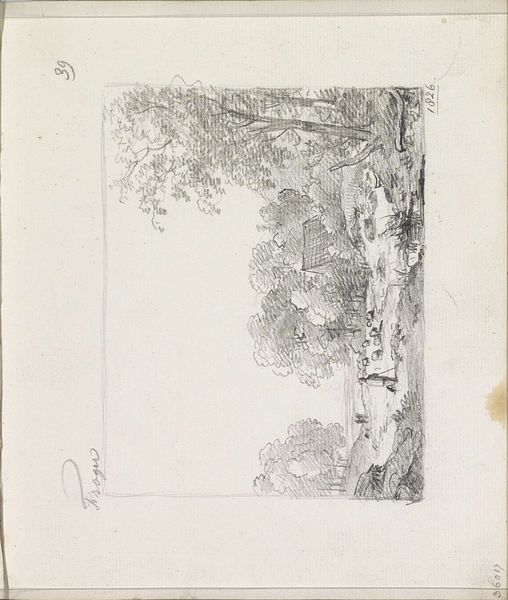

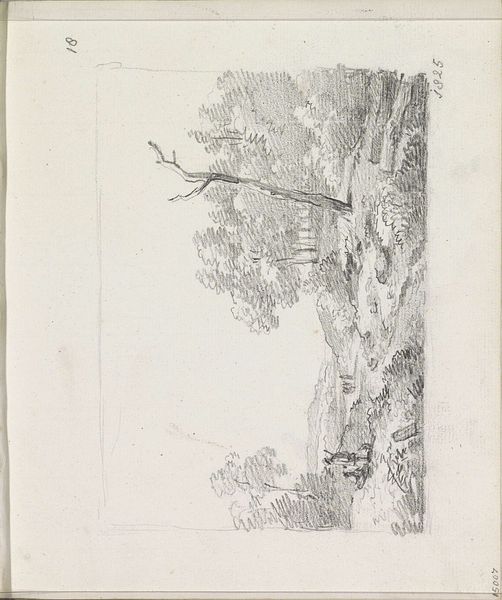

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

etching

#

paper

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

romanticism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

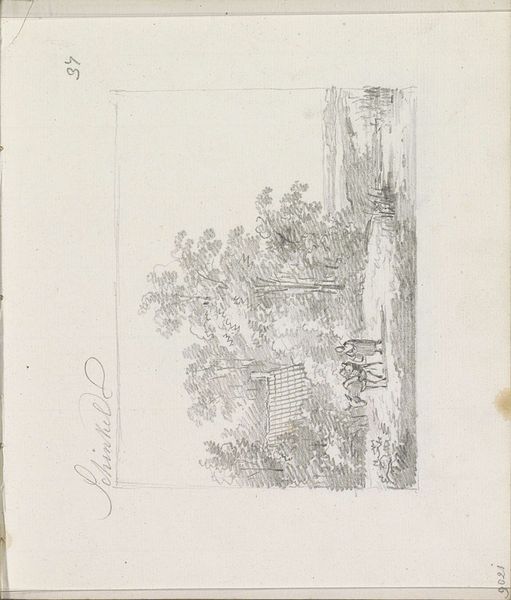

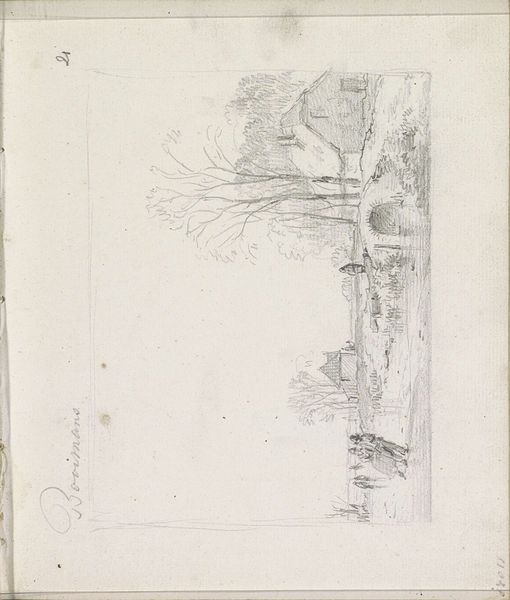

Editor: Andreas Schelfhout's "Landscape with a House, Cows and Figures," an ink drawing on paper from the late 1820s, presents a pastoral scene. What strikes me is how delicate and fleeting it feels, like a memory sketched quickly. What do you see in this piece, considering its historical moment? Curator: Well, it’s interesting you use the word “fleeting.” That speaks to Romanticism’s interest in capturing fleeting moments and personal experiences. But this is also an artist who understood the market. Landscape was increasingly popular, reflecting a growing urban population’s idealization of rural life. Editor: So, the idealization shaped its reception? Curator: Precisely! The rise of landscape paintings coincided with significant social changes – industrialization, urbanization. People yearned for a simpler, perhaps imagined past, which this drawing provides. Notice how Schelfhout composes the scene? The house, cows, and figures aren't merely objects but elements that evoke a specific mood and connection with nature. Consider who bought these drawings, and what this image offered them. What stories could they project onto it? Editor: It makes you think about who could afford art like this, and what messages they wanted to see reflected back. The drawing itself is so accessible in its subject matter but less so to the wider public, I imagine. Curator: Exactly! And think about how the museum shapes its meaning today by framing and presenting it. We're participating in this ongoing conversation about its value and relevance. Editor: That's a great point. It reframes the piece, not just as a beautiful scene but as a historical object shaped by so many different hands, literally and figuratively. Thanks for that deeper insight. Curator: My pleasure. It's a reminder that every artwork has a history that extends far beyond the canvas, intertwining with social and political narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.