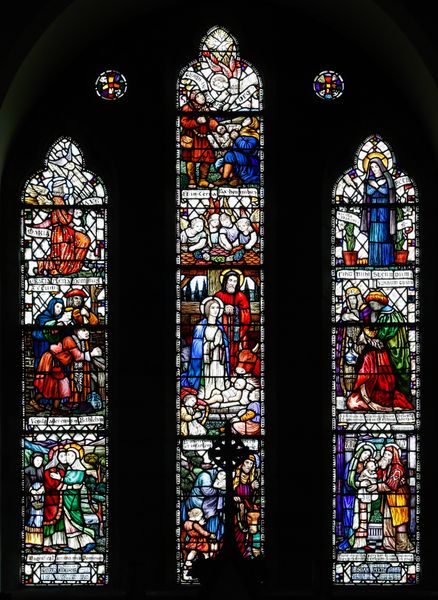

King Cormac of Cashel as Bishop, Warrior and Scribe. St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin (detail) 1906

0:00

0:00

glass

#

portrait

#

medieval

#

figuration

#

glass

#

history-painting

#

decorative-art

Copyright: Public domain

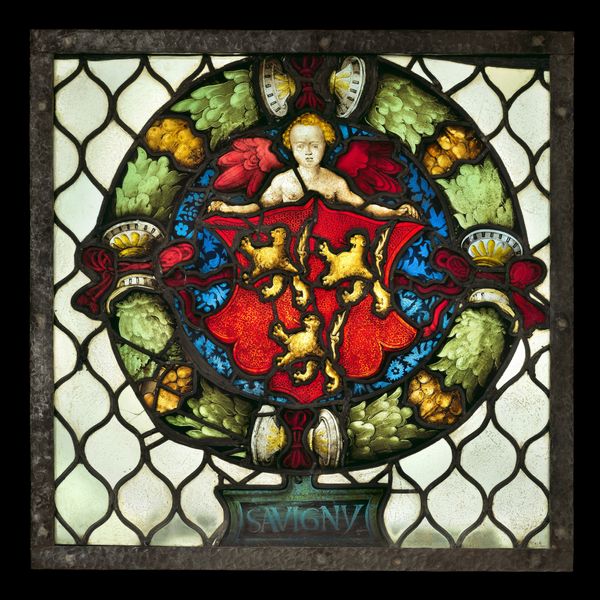

Curator: This stained-glass panel, created by Sarah Purser around 1906, captures King Cormac of Cashel in a rather unique light. It’s part of a larger window at St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin, showing him as a bishop, warrior, and scribe all in one. Editor: The first impression is somber. Look at that angel, burdened, embracing what appears to be the royal coat of arms. Is it mourning or protective, or perhaps a bit of both? The overall mood feels melancholic, and it strikes me as quite interesting in relation to stained glass typically designed to convey hope. Curator: I think that melancholic mood is so palpable because, unlike a glorifying depiction, it appears like this angel is *struggling* to lift this heavy shield – that is, the royal emblem. It feels intensely symbolic – perhaps referencing Ireland itself in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The inscription commemorates soldiers who died in South Africa, intertwining themes of faith, Irish identity, and colonial conflict. It's worth noting the visual style is inspired by medieval illuminated manuscripts—something that lends to the atmosphere, and in a material form so appropriate to a cathedral. Editor: Absolutely. You can see the Pre-Raphaelite influence in that detail. It also reflects the complexities of Irish nationalism at the time. Remember, many Irishmen fought for the British Empire. Placing the panel within this specific historical context allows us to discuss the problematic dynamics of sacrifice, belonging, and memorialisation, doesn't it? How the national and religious narratives intertwined – especially given King Cormac as a figure. Curator: It's also fascinating to think about Purser's role as a female artist engaging with such potent nationalistic and historical subjects. You rarely see stained glass discussed with such socio-political undercurrents. It shifts the whole reading. Editor: Exactly! Her choice to portray this almost defeated guardianship opens a space to critically consider the idealized narratives of both Irish and British imperial history. In a strange, sorrowful way, there’s a lot of emotional, historic honesty here.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.