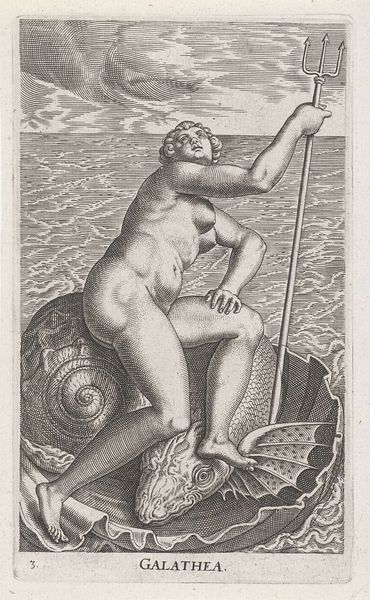

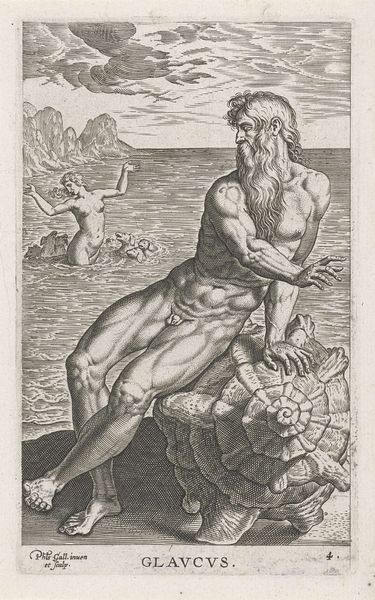

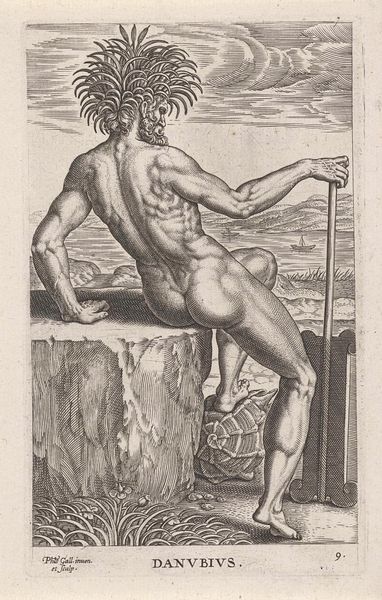

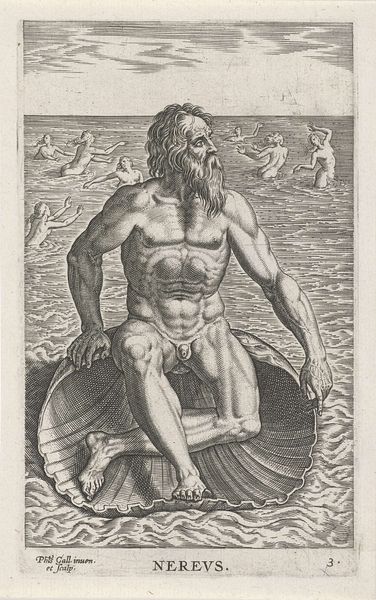

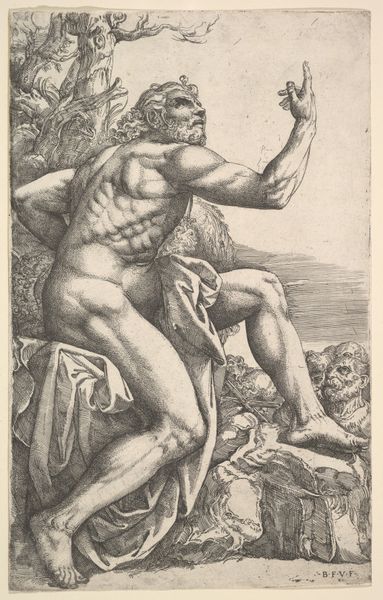

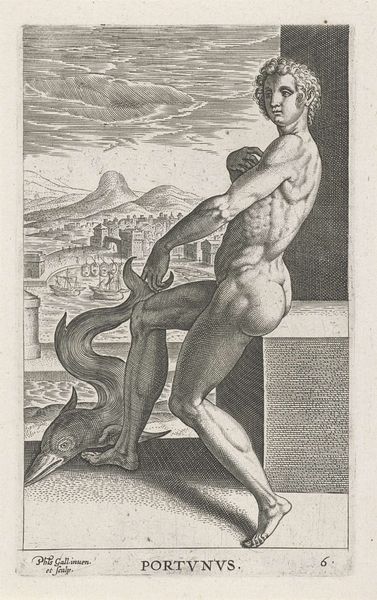

Dimensions: height 165 mm, width 102 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

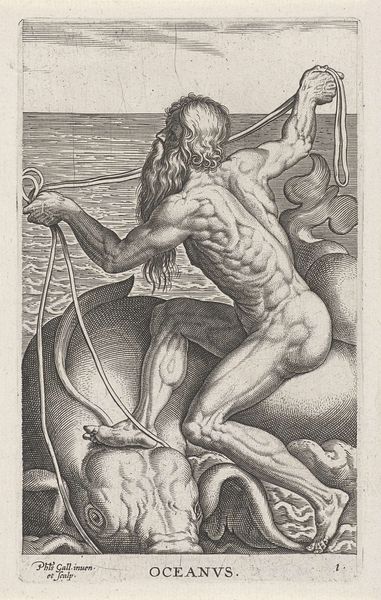

Curator: Here at the Rijksmuseum, we have "Zeegod Neptunus", or "Sea God Neptune," an engraving created by Philips Galle in 1586. It presents the Roman God of the Sea. What is your initial impression? Editor: I am struck by how much emphasis is placed on the figure’s body – its muscularity, the curves. It feels rather exposed and…powerfully presented for an allegorical print. It also strikes me that Neptune is sitting on what appears to be a globe; he truly commands the seas, doesn't he? Curator: Galle’s masterful skill with engraving techniques is what captivates me here. Notice the detailed lines that define the anatomy, almost hyper-realistic. The way he crafts light and shadow simply with those etched lines...and alludes to the consumption of art among wealthy patrons who prized refined and skillfully produced images. It shows how art production intertwines with systems of power and resources. Editor: I agree, the meticulous detail really showcases Galle’s artistry, but it also served a larger social function, didn’t it? Prints like these disseminated classical imagery and stories, shaping cultural understandings and promoting certain ideals among the elite and learned classes. Think about how it places Neptune in the center as if to imply that nature itself is at man's disposal, if the man is in line with values deemed appropriate. The pose itself is telling: He appears in a moment of thoughtful stillness more than a god of action, like a noble reflecting on his role in society. Curator: The tools used in its making speak to me as well: the burin, the metal plates... it's a very direct, almost industrial method. Each line bears witness to the hand that carved it and to the printing press that multiplied it. We forget the sheer labor embedded in these early prints when we see them presented so simply on a wall, far removed from the workshop realities! Editor: It’s true. This wasn't just about Galle’s talent; it reflects the broader organization of labor in printmaking workshops. Who was doing what? How did the division of labor affect the image and its reach? But looking beyond the studio, it also prompts consideration for what images like this represented. How did it circulate and influence the values and understandings of its viewers during the 16th century? Curator: Exactly, examining the material nature alongside the social context adds so much to our experience. Editor: A welcome complement that allows us a fuller consideration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.