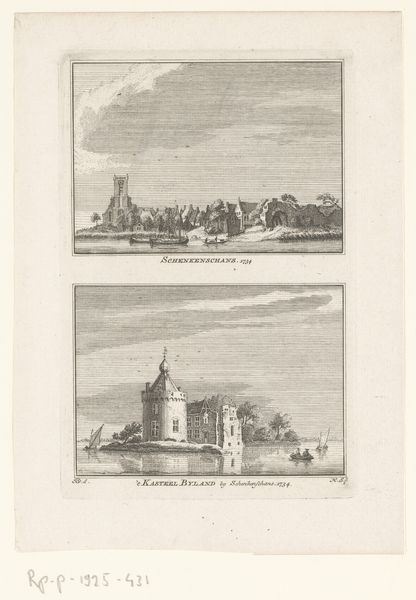

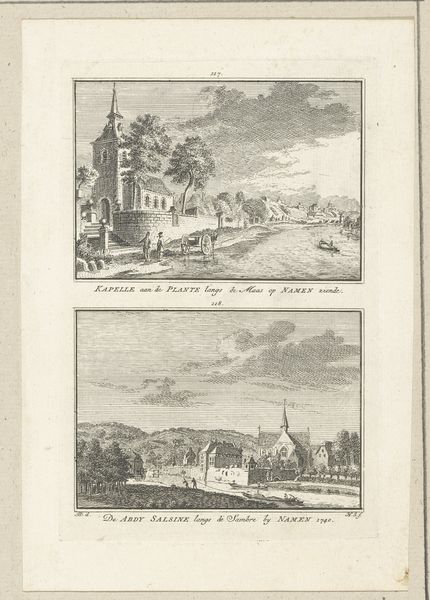

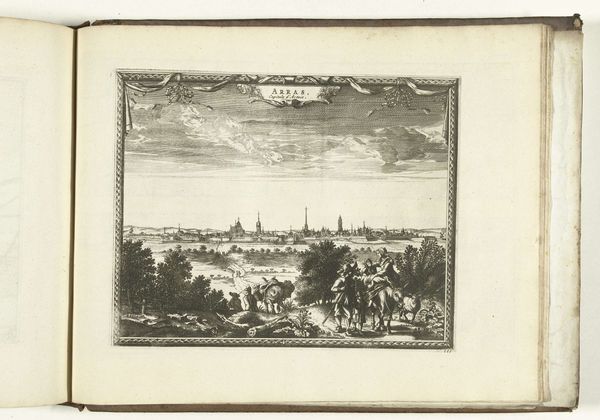

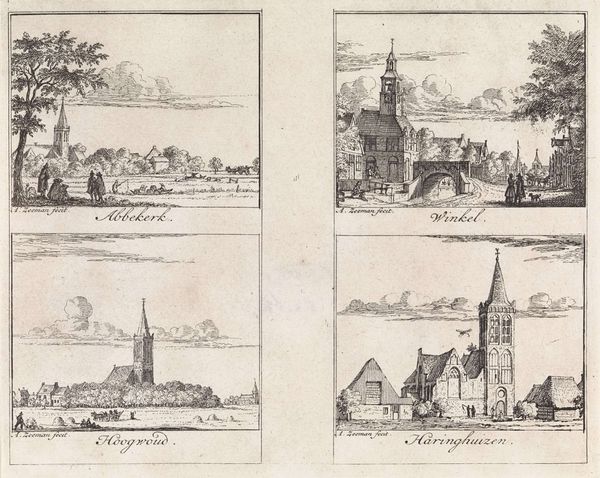

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

landscape

#

perspective

#

line

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 145 mm, width 87 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

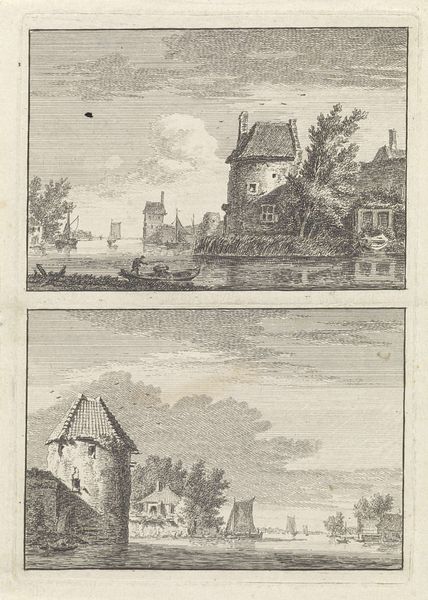

Curator: Welcome to this display of 18th-century Dutch printmaking. We are looking at "Gezichten op Leerdam en Vianen," which translates to "Views of Leerdam and Vianen," created around 1730 by Abraham Zeeman. It's an engraving showcasing these two towns in separate registers, one above the other. Editor: My first impression is one of serenity. There’s a gentle stillness despite the bustling scenes of these waterfront towns, like time captured and held delicately in each tiny line. Curator: That feeling, I think, comes from the era. The Dutch Golden Age was over, but the need to display civic pride in commerce and society never really died out. Note the specific buildings Zeeman decided to showcase; it offers a snapshot of power and control in these townships. Editor: I agree; look at how he's meticulously rendered the architecture—each steeple and rooftop asserting dominance on the skyline. But also note the water: it speaks volumes about connection and exchange, a symbol deeply embedded in our collective history. I mean, isn't it interesting to think about the psychological comfort derived from this familiar and safe imagery in the Dutch psyche at the time? Curator: Definitely, but the reality for the common person might have been more precarious. The prints would circulate in albums of wealthy patrons and emphasize that comfort—though it would be a skewed reality for some. In which ways did the average merchant interact or associate with these iconic landscapes, versus how the Landed Gentry perceived them? What might they leave out? What narrative might they suppress or choose not to remember? Editor: And I guess the visual language solidifies that, right? We recognize the symbols - churches, windmills - the infrastructure which builds on Dutch identity. The towering cumulus clouds almost take on allegorical value - these cities are safe; protected from a world of changing weather and political conflict. But, as you say, is that an enforced reading of national peace? What were the socio-economic situations for inhabitants living inside the illustrated walls? Curator: Exactly. Thinking about art's role within historical, socio-political, and identity discourse opens avenues for challenging narratives and confronting historical elisions. It's essential not just to look, but to ask what isn’t so plainly displayed. Editor: Absolutely, it is a reminder to consider both image and icon. It’s a deceptively simple presentation of pride and place that, on further inspection, has an underlying current of political narrative at play. Curator: Thank you for joining me on that journey, looking beyond the immediately apparent. Editor: Indeed, seeing how those historical elements can still stir the waters of the present, so to speak, has given a greater resonance.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.